Who is winning the 'crypto-war'?

- Published

In the war over encryption between the NSA and privacy activists, who is winning?

Ladar Levison sits exhausted, slumped on a sofa with his dog Princess on his lap. He is surrounded by boxes after he moved into a new house in the suburbs of Dallas, Texas, the previous day.

He describes his new home as a "monastery for programmers". Levison and co-workers plan to live and work there as they create a new email service which will allow people to communicate entirely securely and privately. His goal, he says, is to "spread encryption to the masses".

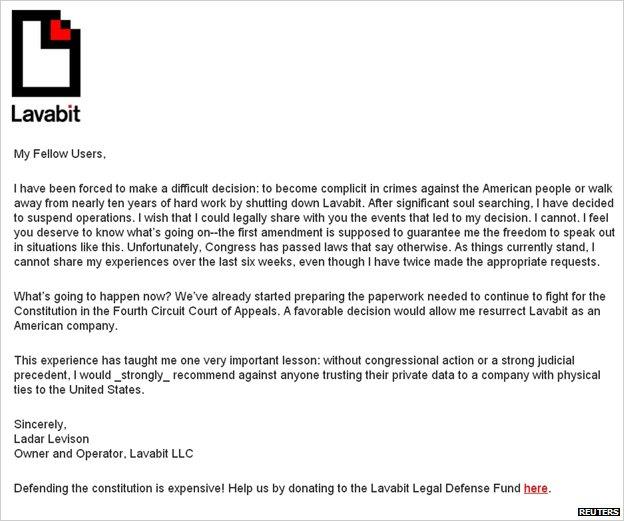

It is a new email service because Levison himself shut down his old one - called Lavabit - after a visit from the FBI.

It began with a business card in May of last year. They were after the communications of one of his clients. Levison cannot say who it was but everyone knows it was Edward Snowden who had just left the country with a stash of secret documents and was using his Lavabit email to communicate.

A tussle with the FBI led to a court ordering Levison to hand over the keys to his email service. He feared it would leave all his 400,000 users vulnerable so he came up with a plan. The keys consisted of thousands of seemingly random characters. Rather than hand them over in electronic form, he printed them out. In tiny type. And then handed over the piece of paper.

"I met the FBI agents in the lobby and I handed them the envelope and the FBI agent held it up to the light, wiggled it back and forth and was like 'Are these the keys?' And I said yeah. I just printed them out. He was like 'Oh'. So he wrote out a receipt for one sealed white envelope."

Levison knew that it would take time for the FBI to input the keys and that gave him the chance to shut down his entire system. He had named his machines after his ex-girlfriends and describes the process of pulling the plug as a "surreal experience… seeing all of the lights continue to blink out in the ether as all the users tried to continue to access their email even though the systems had been turned off."

At the heart of Ladar Levison's case is a question. Do we want our communications to be entirely private so that absolutely no-one apart from the recipient can know what's being said? Or are we prepared to allow the state access - for instance when it says it is investigating crime or protecting national security? That issue has come to the forefront now because of Edward Snowden. But what's known as the crypto-wars have in fact been going on for 40 years.

You could date the start to a meeting at Stanford University in California in 1976. On one side of the table were a pair of mathematicians - Martin Hellman and Whit Diffie. On the other were a team from the federal government - including the NSA.

Hellman and Diffie believed that a proposed federal standard to encrypt data had been deliberately weakened by NSA to allow its supercomputers to break into communications. There had also been suspicions of so-called back doors which would allow the NSA secret access. In an increasingly heated exchange the two sides argued over how much computing power would be needed to break the proposed standard. "My view at the time was that I was Luke Skywalker in Star Wars," Hellman tells me in his home on the sprawling Stanford Campus, "and NSA was Darth Vadar."

Soon after that meeting, Diffie and Hellman revolutionised the world of codes by publishing a paper outlining a concept known as "public key cryptography". Until then the process of encrypting information was something only governments did, but public key offered the chance for ordinary people to be able to communicate securely.

Adm Bobby Ray Inman took over as NSA director in 1977. He found his staff worried by the intrusion into what had been their domain. "The great worry was that this effort would produce cryptographic systems that they couldn't break and it wasn't just worry about drug dealers and the rest of that," he told me in his office in Austin Texas. "It was that they could be picked up by foreign countries." Inman decided the two sides needed to talk and went to see Hellmann, which led to a dialogue between the NSA and the academic community.

But encryption was spreading. Commercial companies began developing products they wanted to sell - and export. And activists began building systems for people to use - the most significant being Phil Zimmermann, whose PGP encryption programme ended up being distributed for free over the early internet. The FBI and NSA began to worry. "It turns out that the biggest, most enthusiastic market for strong encryption are people who have a lot to hide," says Stewart Baker who took over as NSA's top lawyer in 1992 and who cites criminals, including paedophiles, as well as foreign spies as those who used the new systems. Those opposing the NSA argue though that these concerns should not trump the public's right to privacy.

But by the end of the 1990s, encryption was out there and the crypto-wars looked to have been won. At least that is how it seemed at the time.

At the annual RSA Security Conference in San Francisco a few weeks ago attendees got to choose a film to eat their popcorn in front of on cinema night. They picked Enemy of the State, a Will Smith thriller featuring rogue agents from the NSA.

Edward Snowden has become an enemy of the state but to many privacy activists, it is the state - and specifically the NSA - which is the enemy.

The issues raised by Snowden - especially the claim that the NSA had worked to defeat encryption - hang over the meeting. A session on random number generators turns into a discussion as to whether the generators have been rigged by the NSA to provide a backdoor.

"The government lost the crypto-wars," leading cryptographer and NSA critic Bruce Schneier explains in the margins of RSA. "Crypto is now freely available but in a sense they won because there are so many ways at people's data that bypass the cryptography.

"What we're learning from the Snowden documents is not that the NSA and GCHQ can break cryptography but that they can very often render it irrelevant… They exploit bad implementations, bugs in hardware and software, default keys, weak keys, or they go in and break systems and steal data."

The National Security Agency's data Centre in Utah

The NSA has long shrouded itself in secrecy. But in recent months it has realised it needs to fight its corner. I was allowed into its headquarters in Fort Meade, Maryland, for an overview of its work - but without any recording devices. In a downtown Washington hotel though, I did speak to Chris Inglis, who stepped down as deputy director of the NSA. He is a man who is careful with his words but his anger at Edward Snowden's revelations lie just beneath the surface. "There's a sense of betrayal that someone appointed himself judge and jury," he says, adding that America's adversaries will now have a "greater sense" how to avoid the NSA's attention.

He argues that "NSA does not have backdoors into the world's encryption writ large".

The NSA's "principal forte" he says "is trying to find those things that are either inherent, accidental or merely the slips and pratfalls of people who don't implement these things properly."

As to the claim that vulnerabilities are inserted into commercial systems to make them exploitable, Inglis does not deny the possibility but suggests such techniques would only be used selectively. "Any activity of that sort would then in my view be focused on a very specific target - probably tactically focused and only for those legitimate purposes." The NSA has defensive and offensive roles - with securing national security information as well as stealing that of others - but the tension between these roles has been highlighted by the increasingly widespread use of commercial cryptography, including by the government itself.

Encryption is invisible but it is everywhere today. Every time you bank or buy something online, when you make a call on your mobile or when your key fob opens your car. Crypto may be out there. But the crypto-wars - the battle between those who believe privacy is king, and those who support the state's right to listen in - are only going to grow fiercer.

Listen to Gordon Corera's report on Crypto-wars on BBC Radio 4 on Sunday 16 March at 13:30 GMT or catch up afterwards on iPlayer

Follow @BBCNewsMagazine, external on Twitter and on Facebook, external