Louis Theroux: Moving to Los Angeles

- Published

For his new series of documentaries about Los Angeles, Louis Theroux and his family relocated to the city, where they found themselves gradually embracing the Angeleno way of life.

Late in 2012, having grown temporarily tired of life in dark and rainy west London, I moved with my family to sun-kissed Los Angeles, land of freeways, palm trees, beaches and celebrity.

We wanted an adventure. My children were young enough to be open to the idea of a big move - or, more likely, too young to understand what they were signing on for. My wife, raised abroad in sunnier climes, craved a break from another British winter. As for me, a professional observer of American culture in all its glory and absurdity, I reasoned it could only be a good thing for my work if I lived in the midst of the strange tribe I was studying, in classical anthropological style.

The alleged negatives of Los Angeles are well known. You have to drive everywhere. The city is a big, ugly sprawl. The people are shallow and obsessed with appearances. Everyone is either in The Industry or trying to get into The Industry. It's "faddy" - there is always a new ludicrous self-help regimen which involves drinking "kale smoothies" while "soul cycling", then spending the afternoon in your dojo studying the Kabbalah and getting a butt-wax.

But the shallow, trendy side of LA in a way is part of its appeal. That's what LA is for - to celebrate the shiny surfaces of life, to be a counterpoint to the excessive self-effacement and reserve and sense of tradition of the British. In theory, isn't that why so many Brits go to live in LA? Not just for the sun but for the sense of un-selfconsciousness and the chance of self-reinvention.

My wife and I found a house on the east side of Los Angeles, in a pleasant tree-lined area called Los Feliz. Our children enrolled in a local school and we started our new lives as Angelenos. The BBC rented a small office on a Hollywood lot, built aeons ago (in LA years) by Charlie Chaplin. We did our best to acclimatise (or "acclimate"), but slowly. We sourced local outlets that stocked PG Tips. We had Alpen and Soreen flown in by visitors.

We bought a second-hand car, becoming, rather freakishly in LA terms, a one-car family. I cycled into work, taking my life in my hands as LA drivers zoomed past me, texting, checking email, applying make-up, making their lunch.

Labouring with my small production team, alongside the ghost of Charlie Chaplin, we began to evolve the idea of multi-part series set in Los Angeles - not so much about the city, but osmotically of it. Los Angeles would be a backdrop, infusing it with its own irresistible LA-ness, but we would not be making documentaries about Hollywood glamour, showbiz agents and publicists, parties, premieres. No, the programmes would be our kinds of stories - immersive examinations of life at its most raw and emotional, explorations of crime, mental illness, life and death, but unfolding in this sprawling megalopolis, which embodies all the best and some of the worst of life at the beginning of the 21st Century.

Back in England, I'd been reading about the peculiarities of the US healthcare system and the strange paradox of its end-of-life spending - that patients and doctors sometimes feel an obligation to keep going at any cost, even where the treatment is painful and the benefits highly speculative. Doctors, for understandable reasons, like to offer solutions and look on the bright side, even when reality has other plans. Massive amounts are spent on interventions that are (arguably) of questionable benefit. Patients are - in some cases - robbed of the chance of spending their final moments at home comfortably among friends and family, and instead die hooked up to machines in a sterile room.

Not exactly a feel-good story, but the hope was that the drama of the decisions being taken - of whether to accept an ultra-long-shot treatment or coast gently onto the off-ramp from life's freeway - would make up for the potential bleakness of the subject.

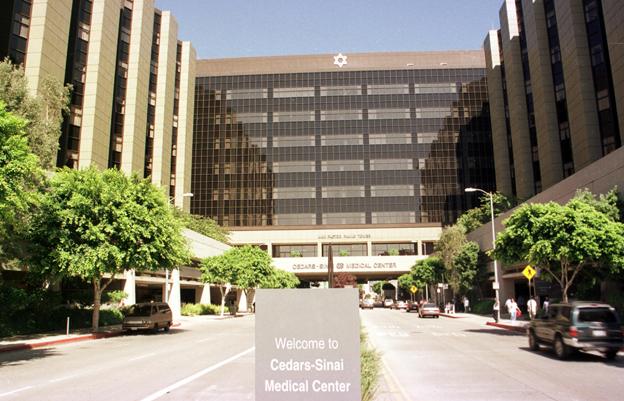

Cedars-Sinai Medical Center allowed us in and we filmed over the course of several months. Cedars-Sinai is sometimes characterised as the favourite hospital of the glitterati. But it also caters to normal civilians. The experience of being among people facing the most awful decisions of their lives was as harrowing as you might expect. But as odd as it sounds, it was also, at times, life-affirming - seeing the unstinting support from families, the dedicated care of the doctors, and forming a connection with people going through the darkest of times.

It became clear that, because we were based in LA, we could be present for moments of actuality that we would have missed had we been working from London. The results are evident in the film, in the quality and power of the scenes.

Conscious that, powerful as it was, what we'd filmed so far was a little on the sad side, we made an effort to lighten things with our second documentary for the series. I became interested in Los Angeles' dog lovers - the lives of the pampered pooches and anthropomorphised Beverly Hills chihuahuas, and also the grittier world of pitbulls and weaponised "bully breeds" in the high-crime areas of south Los Angeles.

In Los Angeles the division between rich and poor is reflected in an even more extreme way in its canine population. Where haute bourgeois pets can expect the best of everything - custom-made doggy hamburgers, rooms at doggy hotels, grooming and even plastic surgery - large numbers of the dogs of south Los Angeles are neglected and abused. Many are street dogs, roaming free in packs, committing mayhem. Among American cities, LA has one of the worst problems of stray dogs. In the low-income area of south LA the city shelter euthanises thousands of unwanted dogs every year, a disproportionate number of them pitbulls.

But perhaps most intriguing is the social mobility of these dogs. Many of the pampered dogs are "rescues". They are taken out of shelters, adopted, My Fair Lady-style, and taught how to behave in polite society. These dogs are given new homes, new names, new lives - but all of it is contingent on their ability to learn, well, new tricks. Their failure to do so - an inability to drop their old hood habits - can mean a one-way trip to the vet.

And so the dogs film became a film about that old Hollywood staple - reinvention and its limitations.

Filming on both stories proceeded with the rhythm of LA traffic - passages of maddeningly slow progress gave way to stretches of open road. In the meanwhile, I grew used to the pleasures and frustrations of the city. I loved being able to film and at the end of the day, go home - not to a hotel in a foreign country but to my family. I loved seeing the pool swimming and boogie-boarding at the beach. The children picked up situational American accents that they used with their friends but not with us.

But the city took its toll. I gave up cycling to work. It was too scary sharing the road, on the way home, with distracted drivers going 50mph in the dark. I adopted the LA practice of cycling simply for pleasure - "going biking". (In the same way as Angelenos don't walk anywhere but love to "hike".) After a couple of not-so-great experiences with bus journeys across the city, I caved in and rented a second car. It was faintly heartbreaking to recognise the city had foiled my best intentions. We became one of those families that drive round the corner to buy a pint of milk. Very occasionally, when I met my wife and kids out somewhere, we would drive home in an absurd one-family motorcade.

The glamorous side of life was occasionally in evidence. Through tenuous connections to the world of showbusiness, I found myself at one or two A-list parties and had the ambiguous pleasure of watching a top actor's eyes glaze over as I mentioned that I "made documentaries for the BBC".

I was also pleased to attend a local dinner party at which one guest announced his self-imposed dietary restriction - that he wasn't a full vegetarian but he only ate meat when he was outdoors and another mentioned she only ate meat after 6pm. If anything it was nice to confirm that the randomness of LA lifestyle choices is alive and well.

At work, the subject of the third and final episode of our LA series proved tricky to nail down. Then I stumbled across a newspaper article about a park that was breaking ground in south LA. Though it was hoped it would be used by children, the park's primary purpose was to drive out sex offenders from the area. Across California, there are laws preventing registered sex offenders from living close to places where children congregate, and so the park would, in theory, render swathes of housing out of bounds to them.

This story led us into an exploration of the dark world of Los Angeles paroled sex offenders - their troubled histories, the atmosphere of fear and suspicion that surrounds them, and the difficult tension most of us feel between the urge to punish and monitor these people and the impulse to rehabilitate and reform.

It was a difficult few months of filming. The sex offenders were at best ambiguous figures and at worst chaotic and dangerous. More than once I remember feeling nostalgic for the less complicated emotions of sadness and loss on the cancer wards. And yet, for all its ugliness, and maybe partly because of it, it became clear over time that the sex offenders story would make for a compelling documentary, following my stumbling attempts to find a way through the moral maze of how we should treat and what we owe some of society's most hated and most feared people.

I am feeling a little trepidation about returning to London to do some promotion, worrying that it will be cold and rainy and that I'll have to walk and be among other people without reassuring glass and metal of my car to insulate me. As I type this, I am sitting in a Starbucks on Hollywood Boulevard. Like most coffee shops in LA, it is suspiciously full, catering to that over-subscribed Angeleno specimen - the person who doesn't have anything to do in the day. We are a five-minute walk from my house but I drove here.

I think I may be adjusting to life in Los Angeles rather too well.

The first episode of Louis Theroux's LA Stories, City of Dogs, is broadcast at 21:00 GMT on 23 March on BBC Two - or catch up on BBC iPlayer

Follow @BBCNewsMagazine, external on Twitter and on Facebook, external