Malaysia plane: How do you mourn a missing person?

- Published

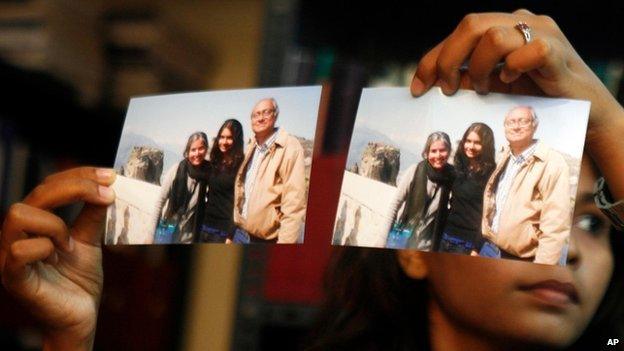

Daughter of passenger Chandrika Sharma shows family photo

The relatives of passengers on board the missing Malaysian Airlines plane have been told the plane crashed in the ocean, with no survivors. So how hard is it to mourn a missing person?

When flight MH370 went missing, Prahlad Shirsath travelled from his home in North Korea to Beijing and then on to Malaysia as he searched for news of his wife's whereabouts.

Kranti Shirsath, a former chemistry professor and mother of two, was travelling to see her husband who worked at a non-profit organisation in Pyongyang.

When there was no news and the days passed, Shirsath's family called him back to his home country of India, where they could endure the uncertainty together.

This is called an "ambiguous loss", says Pauline Boss, professor emeritus at the University of Minnesota, who treats people undergoing this unique kind of bereavement. There is no physical proof of death - no body - so people cling to the hope that the missing are still alive.

"People can't begin mourning when there is ambiguous loss - they're frozen," says Boss. "Frequently, society thinks they should be mourning but, in fact, they are stuck in limbo between thinking their loved one might come back and thinking they might not."

This is a kind of suffering that freezes their grief, says the professor, author of Ambiguous Loss: Learning to Live with Unresolved Grief.

The latest news that the plane probably crashed in the southern Indian Ocean, with no survivors, is unlikely to release them from this limbo, she says. "There is no closure even if they find definitely that the plane is in the ocean. They still have no body to bury. It will always be ambiguous until remains are found or DNA evidence."

People need to see evidence before they are assured that the death has occurred, says Professor Boss, and without that, grief is frozen and complicated. A more clear-cut death is undoubtedly painful but funeral rituals can take place where there is a body, and family and friends come together to re-affirm that the person has died.

In the absence of a confirmed explanation for what happened, relatives imagine their own outcomes. Before the latest news, Kranti's family, including her 16-year-old son, were inclined towards the one that offered most hope - that the plane was hijacked, a scenario in which it was more likely that Kranti was alive.

Banner with messages for missing passengers

"We don't really have the strength to entertain the possibility of any bad news at the moment," says Satish Shirsath, Prahlad's younger brother, speaking a few days ago. He was the one who booked Kranti's tickets online.

"I also feel that maybe if I had chosen another route - maybe if I had booked my sister-in-law from Pune instead of Bombay, then to Delhi and Beijing - perhaps it would have been different," he says.

When there is no knowledge of what happened, there is no one to attribute responsibility to, so blaming oneself is typical, says Boss. The first thing she tells families in therapy is that it is not their fault.

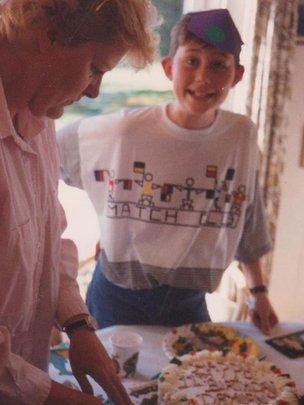

Damien Nettles, 11, five years before he disappeared

Catastrophic events like 9/11 and the Asian tsunami left many relatives and friends waiting in vain for definitive news, but this kind of loss can also happen when someone walks out the door and never comes back.

Valerie Nettles - whose son Damien went missing 17 years ago in the Isle of Wight when aged 16 - has learned to compartmentalise the pain.

She says she lives with one step in two different worlds - one in an "abyss of not knowing" and the other in the practicality of everyday life.

"I always thought that if something happened to my child, I would die - but you don't," she says.

Damien was last seen at a fish and chips shop near his house in Cowes, after a night out with friends. Several theories about what happened have come out since - some think he might have fallen into the sea and others, including his mother, believe he may have been murdered by drug dealers. In 2013, the police posted a £20,000 reward for anyone with information that would help solve the case.

Valerie remembers a vivid dream about her son, in which she saw him across a motorway with her husband and younger son.

"I was elated they had found him, but then I woke up," she says.

Dreams about loved ones are common for people whose relatives are missing. Sometimes, people even dream the ends of the incomplete stories of the missing person - that they are either dead and at peace or happy somewhere far away. Some cultures attach a lot of significance to these dreams, says Boss, and it helps people to cope better with the ambiguity.

Ambiguous loss is less difficult to negotiate if you live in a culture - for example, where religions such as Hinduism and Islam are dominant - that tend to "accept the fate that a higher power has delivered," Boss says.

"The more 'mastery-oriented' people are, the harder time they seem to have. Because you can't manage it, you can't master it, you have to live with not knowing and that is very hard for most of us to do."

Relatives of MH370 passengers were distraught at the latest news

Telling someone who has a missing relative to simply begin the mourning process is not helpful, she adds, because you cannot push those who are suffering in this way to accept any one scenario.

"My first question to the family is - what does this mean to you? And you get the answer and you can build on that," she says.

Nettles is closely following the developments of the missing plane from Texas, where she now lives. Having every detail played out so publicly must be a "rollercoaster" for the passengers' loved ones, she says.

"It tears you apart - all the 'what-ifs' and 'maybes'." Nettles still wrestles with having decided to relax Damien's curfew deadline the night he disappeared in 1996.

Seventeen years on she has tried to move on for her family but she says she is "limping through life".

"I'm still hoping for something - I don't know what," she says.

Follow @BBCNewsMagazine, external on Twitter and on Facebook, external