Cornelius Gurlitt: One lonely man and his hoard of stolen Nazi art

- Published

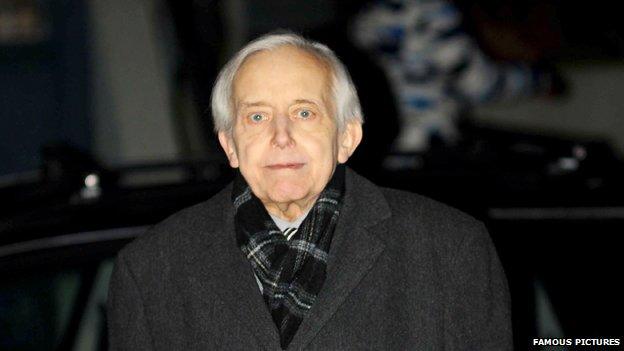

The BBC's Stephen Evans was granted exclusive access to look at some of the long-lost masterpieces in 2014

Cornelius Gurlitt hoarded more than 1,500 works of art, some stolen from Jews in Nazi Germany, for more than half a century. The BBC's Steve Evans was given exclusive access to the high-security storage depot where the 238 treasures he stored at one of his homes, in Austria, are now being held.

One day, no doubt, Hollywood will make a movie.

A reclusive man with his secret hoard of art. In the damp of his home, behind the shutters, spiders would crawl over masterpieces - until his secret was blown and his hidden trove uncovered.

Perhaps the script is already being written. It will be a crime movie, of course - some of these works were snatched from people who were being bundled away to be murdered.

It will be a mystery film, too - how did a sad and lonely man hide such a big collection of pictures for so long. Cornelius Gurlitt would sell a painting when he needed the money (just the odd few millions) - but didn't the wise and intelligent of the art world ask any questions? Or did they not want to ask for fear of the answer?

It will be a movie with some suspense. Cornelius Gurlitt was caught after he was stopped on a train travelling between his home in Germany and his bank in Switzerland. A customs official who boarded the carriage, searched him and discovered about 9,000 euros (£7,500), just below the legal limit for the transfer of cash out of the country but enough to raise suspicions and to prompt an investigation of the flat in Munich.

But how will Hollywood depict Cornelius Gurlitt himself? Is he a villain, or a tragic figure, compelled to shuttle secretly, with wads of cash, returning home to spend his life with inanimate works of art?

Perhaps, he's both.

The treasures were often pushed into corners among a mess of waste paper. Mould grew on some of the surfaces. The radiance of the paint has been dulled by a filter of dirt.

It's not that Cornelius Gurlitt didn't care about the paintings. Indeed, those who have talked to him say he thought of them as his friends. He would sit in the dark with them, his only companions on the planet once his parents and sister had died. Whether he talked to them, we do not know, but he seems to have communed with them in what must have been solitary, sad meetings behind the shutters of his flat in Munich and house in Salzburg.

The house in Salzburg (left) and the Munich flat where Gurlitt kept his collection

It's more that he couldn't cope. He certainly couldn't cope physically with the task of curating a collection which is comparable in number to that of many of the world's major galleries. The National Gallery in London, for example, has more than 2,000 works in its collection. Gurlitt's collection consisted of two-thirds that number - 1,280 works in his Munich apartment and 238 in his Salzburg house (of which 39 were oil paintings). The Gurlitt stash contains some masterpieces grand enough to get auctioneers salivating but also a lot of minor drawings and water-colours - but all required a care he couldn't give them.

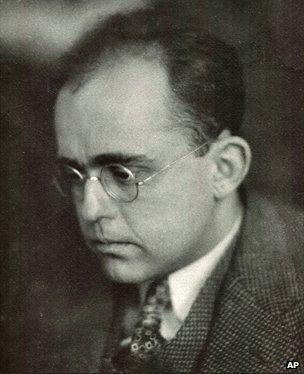

Gurlitt's father Hildebrand amassed the collection

He couldn't cope physically but he couldn't cope emotionally either. Cornelius Gurlitt was 24 when his father died in 1956. In the half century and more since, the son has lived under the burden of his father's instruction to preserve the collection built up in the 20s, 30s and 40s.

The father, Hildebrand, was then an art dealer who, despite a Jewish background, was approved by the Nazis to deal in works, some of which were either looted outright from Jewish families or bought under extreme duress from people preparing to flee for their lives.

The father died and the son had to cope with the legacy which was to be his security in old age but also a curse.

Cornelius Gurlitt is now recuperating from heart surgery as the lawyers swirl around him. The works are being pored over in secure warehouses by restorers and by experts trying to trace their history.

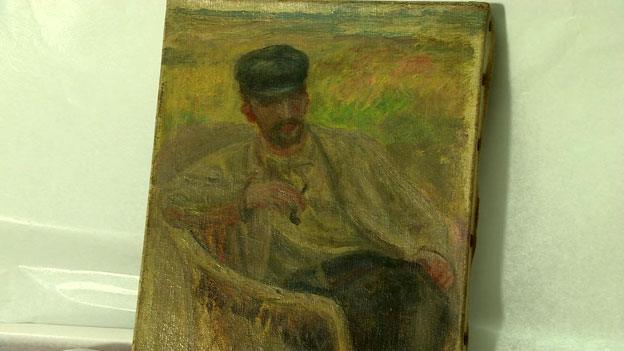

When you see them in their new environment with its regulated humidity, temperature and light, the effect is surprising - and strangely anti-climactic. The key turns on the thick metal door and in you go to be confronted by trestle-tables on which are works you immediately recognise as by Picasso, Renoir, Monet, Manet, Courbet and Cezanne - the style is there but the paintings don't shine like they would in a public gallery.

Cornelius Gurlitt's stash might fetch hundreds of millions of dollars at auction, but the impact doesn't match the price-tag. The paintings look like the bric-a-brac cleared from an old man's home - which is exactly what they are.

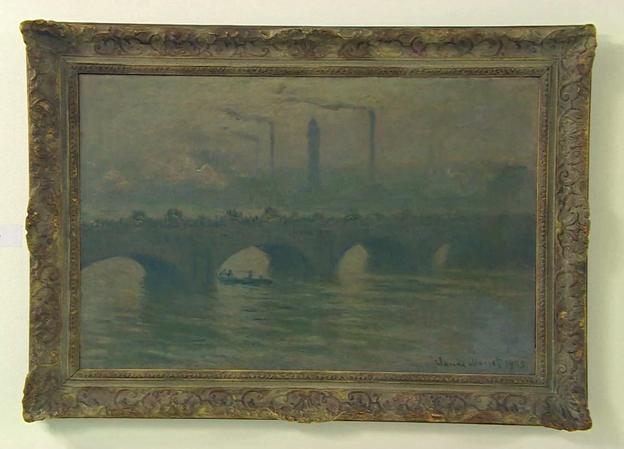

A Claude Monet painting of Waterloo Bridge (1903), seen in colour for the first time in 75 years

There, on the wall, is a Monet, one of his many depictions of Waterloo Bridge over the Thames in London. He produced many in what seems like an obsessive study of the London weather - some in the delightful series show the brightness of a Spring morning, others the fog of Autumn. When a few have recently come up for auction in New York, they have each fetched $8m or $9m (£4.8m or £5.4m).

This one from the Gurlitt trove seems to be in the deep gloom of winter - but it's hard to say because there is such a sheen of grime over it. It needs a good clean.

These paintings and sculptures fall into three categories.

Firstly, there are some works which were without doubt stolen. Gurlitt's lawyer, Stephan Holzinger, told the BBC that his client - whom he described as "a very shy person, a very discreet person" - had given instructions for these to be returned to the descendants of the original owners.

Secondly, there are works bought legitimately by Cornelius Gurlitt's father in unforced sales, either after the war or before the Nazis came to power.

And, thirdly and most contentiously, there are paintings accrued by Gurlitt's father during the war. This third group is the stuff of dispute.

A beach scene by German impressionist Max Liebermann

Pierre-Auguste Renoir - Man seated

Jean Desire Gustave Courbet - Full standing figure of a man

Edouard Manet - Seascape with two sailing boats

In regard to these paintings, the law will move slowly. Firstly, Gurlitt kept his paintings in two sites, one in Austria and the other in Germany, so the law of two different lands applies. On top of that, German law puts a limit of 30 years on claims by the descendants of those from whom art was stolen to make themselves known - and that deadline has passed.

The paintings were held in secret for far more than 30 years so how could anyone have claimed them?

Deidre Berger of the Ramer Institute for German-Jewish Relations says the trove shows that there's a very large chapter of the Holocaust that hasn't been fully addressed.

"As we are seeing with this unravelling story and the large amount of looted art which seems to be involved there's not a lot of good laws available to help people to regain their stolen art," she says.

"The reality is that it's very difficult to find the owners of most of these pieces of art. The survivors were children at the time. How should they remember precisely what a painting looked like hanging in their living room 70 years ago?"

But every piece of art which is returned to its original owners, she says, is a victory against the Hitler era.

Follow @BBCNewsMagazine, external on Twitter and on Facebook, external