How the secret police tracked my childhood

- Published

Fighting the system used to be dangerous anywhere in Eastern Europe. For one protester from a small Romanian village it was disastrous - and also for his family, whose every word was recorded by the secret police. Carmen Bugan, who found the transcript of her childhood, tells their story.

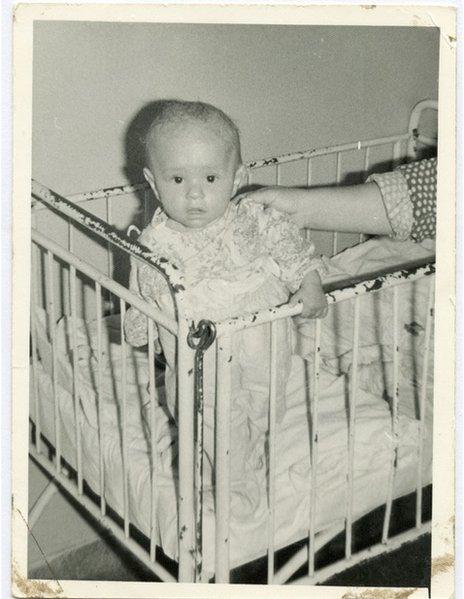

Soon after my brother's birth in February 1983 my father, Ion Bugan, was faced with the biggest decision he ever had to make.

Should he and my mother continue secretly typing anti-communist manifestos on an illegally-owned typewriter and distributing them around Romania? Or should he go to Bucharest to take on Ceausescu all by himself, without telling anyone a word about it?

Thirty years on we still live with the legacy of my father's choice. And with the discovery of an intimate, horrifying story of our lives written by the secret police, the Securitate.

This was a Romania of food shortages, frequent power cuts, and ferocious reprisals for any form of dissent. The sounds of forbidden US radio stations - Voice of America and Radio Free Europe - woke us up and put us to bed every day, sending shivers up our spines as they merged with the noise from the kitchen. They gave my father hope that life could be better if only people stood up for themselves.

The Securitate was well acquainted with my parents. In early 1961 my father was in a bar with his best friend Petrica and a few others complaining about high tax rates and the collectivisation of farms. They came up with a plan to hijack an internal flight from Arad, in the west of Romania, and to fly it out of the country.

Petrica was a retired air force officer who in civilian life repaired radios like my dad. They had no idea that one of their friends was a Securitate informer.

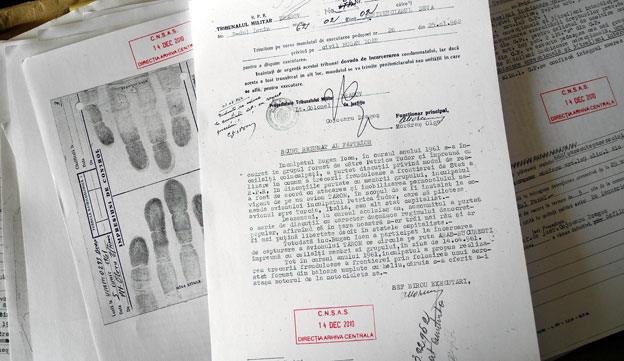

All were captured before they had a chance to take control of the plane and condemned to eight years of hard labour "for preparatory actions leading to fraudulent crossing of the border" (leaving the country without permission was illegal) and "plotting against public order".

My father, in his 20s, found himself in terrible prisons at Jilava and Deva and at the Great Island of Braila labour camp, where he met some of the political dissidents who were systematically tortured there.

Ion wore 45kg of chains in Jilava prison

In July 1964, my father and his friends were liberated in a general amnesty but the Securitate followed his every move, looking for any reason to discredit him and throw him back in prison. Suffocated and intimidated, in February 1965 dad bought a compass, binoculars, antibiotics, a few vials of caffeine, some cans of sardines, and a roll of salami. He and Petrica made a heart-stopping escape from Romania in a blizzard. Dodging police and hiding in haystacks, they made it all the way to the Iron Curtain at the Bulgarian-Turkish border.

On 2 March 1965 at 07:30 in the morning, starved, weak and frozen, they rolled down a hill, jumped a 2m-high barbed-wire fence and nearly crossed into Turkey. The patrol squad showered them with bullets in no-man's land, just 400m from freedom, and sent them back to Romania. My father was sentenced to 11 years at the harshest prison of all, Aiud, for "fraudulent crossing of the border, punishable with art. 267 of the penal code".

Part of the sentence was a five-month period of torture by solitary confinement and starvation while wearing 45kg of chains day and night, in the "special" wing of the prison at Alba Iulia. The prison records say he was transferred to Alba Iulia "for judicial affairs" which is true in a sense: my father was tortured there in order to "admit" his supposed role as an "accomplice" in the theft of money that had "disappeared" from his radio repair shop after he ran away to Bulgaria. My father's own account of this period is hair-raising: he was fed once every two days, and allowed to wash three times in the entire period he was held there.

But, as dad puts it, there was an angel looking after him - he was transferred back to Aiud and freed in January 1969 as a result of changes to the penal code.

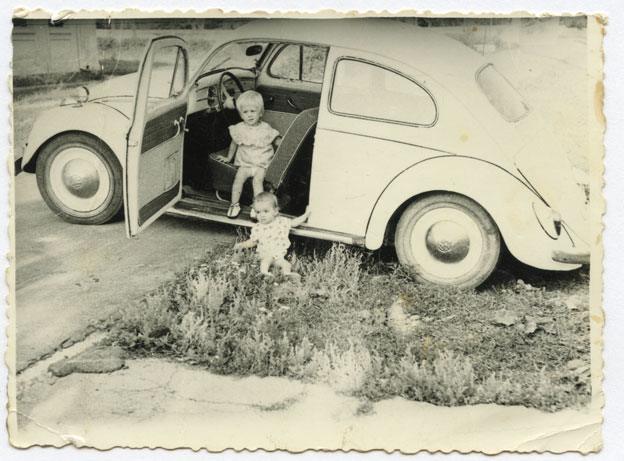

Dad now attempted to live a normal life. He married and had children. Things didn't seem so bad on the surface. We had summer holidays on the Black Sea and built a lovely house in our village, Draganesti, near Galati, in eastern Romania.

Loredana with father Ion

But behind the scenes the Securitate pushed him to breaking point, following and spying on him. My mother, Mioara, was denied a career in teaching because she married a "political agitator" and was therefore likely to "pollute the minds of the younger generation". Told to choose between job and husband, she opted for the marriage, and they both began working in a grocer's shop. Before long, mum was running the shop, and as dad had been banned from keeping the books at his TV/radio repair workshop, she did that too. Dad worked on repairs when he wasn't stacking shelves. My parents put up with their lot, and worked hard.

By 1981, however, there were not many groceries to sell. Hungry factory workers yelled at them: "What am I going to put in my bag for lunch?" Evening bread queues often ended in fist fights. When the doors closed for the day, my father's angry outbursts at the back of the shop mingled with blasts of Radio Free Europe. One day he told my mother: "I don't want to spend my life just breathing air, and doing nothing."

They bought two typewriters, one of which they did not register with the police, and began making anti-communist flyers protesting against shortages and human rights abuses. They spent the nights typing and driving all over the country to put them in people's letterboxes, while my sister and I slept. The police kept coming to the house to check the prints of the legal typewriter, and to see whether they matched with the letters.

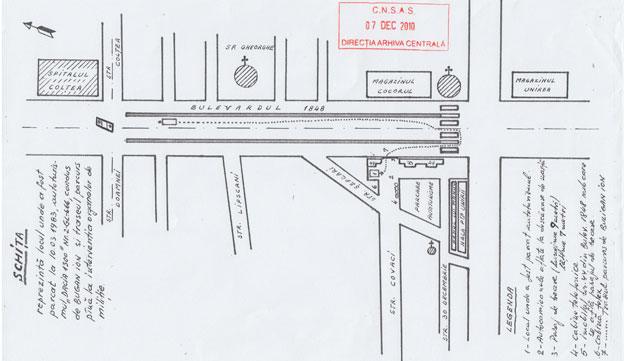

On 10 March 1983, about a month after my father and I visited the hospital with a bouquet of carnations to see my new-born brother, Catalin, my father took to the streets of Bucharest. On top of our red Dacia car, he mounted placards demanding human rights, and denouncing Ceausescu as a torturer who should be put on trial. Then he drove through the city centre, throwing leaflets from the window and blowing a whistle to attract attention.

The spies drew a map of Bugan's protest drive through Bucharest

He had said nothing to my mother. She was in the hospital with Catalin, who was close to dying from an untreated lung infection. My younger sister Loredana was away at gymnastics school and I was at home, aged 12, with my grandmother. This marked the beginning of hell for us.

Catalin was born a few weeks before Ion's protest

Dad's protest landed him back in Aiud, condemned to 10 years of hard labour for "propaganda against the socialist regime", punishable under art. 166 line 2 of the penal code. My mother, my sister, my brother and I were placed under close surveillance.

We became accustomed to travelling across the country for a yearly prison visit, letters sent but not always received, food packages returned to us because "the prisoner did not behave appropriately". Rotten fried chicken, softened apples and ulcer medication were sent back in the battered cardboard boxes in which we had placed them months before, hoping he'd receive them.

The Securitate had their own keys to our house and ordered us not to pull the curtains in the kitchen to make it easier for them to observe us. We later learned that my father had accumulated the codenames Andronic, Butnaru, Cazul Cocor, and Barbu, while Mum was codenamed Bela and Barbu. A school friend codenamed Cornelia was in charge of keeping a record of my feelings about dad for the Securitate.

In 1985 mum and dad were forced to divorce. By 1987 I had become accustomed to children at school, and one of the teachers, referring to me and my sister as "the criminal's daughters".

On his birthday in 1988, Ceausescu proclaimed a general amnesty. My mother quipped that history would remember him for his compassion - having no idea that we would find her words transcribed 30 years later in government archives.

When my father walked home in the night on 5 February 1988, secret microphones in the house "registered an atmosphere of joy coming from the children". My father "visited each room", "asked for his shaver" and looked "for his radio". He cradled Catalin in his arms, they noted. The transcripts of that first night say that "the family went to sleep at 03:45 in the morning. The Obj. [my father] complained of a pain in his heart."

The Securitate kept thousands of files on the Bugans

None of us remember all of these details, they are a gift from the record-keeping Securitate, but I recall the smell of prison on dad's clothes.

A couple of months after dad's return from prison, the secret police files note:

"At 01:32 in the morning, we could hear someone trying the door to the room equipped with listening devices. The door doesn't open. We hear the footsteps of someone walking away and the insistent barking of the dog as to a person who is a stranger to the house."

It is a transcript of the Securitate registering itself in the act of trying to come into the house to change the microphones. I read this file last August for the first time. It made me understand that when we heard noises in those years in Romania we weren't really crazy as we thought.

After receiving a series of invitations from mysterious men to meet them in town, death threats on the phone in the middle of the night, and even a call from a woman offering sex to dad, we decided to seek political asylum in the US. It was my turn to make a heart-stopping journey to the American Embassy with my father's prison papers to give testimony on behalf of the family.

I managed to get into the Consulate but I was promptly arrested on the way out and interrogated for 45 minutes. I kept repeating what I was told to say: "We are under American protection, you can't do anything to me." They let me go and told me to never go back there again.

The Securitate records show how "concerned" they were about us and what might happen, as immigrants, to our sense of Romanian identity. They tried to dissuade my mother from going to the US - they told her that life in the West was a form of slavery to rich, lazy capitalists.

We waited 11 months for our passports, under house arrest. One record says that "after we have used every method to discourage the obj. [this time Mum] from leaving, we decided to expel her from the Communist Party". It was, even according to the Securitate's own file, a humiliation ceremony, where her friends were forced to hurl insults at her.

"Your girls will become prostitutes," the passport clerk yelled at my parents. "Our hand is long," they said, turning to my father, threatening us with death if we spoke about what had been done to us once in America. I now read my mother's declaration in the files "not to damage the image of our socialist regime by actions or words", and wonder how she must have felt to leave the country in her 40s with three children, a husband who had returned from the heart of evil, and no idea where we were going.

As we made our way to Michigan at the end of 1989, each carrying one suitcase in which we packed a lifetime, the Berlin Wall tumbled down behind us. The bloody Romanian Revolution followed at Christmas time.

We arrived as political refugees in Grand Rapids, Michigan, on 17 November 1989, travelling via Rome, and landing at night, in a snowstorm, not speaking a word of English.

The Bugan family arrived in the US with no English

In a refugee centre in Rome we had been taught that Americans, when they ask "How are you?" don't really expect an answer; that they all have chequebooks; that they value democracy and free speech; and that all immigrants gain 8kg in the first year in the West because, well, there is just a lot of food to eat and most of it is rather different from our homemade soups. We couldn't have been more thrilled with all of that.

We became eager to "assimilate" into Western life.

My sister and I would often ask the people in Grand Rapids we knew best: "Do I look American yet?"

At the same time we saw on a donated television how the Ceausescus were executed. My father said: "This is all wrong, now the world will never find out from him about his abuses." My mother cried: "They are just two old people, they should not have been killed." And all of us danced in the living room with joy that a revolution was happening in Romania.

The uprising brought turmoil to the streets of Bucharest

I wondered if my father's protest might have played some role in bringing it about. My father wanted to return. We said firmly: "We are staying here, and you are not abandoning us yet again."

Twenty years have passed. We cleaned nursing homes, churches, worked at Burger King, made golf clubs, Mum worked in a children's clothing factory, and we went to school. My father collected all of the discarded televisions we found, fixed them, and we had a TV in each room: "Such a waste," he'd say.

We became American citizens. My sister and I married. She and her husband bought a house in the suburbs. We became "Romanians by birth".

In 1999 Romania opened the archives of the secret police to people who had been subjected to surveillance during the communist years.

My father said: "I know who I am. I don't need to know what the Securitate said about me." But I disagreed and managed to find our records in 2010.

Now, it was one thing to experience the Securitate following and threatening us. But it is another thing to read the complete record of our daily lives, including the traps neatly laid out for us, to lure us into committing an offence, which we escaped simply by instinct or luck.

Carmen reading the files made about her family's life

So, when my mother was in the hospital with my brother, the Securitate placed next to her a "patient" who also had a "sick child". Nurses and doctors helped to stage it all. The woman who became Mum's "friend" had a question scripted for her to help her spark the conversation. She produced reports on what mum said about my father and his dissidence.

Another example is a "legend" (a technical term used by the Securitate) by which an "Amnesty International employee" came to ask mum about my father and whether we were persecuted because of him. The officer was trained to have a German accent, and to look nervous. He invited her to a hotel in town to talk "out of the reach of the microphones".

This was a trap to throw my mother in prison for speaking with foreigners about my father. Again, we now have the official record against which we can test our own memory of that day when the man came to the house. After he left, my mother said: "No-one is this worried about us, I don't trust this stranger." It was a lack of trust that saved her.

There are records of dreams we recounted to each other in the mornings. The transcriber knew us so well, he or she was able to read and duly note our moods. Some even took sides in family arguments, noting on the margins of the transcripts who they thought was right. It's like having had a one-sided relationship with these invisible broadcasters of our tormented souls.

The family made a new life in the US

Needless to say, the documents have been sifted through, parts have been blotted out in black ink, pages are missing. What I have is what was given to me as publishable.

But we now have every letter that my father wrote to us from prison and we wrote to him. Half of the letters are direct transcripts—they were copied out by the censors - while half are paraphrases of what we wrote. There are not always quotation marks to indicate which of the words are ours, which are theirs. It is nearly impossible to detangle the self from the words of the Securitate. Some of the letters were not forwarded to us, so I read them for the first time last summer.

The question of what my father was thinking of when he drove away to Bucharest on 10 March 1983 has lost its painful intensity for us over the years. Yet in the files I see our daily recitation of blame and anger at the time.

That question would have remained unanswered if it hadn't been for a trip to Romania that we took as a family in October 2013. My father was by then 78, my mother 67, so it was a good time to make the journey back.

Walking into my father's prisons, Jilava and Aiud, the cells completely submerged in darkness and bone-chilling dampness, reading the records of his admission to the prison infirmary with fractured ribs and "bruises from hammer applied to fingers", I understood what I could not have understood before.

When he left home, the car stuffed with placards and leaflets, my father knew what he was returning to. Yet he had no choice. For him the family was his country and the country was his family. If he did not fight for everyone else, he could not have hoped to put food on our own table. Or a shred of dignity in our lives. He left us out of desperation and moral conviction.

He protected us by saying nothing to us. But you can only understand this by going into the prison rooms where he suffered. And by standing next to him while he shouts that he has no memory of receiving beatings that fractured his ribs, even though you face him, with the radiography record trembling in your hands. This is the side of heroism no-one likes to talk about, not even him. But it is the face of heroism that now makes me proud.

Slideshow production by Luce van de Weg and Monica Whitlock

Follow @BBCNewsMagazine, external on Twitter and on Facebook, external