10 inventions that owe their success to World War One

- Published

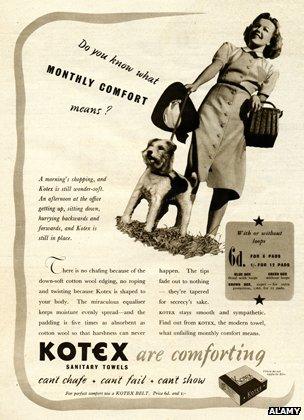

1. Sanitary towels...

A material called Cellucotton had already been invented before war broke out, by what was then a small US firm - Kimberly-Clark. The company's head of research, Ernst Mahler, and its vice-president, James, C Kimberly, had toured pulp and paper plants in Germany, Austria and Scandinavia in 1914 and spotted a material five times more absorbent than cotton and - when mass-produced - half as expensive.

They took it back to the US and trademarked it. Then, once the US entered the war in 1917, they started producing the wadding for surgical dressing at a rate of 380-500ft per minute.

But Red Cross nurses on the battlefield realised its benefits for their own personal, hygienic use, and it was this unofficial use that ultimately made the company's fortune.

"The end of the war in 1918 brought about a temporary suspension of K-C's wadding business because its principal customers - the army and the Red Cross - no longer had a need for the product," the company says today.

So it re-purchased the surplus from the military and created a new market.

"After two years of intensive study, experimentation and market testing, the K-C team created a sanitary napkin made from Cellucotton and fine gauze, and in 1920, in a little wooden shed in Neenah, Wisconsin, female employees began turning out the product by hand," the company says.

The new product, called Kotex, external (short for "cotton texture"), was sold to the public in October 1920, less than two years after the Armistice.

2. ... and paper hankies

Marketing sanitary pads was not easy, however, partly because women were loath to buy the product from male shop assistants. The company urged shops to allow customers to buy it simply by leaving money in a box. Sales of Kotex did rise but not fast enough for Kimberly-Clark, which looked for other uses for the material.

In the early 1920s, CA "Bert" Fourness conceived the idea of ironing cellulose material to make a smooth and soft tissue. With much experimentation, facial tissue was born in 1924, with the name "Kleenex".

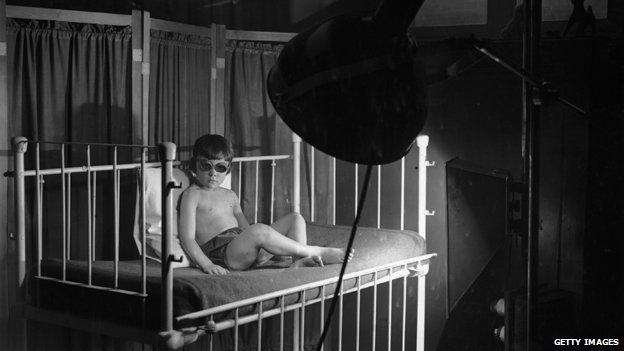

3. Sun lamp

In the winter of 1918, it's estimated that half of all children in Berlin were suffering from rickets- a condition whereby bones become soft and deformed. At the time, the exact cause was not known, although it was associated with poverty.

A doctor in the city - Kurt Huldschinsky - noticed that his patients were very pale. He decided to conduct an experiment on four of them, including one known today only as Arthur, who was three years old. He put the four of them under mercury-quartz lamps which emitted ultraviolet light.

As the treatment continued, Huldschinsky noticed that the bones of his young patients were getting stronger. In May 1919, when the sun of summer arrived, he had them sit on the terrace in the sun. The results of his experiment, when published, were greeted with great enthusiasm. Children around Germany were brought before the lights. In Dresden, the child welfare services had the city's street lights dismantled to be used for treating children.

Researchers later found that Vitamin D is necessary to build up the bones with calcium and this process is triggered by ultraviolet light. The undernourishment brought on by war produced the knowledge to cure the ailment.

Child receiving sun lamp therapy in the 1920s

4. Daylight saving time

The idea of putting the clocks forward in spring and back in autumn was not new when WW1 broke out. Benjamin Franklin had suggested it in a letter to The Journal of Paris in 1784. Candles were wasted in the evenings of summer because the sun set before human beings went to bed, he said, and sunshine was wasted at the beginning of the day because the sun rose while they still slept.

A county border in South Dakota marking one of several time zones in the US

Similar proposals were made in New Zealand in 1895 and in the UK in 1909, but without concrete results.

It was WW1 that secured the change. Faced with acute shortages of coal, the German authorities decreed that on 30 April 1916, the clocks should move forward from 23:00 to midnight, so giving an extra hour of daylight in the evenings. What started in Germany as a means to save coal for heating and light quickly spread to other countries.

Britain began three weeks later on 21 May 1916. Other European countries followed. On 19 March 1918, the US Congress established several time zones and made daylight saving time official from 31 March for the remainder of WW1.

Once the war was over, Daylight Saving Time was abandoned - but the idea had been planted and it eventually returned.

5. Tea bags

The tea bag was not invented to solve some wartime problem. By common consent, it was an American tea merchant who, in 1908, started sending tea in small bags to his customers. They, whether by accident or design, dropped the bags in water and the rest is history. So the industry says.

But a German company, Teekanne, did copy the idea in the war, and developed it, supplying troops with tea in similar cotton bags. They called them "tea bombs".

6. The wristwatch

It is not true that wristwatches were invented specifically for World War One - but it is true that their use by men took off dramatically. After the war, they were the usual way to tell the time.

Cartier Tank watch owes its name to WW1

But until the late 19th and early 20th Centuries, men who needed to know the time and who had the money to afford a watch, kept it in their pocket on a chain. Women, for some reason, were the trailblazers - Elizabeth I had a small clock she could strap to her arm.

But as timing in war became more important - so that artillery barrages, for example, could be synchronised - manufacturers developed watches which kept both hands free in the heat of battle. Wristwatches, in other words. Aviators also needed both hands free, so they too had to throw the old pocket watch overboard.

Mappin and Webb had developed a watch with the hole and handles for a strap for the Boer War and then boasted of how it had been useful at the Battle of Omdurman.

But it was WW1 which really established the market. In particular, the "creeping barrage" meant that timing was everything. This was an interaction between artillery firing just ahead of infantry. Clearly, getting it wrong would be fatal for your own side. Distances were too great for signalling and timings too tight, and, anyway, signalling in plain view meant the enemy would see. Wristwatches were the answer.

The company H Williamson which made watches in Coventry recorded in the report of its 1916 annual general meeting: "It is said that one soldier in every four wears a wristlet watch, and the other three mean to get one as soon as they can."

Even one of today's iconic luxury watches goes back to WW1. Cartier's Tank Watch originated in 1917 when Louis Cartier, the French watchmaker, saw the new Renault tanks and modelled a watch on their shape.

7. Vegetarian sausages

You might imagine that soy sausages were invented by some hippy, probably in the 1960s and probably in California. You would be wrong. Soy sausages were invented by Konrad Adenauer, the first German chancellor after World War Two, and a byword for steady probity - dullness would be an unkind word.

During WW1, Adenauer was mayor of Cologne and as the British blockade of Germany began to bite, starvation set in badly in the city. Adenauer had an ingenious mind - an inventive mind - and researched ways of substituting available materials for scarce items, such as meat.

His began by using a mixture of rice-flour, barley and Romanian corn-flour to make bread, instead of using wheat. It all seemed to work until Romania entered the war and the supply of the corn flour dried up.

From this experimental bread, he turned to the search for a new sausage and came up with soy as the meatless ingredient. It was dubbed the Friedenswurst or "peace sausage". Adenauer applied for a patent with the Imperial Patent Office in Germany but was denied one. Apparently, it was contrary to German regulations about the proper content of a sausage - if it didn't contain meat it couldn't be a sausage.

Oddly, he had better luck with Britain, Germany's enemy at the time. King George V granted the soy sausage a patent on 26 June 1918.

Adenauer later invented, external an electrical gadget for killing insects, a sort of rotary apparatus to clear people out of the way of oncoming trams, and a light to go inside toasters. But none of them went into production. It is the soy sausage that was his longest-lasting contribution.

Konrad Adenauer, towering figure in post-war German politics... and inventor of the vegetarian sausage

Vegetarians everywhere should raise a glass of bio-wine to toast the rather quiet chancellor of Germany for making their plates a bit more palatable.

8. Zips

Ever since the middle of the 19th Century, various people had been working on combinations of hooks, clasps and eyes to find a smooth and convenient way to keep the cold out.

But it was Gideon Sundback, a Swedish-born emigrant to the US who mastered it. He became the head designer at the Universal Fastener Company and devised the "Hookless Fastener", with its slider which locked the two sets of teeth together. The US military incorporated them into uniforms and boots, particularly the Navy. After the war, civilians followed suit.

9. Stainless steel

We should thank Harry Brearley of Sheffield for steel which doesn't rust or corrode. As the city's archives put it: "In 1913, Harry Brearley of Sheffield developed what is widely regarded as the first 'rustless' or stainless steel - a product that revolutionised the metallurgy industry and became a major component of the modern world."

The British military was trying to find a better metal for guns. The problem was that barrels of guns were distorted over repeated firing by the friction and heat of bullets. Brearley, a metallurgist at a Sheffield firm, was asked to find harder alloys.

He examined the addition of chromium to steel, and legend has it that he threw away some of the results of his experiments as failures. They went literally on to the scrap heap - but Brearley noticed later that these discarded samples in the yard had not rusted.

He had discovered the secret of stainless steel. In WW1 it was used in some of the new-fangled aero-engines - but it really came into its own as knives and forks and spoons and the innumerable medical instruments on which hospitals depend.

10. Pilot communications

Before World War One, pilots had no way of talking to each other and to people on the ground.

At the start of the war, armies relied on cables to communicate, but these were often cut by artillery or tanks. Germans also found ways of tapping into British cable communications. Other means of communication such as runners, flags, pigeons, lamps and dispatch riders were used but were found inadequate. Aviators relied on gestures and shouting. Something had to be done. Wireless was the answer.

Radio technology was available but had to be developed, and this happened during WW1 at Brooklands and later at Biggin Hill, according to Keith Thrower a specialist in this area of historical research.

By the end of 1916, the decisive steps forward had been made. "Earlier attempts to fit radio telephones in aircraft had been hampered by the high background noise from the aircraft's engine," writers Thrower in British Radio Valves: The Vintage Years - 1904-1925. "This problem was alleviated by the design of a helmet with built-in microphone and earphones to block much of the noise."

The way was open for civil aviation to take off after the war. Chocks away.

Discover more about the pioneering plastic surgery used to rebuild the faces of injured WW1 soldiers and other innovations, including the world's first blood bank.

Follow @BBCNewsMagazine, external on Twitter and on Facebook, external