The adults who get misty-eyed over Panini World Cup stickers

- Published

The run-up to a World Cup is a time when children start collecting football stickers and cards. But there are also adults who get worryingly misty-eyed, including Ian Shoesmith.

I rip the packets of stickers open with all the excitement and anticipation of the 10-year-old boy that I used to be, and inhale their long-forgotten but oh-so-familiar odour of glue mixed with sticky tape and paper.

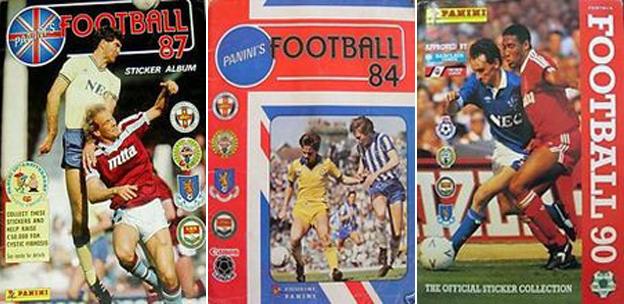

Instantly, I'm back in 1986 and my penultimate year at primary school, when the most important thing in my life was how an England squad featuring Gary Lineker, Peter Shilton and John Barnes would fare at the World Cup.

I am a 38-year-old father with a mortgage and a four-year-old son, Danny.

But my childhood passion - the thrill of racing to the paper shop, handing over all of my pocket money, desperate to be greeted by the mulleted head of a Soviet-bloc defender - is dismissed, out-of-hand, by my son. But I will persist in collecting them - for when he changes his mind. I'm most definitely not collecting them for myself. Definitely not.

Ian Shoesmith and (unconvinced) son

There are lots of grown-ups in the same boat. Adam Carroll-Smith is one of them. The 29-year-old comedy writer from Southsea in Hampshire came across a 1996 sticker album and was desperate to complete his collection.

Rather than merely finding the six missing stickers, however, he tracked down the likes of Lars Bohinen, Stuart Ripley and Philippe Albert in person before recording the whole experience in a book. "It was before my now five-month-old daughter was born - it was a goodbye to that pre-child, feckless time of my life," he says. "Stickers are very evocative of our childhood and have a kind of naivety about them. It's that thing about buying them and seeing a flash of [1990s Derby County striker] Paulo Wanchope when you rip open the packet."

It's easier to hide adult nostalgia when you have a child who is genuinely interested in the stickers. Mark Jensen, editor of the Newcastle United fanzine themag.co.uk, is 48 and has a 10-year-old son. "For about four years he would do them all the time - the cards as well as the stickers," he says. "They were even banned at his school because of all of the arguments they caused. Some kids turned out to be far shrewder investors than others and rip other kids off by swapping the shiny stickers for normal ones and stuff like that."

These bans - relating to either Panini or Topps stickers, or other trading cards - are increasingly common in schools.

Jensen notes that adult family members were often surprisingly keen to buy the stickers themselves, and they remember the ecstasies and agonies of their childhood collecting. "I do remember when I was a kid that there was a conspiracy story that some stickers were impossible to collect - there must be zillions of almost-completed albums out there," he says. "Nowadays I've heard of 'virtual stickers' but they are the antithesis to collecting in my view - you need the physical experience of opening the packet, all of your mates crowding round you to see what you've got."

Carol Mavor, a professor in visual arts at Manchester University, writes about the nostalgia of childhood. "Stickers are very tactile and old-fashioned," she says. "The humanity of touch is also very powerful. That's why people love wooden toys, for example, because they have a unique feel, smell and are real."

Anything up to 15% of children's toys are actually bought by adults for themselves, estimates Richard Gottlieb, publisher of globaltoynews.com and a "play industry consultant".

Adults don't want to let go of their childhood completely, says Mavor. "It seems, without being overly morbid, to be so far away from death, work and the other obligations of adulthood. As adults, we think of ourselves as different people from our childhood selves - the whole world was open to us and it was a free and more creative life."

It's down to sentimental attachment, says Felix Economakis, a chartered psychologist. "Little objects from childhood are imbued with meaning because they remind us of people who may no longer be with us - it's an association with the past through rose-tinted spectacles."

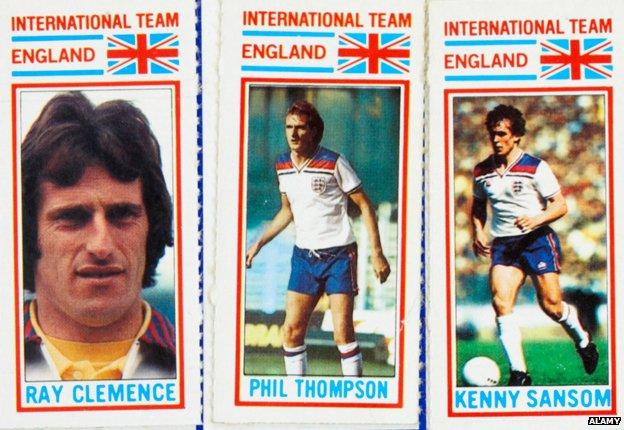

Some stickers are rarer than others

When I think of football stickers, the first person I think of is my late grandad, helping me complete an album while my nana was making chip butties in the kitchen.

There may be a gender difference, Economakis explains. "Men are more into lists, while women tend to collect something with sentimental value. For men, partly it's about status, and collecting for the sake of it."

He also believes that collecting is "quite a solitary activity".

But is it? For me, part of the fun of collecting football stickers was always about swapping duplicate stickers with my mates. Indeed, the chant of "Got! Got! NEED!" while flipping through your handful of stickers has even become a hashtag in the Twitter playground.

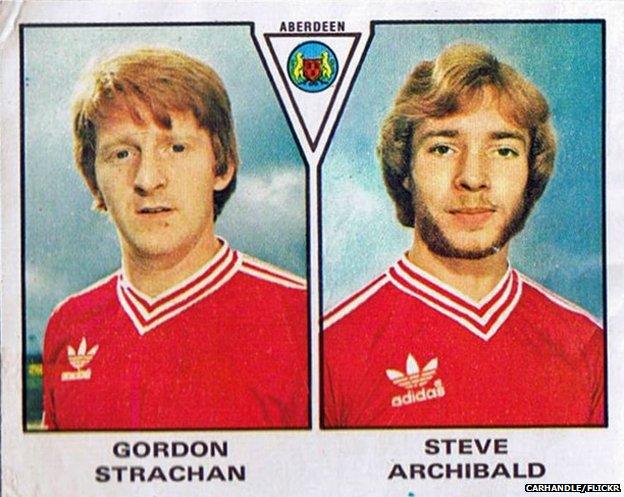

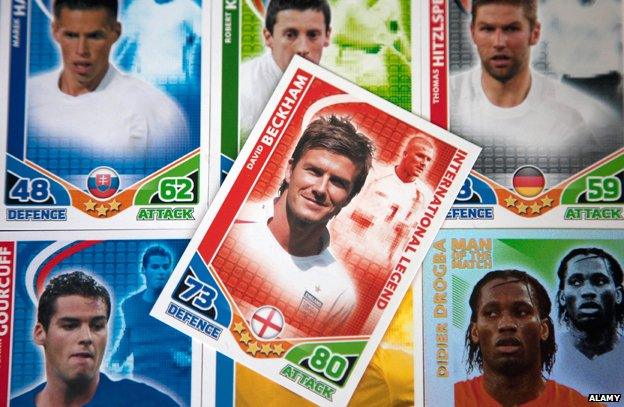

And although the hairstyles and wages of modern-day footballers are barely recognisable from the stars of yesteryear, the fundamentals of collecting remain.

There's the dreaded multiple duplicate - the player whose face seemingly greets you every time you open a fresh packet of stickers.

For me it was former Scotland defender Maurice Malpas. I'm sure he's a lovely bloke - he's certainly a living legend among Dundee United fans - but his memory brings me out in a cold sweat.

Carroll-Smith slowly spells out each syllable of a former Manchester United and Wales utility man. "Clayton Blackmore," he shudders. "I absolutely loathed him. He just seemed to follow me around like a stalker. To this day, whenever I go to Wales I half expect to see him standing there."

So when you come across some obscure Costa Rican squad player for the 20th time this summer, remember that you are not alone.

Fellow addicts are there to help - at a price. They're desperate to trade their mug shot of Iran's goalkeeper, after all.