How Mexican mothers identify sons lost on the trek to the US

- Published

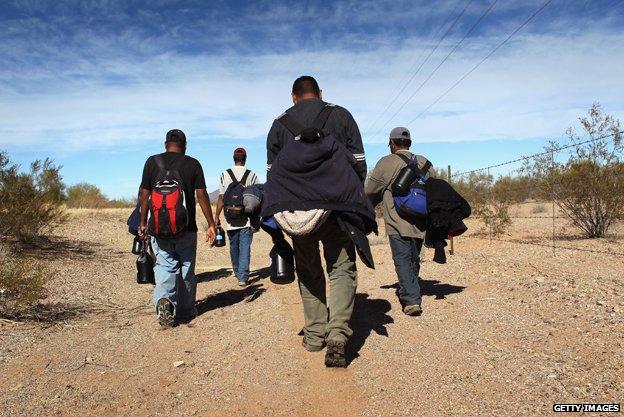

Every year, thousands of Mexicans make the perilous journey across the deserts of northern Mexico and Arizona, hoping for a better life in the US. Not all of them make it, leaving some families with a search for answers - and eventually, bodies.

Carolina Chan's house is a noisy, chaotic place.

Her teenage children, already parents themselves, share the ramshackle two-bedroom home in the industrial town of Ciudad Obregon in northern Mexico. Her grandchildren play boisterously on the patio, running in and out with toys and neighbourhood dogs.

But someone is missing from this scene of domestic mayhem. One morning in 2012, Chan's 19-year-old son, Marco Antonio, left for the US without saying goodbye.

His mother still describes him as a "dreamer".

"He used to say, 'One day, I'll have a nice car, I'm going to live in the US,'" Carolina remembers. "We all took it as kids' games. Even in the final days before he left, I thought he was joking. I never thought he'd try to leave."

Not long after Marco Antonio vanished, Carolina received a message from one of his travelling companions. They'd attempted to cross the Sonoran Desert, which straddles northern Mexico and southern Arizona, in an effort to dodge the US border patrols.

Carolina Chan was eventually spared the uncertainty of knowing her son's fate

Unable to keep up with the pace of the group as they trekked through the harsh border region, he had been left behind in the desert, his friend said.

Immediately, she knew her son's fate.

"When I heard he had been in the desert for six days, I said to myself 'My son is dead,'" Carolina says through the tears. "I came straight home to search Google for anything I could think of. I made call after call after call. I can't tell you how many."

Plenty of mothers who never hear from their sons after they leave home remain forever in a state of uncertainty, not knowing if their children made successful lives in the US, or died en route.

Eventually Carolina's inquiries led her to the Pima County Medical Examiner's Office in Tucson, Arizona. Her initial fears were confirmed.

A dead man had been found in the Sonoran Desert not long after Marco Antonio had gone missing. The face was no longer recognisable, but after a long exchange of emails and photographs, Carolina was able to identify the body as her son's.

Like more than 2,200 other migrants over the past 10 years, Marco Antonio had died on the trek to the United States.

Despite its relatively small size, Tucson has the third highest number of unidentified remains in the US, after New York and Los Angeles.

So overwhelmed were Pima County's forensic investigators that a few years ago they had to start using refrigerated trucks to store all the bodies, which kept arriving at their small office.

"Nobody foresaw this many dead. I didn't," says Dr Bruce Anderson, the forensic anthropologist at Pima County. "When I started here I never could have predicted that this many people would die - and continue to die on a yearly basis."

Anderson's office is awash with thin, colour-coded files. Piles of papers clutter up every available surface and a back wall, known by the staff as the Wall of Shame, is bursting with backdated archives.

Each file represents an unsolved case. "I look at this wall to remind me of the work still to be done, of the many, many people who are presumed to be dead migrants," says Anderson.

"Bodies that are decomposed, mummified, skeletonised, ravaged by animals where only a few bones are left - these people cannot be identified through normal channels."

Together with a postgraduate student volunteer, Robin Reineke, he set up the Missing Migrant Project, external which began the painstaking detective work of tallying the families' often vague missing persons reports with the scores of bodies in the Pima County morgue.

"Many of these families are living in the shadows," says Anderson. "They're either poor and living in Mexico or Central America, or they're living in the United States in an undocumented fashion and they cannot go - or are afraid to go - to the authorities."

He and Reineke now have the biggest database of missing migrants on the US-Mexico border.

Little by little, family members learned about their work and started making direct contact with them in the search for their lost loved ones.

Carolina Chan was one of those desperate family members - another was Emma Grittel.

Emma Gritel in her salon in Puerto Penasco, Mexico

Two weeks after her uncle, Francisco Romero, disappeared in 2010, a man came into her beauty salon in the Mexican resort of Puerto Penasco. He said he'd last seen Francisco in the desert and told her to widen her search beyond the borders of Mexico. She started with US detention centres.

"But he didn't show up in California or Arizona. He wasn't detained. From there we started going to hospitals, town to town. Finally, someone said: 'This is going to sound cruel, but there is nowhere left to look except the desert or the morgue.'"

Often a body will be identified by the smallest of details - a wooden rosary, a family photograph in a pocket, a piece of clothing.

In the case of Emma Grittel, a photo of a withered and sun-blistered tattoo of Jesus Christ on one arm was enough for her to recognise her uncle.

For Carolina Chan, the final clue was even more innocuous - a single button she'd sewn on to a pair of combat trousers her son was wearing.

"The trousers were my husband's," she explains. "But they were too big for Marco Antonio's waist. So he wanted the button moved so that they'd fit." She could never have imagined that the simplest of motherly acts would become so significant.

DNA evidence eventually confirmed the identifications and the bodies were returned home for burial.

Carolina Chan's song for her son

Both women shy away from thinking of the suffering their lost family member endured in the inhospitable Sonoran Desert - exposure to heat of up to 45C (113F) during the day, freezing temperatures at night, hunger, thirst and, eventually, hypothermia.

Rather than express her sorrow in words, Carolina finds it easier to cope with her grief through music. She wrote a song for him called Five Minutes More. "The title of the song says it all," she says, playing the ballad through a tinny speaker on her mobile phone. "I just ask God for five more minutes to be with him, to say goodbye."

Given the chance to talk to migrants planning the same journey as her son, Carolina says she'd only have one thing to say.

"I'd say, 'Look at me - your mother could end up like me.' I'd tell them not to cross. At least not like that - illegally, through such an ugly and dangerous place."

Listen again toThe Missing Migrants on the BBC World Service or download download podcast.

Follow @BBCNewsMagazine, external on Twitter and on Facebook, external