How many middle-aged men need HRT?

- Published

Prescriptions for testosterone drugs have shot up around the world over the last decade. But there is growing concern that they are being over-used and may not be safe.

There comes a point in many a man's life when he starts to feel a bit played-out. Tired. Grumpy. Apathetic. In the US, sports and news channels are replete with ads featuring handsome men with grey hair at their temples, too tired to play basketball and feeling irritable even when they're on a romantic date with a beautiful woman.

The adverts are selling a new disease to the public: Low Testosterone, or Low T. The syndrome even has its own website, isitlowt.com, funded by the pharmaceutical company Abbvie. Men are encouraged to take a Low T "quiz" asking them questions like "Are you sad and / or grumpy? Do you have a lack of energy? Are you falling asleep after dinner?"

That might sound like every middle aged man you know, but if the visitors to the site answer with too many yeses, they are nudged towards having a chat with their doctor. In the US, where direct marketing of prescription drugs is permitted ("Ask your doctor about our new product!") the drugs themselves are promoted too. They vary from pills and injections to gels.

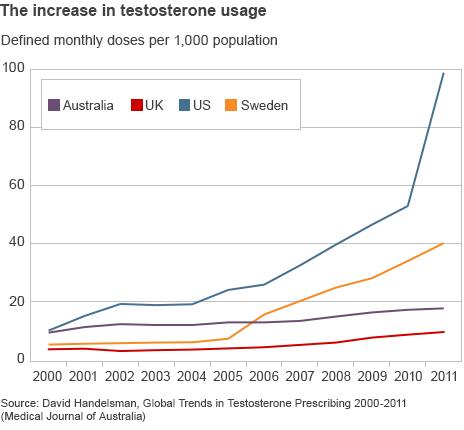

Either an epidemic of lethargy is sweeping men around the world, or the message from the pharmaceutical industry is getting through. Since 2001, prescriptions in the US have more than tripled, to an estimated 3% of men over 40 - 1.7 million men. In the UK, prescriptions roughly doubled over the same period, and the global market for the drugs has increased 12-fold. In 2011, it was valued at $1.8bn (£1bn).

"The question is, is there really any problem here to be treated?" says Dr Lisa Schwartz at Dartmouth College. As the comedian Stephen Colbert jokes, Low T is "a pharmaceutical-company-recognised condition affecting millions of men with low testosterone, previously known as getting older".

Doctors agree that a small proportion of men - about 0.5% - need testosterone therapy. These include men born with genetic diseases or whose testes no longer function after chemotherapy. It was for cases like these that the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) sanctioned the sale of the drugs.

But those aren't the only men with low testosterone levels, and it's thought that the rapid increase in testosterone prescriptions, especially for handy roll-on gels, is going to a wider group of men many of whom have no such conditions.

A man's testosterone levels tend to drop steadily after the age of 40, and can fluctuate from one day to the next.

"At any time in life, your testosterone drops if you're ill for any reason," explains Dr Richard Quinton, a consultant endocrinologist at Royal Victoria Infirmary in Newcastle, England. "And I mean for any reason. If you are up all night, the next day your testosterone will be very low. You have a big meal - that can affect your testosterone level. Any kind of underlying disease can lower your level."

Quinton is one of a number of specialists who believe that a low level of testosterone (referred to by doctors as "hypogonadism") is not a reason to prescribe drugs or gels, in the absence of an observable physical problem or a clinical diagnosis.

Schwartz says there is little scientific evidence that the drugs fix men's lives in the way the adverts demonstrate. "All the testosterone drugs have been approved on the basis that they raise testosterone level - not on the basis that they make anybody's life better," she says.

Part of the appeal of the drugs is they feel like a quick fix to complex - and common - life problems, Schwartz believes. She describes one patient who came to her on a course of testosterone treatment "but he had these waxing and waning symptoms and I was unconvinced that it had anything to do with it". She took the patient off the drugs and he was diagnosed with depression. "He really benefited from therapy," she says.

For its part, Abbvie has defended the way it markets its drugs, and says its awareness campaign for Low T is designed "to educate men about hypogonadism, external to encourage dialogue with their physician".

Many physicians are evidently only too happy to prescribe the drugs. There are also doctors who, while sceptical about the way testosterone is being prescribed, don't share Schwartz's doubts about its ability to make men feel better - and there are positive testimonials from patients, too.

Bill, a retired school teacher in Florida who asked us not to use his last name, had always been a healthy man, known among friends for being constantly active. "People always say to me, 'Don't you ever stop? Your body is constantly in motion.'"

But when he turned 60, he found his energy levels dropped dramatically. "My body was just like I had run a marathon," he recalls. His sexual desire and all romantic feelings "went out the window" - even the desire to kiss or hold hands. He was with a partner at the time, and Bill's sudden change of mood affected their sex life.

He went to his doctor, who prescribed a testosterone gel that he rubbed into his shoulders. Bill's been using the treatment for four years and now, he says, he feels fantastic.

Bill says that testosterone treatment has given him back his life

"Testosterone levels affect quality of life - that is very clear indeed," says Dr Hugh Jones, Professor of Andrology at Sheffield University. "If you talk to the patients that I have on testosterone they are doing more. It's happened several times that people who like dancing couldn't dance and they can dance again."

Jones has worked on a number of studies, with some funding from drug companies, that examine how testosterone may improve mortality. He was one of the authors of a study published last year which showed that men with type 2 diabetes had a higher mortality rate if they had lower testosterone levels, and that the risk of mortality dropped if men were given testosterone treatment.

"Although this was a retrospective study it's one of two studies which has shown that by giving testosterone back it improves survival," he says, although he adds that the treatment is "a mixed bag" that doesn't benefit all men.

"I think that Hugh Jones has done some fantastic, ground-breaking studies," says Quinton. "However, he needs to do bigger ones."

He is worried doctors are about to repeat the "disaster" of hormone replacement therapy (HRT) in women. After observational studies suggested that HRT had a range of positive effects on post-menopausal women - raising sex drive and lowering cholesterol and the risk of heart disease - it was heavily promoted by doctors. Then a randomised control trial was completed which found that HRT increased the risk of breast cancer, heart attacks and strokes.

"It went from being hugely pushed - 'Take this, it's good for you' - to - 'It's poison, it gives you breast cancer, stop!'" he recalls. "It's a rule of thumb for most hormone treatments that they work really well if you're using them to treat someone who's deficient in them. But if you start treating people with other problems then generally they don't - they pop up with adverse effects."

Doctors' attitudes to women's HRT have changed

And some of the adverse effects of testosterone treatment may be popping up now.

A study published in January on PLOS One, external, looked at the medical records of 55,000 men who had been prescribed testosterone. It found that men over the age of 65 doubled their risk of heart attack in the 90 days after being given their prescription - for those over 65 with a history of heart disease the incidence rose from seven per 1,000 per year to 16 per 1000 per year after taking the supplements, for those with no history of heart disease, it rose from four per 1,000 per year to 10 per 1,000 per year..

"A high level of testosterone will drive your red blood cell count up, which is the reason why professional athletes abuse it, because it increases their oxygen carrying capacity," says Quinton. "However, that also makes the blood stickier or more viscous and that may then predispose someone to heart attack or stroke-like events."

Yet the PLOS One study, and others like it, have been criticised since there is no indication that the men in the samples had been monitored to check their testosterone levels weren't overshooting the target, or even that they had been diagnosed properly in the first place. Before being prescribed testosterone, patients should have a baseline measurement taken on an empty stomach in the morning. But research published last year found that a quarter of men in a very large US sample hadn't been tested at all before being prescribed the drugs.

In the face of such poor prescribing, observational studies can only tell us so much. However, when a randomised control trial was attempted in 2010, it was stopped early by the trial's ethics board because the cohort assigned the testosterone drugs were experiencing a noticeably higher rate of cardiovascular-related events. An opinion piece published on Monday in the journal The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology says that large clinical trials of testosterone are "urgently needed".

Notwithstanding the recent studies' shortcomings, in January the FDA issued a safety announcement, external reiterating that testosterone drugs should only be prescribed to men with low testosterone associated with a medical problem, i.e. one that prevents the testes producing testosterone. A number of men have now filed law suits against Abbvie, claiming that the company did not warn them they risked heart attacks by using their drugs.

For Hugh Jones, testosterone therapy is not risky so long as doctors properly diagnose and monitor treatment. "If you pick the right patient and treat them appropriately with that diagnosis, you can change someone's life around," he says.

Although there is no conclusive evidence that the drugs are harmful, Richard Quinton says the results of different trials are starting to "triangulate" and frail, older men should avoid them.

"Testosterone is not the elixir of life. It's a great treatment for men with true testosterone deficiency but it's not a life-extending drug for those who aren't properly deficient."

Correction 31 July 2014: An earlier version of this story referred to two scientific studies on the use of testosterone drugs. The reference to one of these studies has been removed and, in the other case, the results have been expressed more clearly.

Listen to the report on testosterone on The Science Hour on the BBC World Service. Listen to the programme on iPlayer or get the Science Hour podcast.

Follow @BBCNewsMagazine, external on Twitter and on Facebook, external