Why do people take ayahuasca?

- Published

British student Henry Miller, 19, died in Colombia after apparently consuming the traditional hallucinogenic drink ayahuasca, or yage. Emma Thelwell, who took the drug herself, explains why it has become a rite of passage for some backpackers.

I had never swallowed a pill at a party. Yet there I was in the depths of a Colombian bamboo forest, knocking back a liquid containing a psychoactive drug - under the supervision of a shaman who didn't speak a word of English.

During my month in Colombia I didn't join the thousands of backpackers indulging in the country's most famous product - cocaine. But I was sold on ayahuasca. I was intrigued by the fact that for centuries, South America's indigenous societies have used this "teacher plant" in regular rituals.

Ayahuasca, also known as yage, is a blend of two plants - the ayahuasca vine (Banisteriopsis caapi) and a shrub called chacruna (Psychotria viridis), which contains the hallucinogenic drug dimethyltryptamine (DMT). DMT - and therefore ayahuasca - is illegal in the UK, the US and many other countries. Ayahuasca could have serious implications for somebody who has a history of mental health problems, warns the UK's Talk To Frank, external website. The drug could be responsible for triggering such a problem in those who are predisposed but unaware of it.

Ayahuasca is a jungle vine found throughout the upper Amazon region of South America

But in South America ayahuasca is an integral part of some tribal societies. In 2008, Peru's government recognised ayahuasca's status, stating that it was "one of the basic pillars of the identity of the Amazon peoples".

Peru's government claimed that consumption of the "teacher" or "wisdom" plant "constitutes the gateway to the spiritual world and its secrets, which is why traditional Amazon medicine has been structured around the ayahuasca ritual".

"Ayahuasca tourism" is already well established in South America, while its use by Westerners interested in shamanism has raised the profile of the traditional medicine globally, according to the Ethnobotanical Stewardship Council (ESC), external, a charity dedicated to the safe use of traditional plants and whose flagship project concerns ayahuasca.

"The ayahuasca trail in Peru and Colombia is well-travelled, with tens of thousands of foreigners taking ayahuasca there every year," says Joshua Wickerham, chief adviser to the council.

Tourism overall in Colombia has seen a meteoric rise alongside the government's efforts to demobilise left-wing rebels after decades of conflict. The number of international tourists to Colombia increased from 547,000 in 2002 to 2,175,000 in 2012, according to the World Tourism Organisation.

Dr Daniela Peluso, senior lecturer in social anthropology at the University of Kent, says the rise in global tourism has also helped spread the ceremonial practice.

"Whereas, only a few decades ago, the ayahuasca experience required that a lone traveller make his or her way to the forests of South America, now notions of local and global spaces converge as shamans and tourists travel throughout the world to perform and participate in a diversity of ayahuasca ceremonies," she says. Not forgetting of course, that importing the substance to many countries would be a serious criminal offence.

Though scientific evidence of the clinical benefits of ayahuasca is limited, advocates say it has become increasingly popular as a tool to treat post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depression, and addictions.

"Most people seek ayahuasca with good intentions - they are not thrill-seeking but are curious, serious - or have specific issues such as depression," says botanist Prof Dennis McKenna, from the University of Minnesota.

"Thrill seekers are self-eliminating after a couple of sessions of vomiting," adds McKenna, who is a board member at the Heffter Research Institute, which investigates psychedelic substances. "It is not pleasant or fun. It puts your body through the wringer - emotionally and physically."

Certainly when I ventured out to the midnight ceremony at a shaman's farm with four other "gringos", I wasn't looking for a party. In fact, from what I had heard not much really happened to you - I was just curious about a local ritual.

What I found was a Colombian community group who met each week to drink the teacher plant with their local shaman as part of a learning and healing process.

Though we were a group, it was a singular experience. After drinking the vile, bitter mixture, we found our own space around the farm - we lay on mattresses or watched the fire to the sound of Andean musicians.

Some people vomited at times, some cried, some slept. Mostly people were quiet, with the only sounds coming from the musicians and the occasional chant from the shaman.

I spent a number of hours in a conscious but dream-like state. I wasn't sick but I did feel physically uncomfortable and disorientated for a time.

I was expecting to see at most perhaps an explosion of colours, but I was surprised to experience powerful, meaningful visions of childhood memories. After a few hours the effects wore off and I was left with a peaceful, happy feeling.

It is a ritualistic learning process that is becoming increasingly popular across the globe, with people exploring their personal development through the introspective nature of the hallucinogenic experience, according to the International Center for Ethnobotanical Education, Research & Service (ICEERS), external.

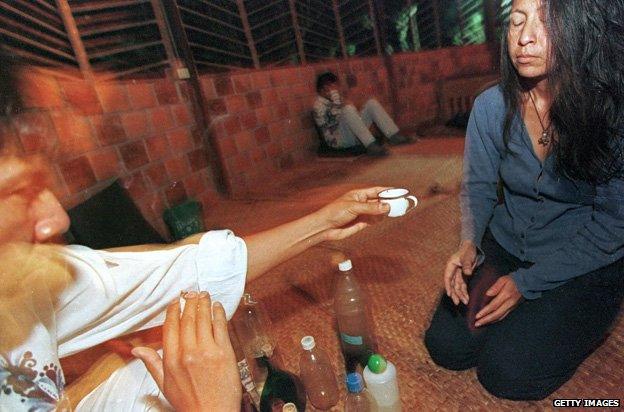

Ayahuasca being prepared Photo: flick/jairinflas

Career coach Jeremy Behrmann took ayahuasca in Colombia over several weeks in 2013 as part of the research for his book, Breakaway, which helps people design gap years and sabbaticals.

"I took ayahuasca with a fourth-generation shaman to explore its ability to provide 'visions' that could give my readers further clarity on their vocational calling," says Behrmann.

"Many travellers I met took it because they'd been told it had effects similar to other drugs like LSD which are often used recreationally. In my experience people should only seek the medicine and the well-trained shamans who hold the ceremonies with the intention of engaging in a serious spiritual upheaval. My experience was hugely enlightening, but ultimately very challenging."

Indeed, not all shamans are well trained, McKenna warns.

The city of Iquitos in the Peruvian rainforest, for example, may be the epicentre of retreat centres but it's also the "wild west" of ayahuasca, he says. Here, tourists can buy cups of ayahuasca on the street - with no way of knowing who concocted it.

Though overdoses are rare, some less scrupulous locals are mixing up "lousy brews" which contain "toe", a member of the nightshade plant family. This can leave people in a more vulnerable and confused state and is done often for nefarious reasons - to rob or sexually abuse people, warns McKenna.

"After starting the ceremony, participants are largely immobilised for four to six hours, so it is important to have trust and be in a safe place," says Wickerham.

Ayahuasca is only legal in Peru as part of a spiritual ceremony, it is not supposed to be taken unsupervised. Though there is little government oversight, the Colombians are organising a guild of shamans to ensure good practice.

A responsible shaman should check to see what medication people are on before they take ayahuasca, says Wickerham, and they will know about potential bad reactions it may have with other medicines - most specifically antidepressants.

Ultimately my experience was positive, but there is a risk - and people must take care choosing who they drink ayahuasca with.

Follow @BBCNewsMagazine, external on Twitter and on Facebook, external