Why is Glasgow the UK’s sickest city?

- Published

Babies born in Glasgow are expected to live the shortest lives of any in Britain. One in four Glaswegian men won't reach their 65th birthday. What is behind the "Glasgow Effect" and can it be prevented?

The pool is full on Sunday afternoon in the Glasgow suburb of Easterhouse. Children are splashing around and shooting down water slides while a man with heavily tattooed arms swims a rhythmic front crawl up and down one of the lanes.

It is a picture of vigour and health in the city, which is hosting the 2014 Commonwealth Games this summer.

Glasgow is internationally renowned for its thriving arts scene and top universities. It boasts handsome Victorian architecture, smart designer shops, fashionable bars and restaurants.

At the same time, this dynamic city also has an unenviable reputation for poor health. Obesity rates are among the highest in the world. Research conducted in 2007, external found that nearly one in five potential workers was on incapacity benefit and that Glasgow has a much larger number and a higher proportion of the population claiming sickness-related benefit than any other city in Britain.

New flats in Gorbals in the 1960s

Gorbals in the 19th Century

Tenements that had been built quickly and cheaply defined the area

Crowded housing was replaced with high-rise towers in the 1960s

Queen Elizabeth Square was an early experiment in high-rise housing. The area was demolished in 1993

2014: Areas of Gorbals have been redeveloped

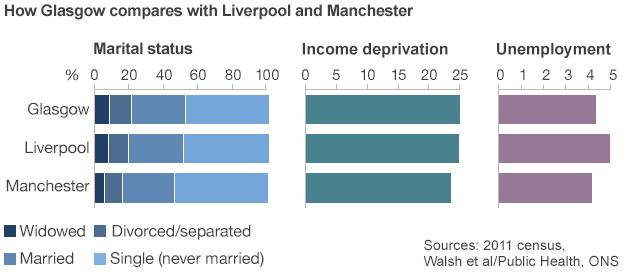

What is worse, the city has an alarmingly high mortality rate. A 2011 study, external compared it with Liverpool and Manchester, which have roughly equal levels of unemployment, deprivation and inequality. It found that residents of Glasgow are about 30% more likely to die young, and 60% of those excess deaths are triggered by just four things - drugs, alcohol, suicide and violence.

Moreover the Glasgow Effect is relatively new. "These causes of death have emerged really since the 1990s," says Harry Burns, professor of public health at Strathclyde University. "And they emerged more dramatically in one particular sector of the population - men and women between the ages of 15 and 45. So it's a very specific pattern affecting people in their most productive years."

Walter Brown, a man with a lined face and cropped grey hair, says he has had a lucky escape. As he sits nursing a cup of coffee in the cafe next to the swimming pool, he describes his agonising battle with alcohol. "The thought of giving up terrified me," he says. "Because what else do you do? Everybody I knew drank or took drugs."

He adds: "It allowed me to wear a mask - I was Jack the Lad, the tough guy full of bravado. Before I went out I would drink a quarter of a bottle of whisky and two cans of lager just to become the person people thought I was by the time I walked into the pub."

Walter suffered alcoholic seizures, temporary paralysis and cirrhosis of the liver. His doctor warned that even another litre of drink could cause permanent brain damage and even death. But that didn't put him off. "Somehow I didn't think it would happen to me," he says. "And I thought we're all going to die young anyway - we all eat rubbish and [the] government isn't going to give the likes of me a job."

Eventually, at his daughters' insistence, Walter did stop drinking and now has a job running a club for recovering addicts which meets at The Bridge centre on Sundays. Some go for a swim, others take part in music workshops or simply hang out in the café.

Over the past decade, Walter says he has heard of eight cases of suicide in the housing scheme where he used to live in Glasgow's impoverished East End. "One was a friend - I never suspected that he was somebody who could do that. He just went home and hung himself. And there were others - guys you've seen in the pub. You'd ask them - how you doing? Then all of a sudden, they're gone - their lives ended."

Homicide rates in Glasgow have come down by nearly 40% since 2007 - partly believed to be the result of an innovative police project tackling knife crime. Yet per head of population, the city still has twice as many murders as London. Drug abuse is also rife.

What explains so much self-destructive behaviour? Psychologists, epidemiologists, sociologists and others have long puzzled over what it is about Glasgow that fatally undermines health and wellbeing.

Moira's story

Moira lives in Glasgow's East End, in an area ravaged by drugs and her own family has paid a heavy price. She had two daughters. The elder one lost custody of her children thanks to her addiction. The younger one lost her life. Moira, who is overweight, and suffers from emphysema and mobility problems, has brought up her two grandchildren virtually single-handed. Her husband couldn't help her - he died of a sudden heart attack just after his 50th birthday. Her eldest daughter got pregnant at 18 and had a violent drug-addicted, partner who was eventually jailed for attempting to murder her.

"She could no longer look after the kids because, as you can understand, she was in a terrible state," says Moira. Then Kirsty, Moira's second daughter, died of an overdose. "When we got the toxicology report, she'd taken something from her husband's drawer. I don't know what she thought she'd taken but it killed her. She was my rock you know and I dearly miss her." Stephanie, Moira's 20-year-old granddaughter, admits she is worried by her family history. "It kind of makes you think what if that turns out to be me in the future? So I try and stay away from it all," she says. "But it's hard. Because living in the east end of Glasgow, it's alcohol and drugs everywhere you go."

Harry Burns, who until recently was the country's chief medical officer, has his own theory. He raised a few eyebrows when he compared Glaswegians to Australia's Aboriginal people. Yet he believes deindustrialisation in a city where tens of thousands once worked in the factories and the shipyards has deeply wounded local pride. As a result, people here have much in common with demoralised indigenous communities.

"Being a welder in a shipyard was a cold and difficult and dangerous job," he says. "But it gave you cultural identity in the same way as native peoples in Australia once had a very intense history and tradition."

He scoffs at the cliches about people suffering coronary attacks after eating those infamous deep fried Mars Bars. "No one is saying that Glaswegians are models of healthy behaviour but the evidence that we are where we are because we eat vast amounts of fat or smoke vast amounts of cigarettes just isn't there. That's not the explanation."

Instead he is convinced that the social and economic problems that Glasgow has experienced over the past few decades have come together in what he calls "a perfect storm of adversity". Burns points to a succession of graphs which show Scots do not smoke more than other Europeans nor do they suffer more heart disease. In fact, under his stewardship, Scotland was the first part of Britain to ban smoking in public places.

No Mean City

The Gorbals, an area south of the river Clyde, was once a byword for downtrodden, overcrowded slums. The 1935 novel No Mean City helped give the area its notoriety

The story of urban decay breeding violence features Johnnie Stark, who becomes the unchallenged Razor King of a Gorbals gang

The novel enraged many in the city, with The Glasgow Evening Times arguing that it had branded the city "a collection of thugs and harlots" and was the "worst possible advertisement Glasgow can have when the city is striving to live down its evil and undeserved reputation"

The vision of the Gorbals depicted by author Alexander McArthur has long since disappeared

"Where traditional communities lose their traditional cultural anchors," he says, "They all find the same things happening - increasing mortality from alcohol, drugs, violence. The answer is not conventional health promotion. Where you lose a sense of control over your life there's very little incentive to stop smoking or to stop drinking or whatever. The answer is to rediscover a sense of purpose and self-esteem."

Some do rediscover that sense of purpose - in a Govan workshop hammering and chiselling wood. The Galgael Trust provides men and women with a 12-week joinery course to help counter addictions and other health problems. This community carpentry, its proponents say, is really about fostering friendship and rebuilding confidence.

Tam McGarvy, the heritage and culture worker at Galgael shows off boats made by trainees and intricate wooden sculptures of animals. The charity aims to create a sense of wellbeing in people who have been broken by society. "This used to be one of the biggest shipbuilding centres in the world for 150 years then we had the big legacy with several generations ending up unemployed," he says.

"What we try to do is a kind of alchemy. People have been put on the scrapheap as wasted, rotten metal and we like to turn that base metal into gold again."

Jock, a man in his late 20s, is carving Celtic dragons on to a strip of wood. He was referred to Galgael by his doctor after suffering palpitations, panic attacks and acute agoraphobia. "About a year and a half ago I just completely switched off - I locked my door and didn't leave," he says. "Coming here I got used to being around people again - it just gave me an outlet to be social."

The Glasgow Effect might well be alleviated by social integration projects. But its roots are, according to some, so deep that you also have to go further back for an explanation.

A few miles from Galgael, in the affluent West End, there is a woman with her own theory - one which is also tied up with the history of this city. Author Carol Craig says to understand Glasgow's early deaths you should look not to the end of the shipyards and factories but instead to their beginning.

Galgael Journey On participants at the work benches

In the early 18th Century, Glasgow was described by the author Daniel Defoe as "the cleanest and beautifullest and best built city in Britain". But when the Industrial Revolution drew thousands of people from Ireland, the Lowlands and Highlands, the population exploded and for many it became a living hell.

"I was so struck by the very nasty and aggressive relationship between men and women historically in Glasgow," Craig says. "And that was partly as a result of the terrible overcrowding - it was worse than England. Having a front room or parlour was practically unheard of."

She explains that in 1891 the London County Council defined overcrowding in terms of two or more person in a room. In the metropolis one third fell below this standard but in Glasgow two thirds - or twice London's number - of residents lived in overcrowded accommodation.

Enforced proximity, she argues, forced men out of their homes and into the pub. "It was a kind of survival mechanism," she says. "In the old Glasgow on a Friday when men got paid, you would see women queuing outside workplaces and pubs to retrieve any of the money. This was very much a city where men suited themselves."

In her 2010 book, The Tears That Made the Clyde, Craig suggests that rapid industrialisation in Glasgow produced a toxic masculinity which destroyed family life.

According to the Glasgow and Clyde Health Board, in just two years almost half of all homes in the city will be single-adult households.

"There is a failure of personal relationships in Glasgow that no one is facing up to," says Craig. "This is significant because what is the single most important thing for men's health? It's being married - it can account for as much as seven years of life expectancy. So if we want to find out why health in Glasgow is so poor I think one of the things that we should ask about is relationships."

Burns agrees that relationships are key. He talks about the need to build "social capital" so individuals can offer each other friendship and mutual support. He is also heavily influenced by the Israeli-American sociologist Aaron Antonovsky, who coined the term "salutogenesis" to describe an approach which focuses on a positive view of wellbeing rather than a negative view of disease.

During his lectures, Burns has a favourite slide which shows the molecular biology of a hug. "When you hug a baby you make them happy," he says. "Happiness is associated with the production of neurotransmitters in the brain. One of these neurotransmitters has an effect on a particular gene which activates the production of a protein that allows the brain to suppress the stress response. Failure to nurture a baby - failure to do something as simple as hug a child - interferes with that process."

Burns believes in early intervention and there are many organisations now devoted to this. Lickety Spit, a pioneering theatre company, creates plays for three and four-year-olds in the most deprived parts of Scotland. It fires children's imaginations but even more crucially perhaps it encourages parents to get down on their hands and knees and bond with their offspring.

Lickety Spit aims to spark the imaginations of young children

It has taken decades to create Glasgow's current problems. It will take decades to fix them. And some do not like the term Glasgow Effect.

One of the academics who wrote the original research - Investigating a Glasgow Effect - now hates the term and describes it as "deeply unhelpful". David Walsh of the Glasgow Centre for Population Health believes some have misunderstood or trivialised the dilemma facing the city. "Some journalists are excited by it as if it were some kind of Scooby Doo mystery but let's not forget that we are talking about people who have died."

The excess mortality phenomenon is a "horribly complicated" set of factors affecting different parts of the population in different ways so it's pointless searching for a "silver bullet" to solve it, he believes. Walsh says that he originally identified 17 different factors.

Some blame the cold, rainy weather and say a lack of sunlight has caused chronic vitamin D deficiency. There are theories ranging from Glaswegians' penchant for burning the candle at both ends to a culture of pessimism. Some think sectarianism between Catholics and Protestants could be responsible. Scotland's health minister Alex Neil accused Margaret Thatcher of driving the Scots to drink and drugs by destroying heavy industry back in the 1980s. Local Conservatives described the claim as preposterous and said alcoholism was too important to be treated as a political football.

What's certain is that there are no easy answers. Even in the better off neighbourhoods, mortality rates are 15% higher than in similar districts of other big cities. Burns is perplexed by this but suggests hidden influences upon the genes could be responsible.

"A lot of those middle-class people will have been very poor somewhere in their family tree," he says. "And this takes us into the field of epigenetics - the business of genes being switched on or off depending on the environment you were brought up in. There is an epigenetic impact of the diet that your parents or grandparents were exposed to. Now we can easily find scientific explanations for this - we just haven't proved it yet."

The idea that the lifestyle of your grandparents - the air they breathed, the food they ate - can directly affect you, decades later, is disorientating. Many would argue it smacks of fatalism. What is the point of trying to be healthy if you are doomed by your ancestors' bad habits?

The epigenetic notion goes against conventional views that DNA carries all our heritable information and that nothing an individual does in their lifetime will be biologically passed to their children. But when it comes to the Glasgow Effect perhaps no theory can yet be discounted.

Lucy Ash's report, The Mystery of Glasgow's Health Problems, can be heard on Assignment, on BBC World Service on Thursday 5 June. See the schedule for broadcast times or catch up on BBC iPlayer

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.