Making maple syrup - the traditional way

- Published

Now that Canada's harsh winter has given way to spring, the annual ritual of gorging on maple syrup has begun. While most farms have adopted modern technology, there are still a few people making maple syrup the old-fashioned way.

It's a vision of perfect Canadiana. Walking in thick fog through a maple forest, there's still snow on the ground but the thaw has set in and sugary sap is rising up through the trees, dripping into tin buckets attached to the trunks.

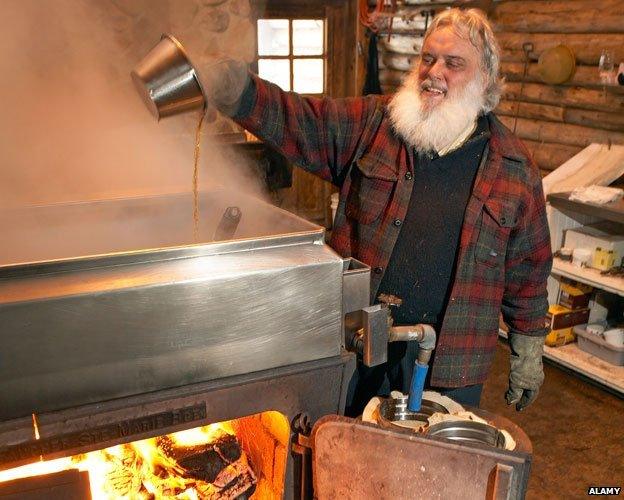

I make my way to a log cabin. Inside, standing by a roaring fire, is Pierre Faucher who greets me with a silent "ho, ho, ho," rolling his head back and forth, his eyes filled with amused interest.

Faucher is the owner of what Canadians call a "sugar shack" where maple syrup is made.

In the spring, Canadians traditionally get themselves down to the nearest one to gorge on high calorie, artery-clogging fare.

Meatballs, sausages, beans, pies, bacon are all slathered in maple syrup - like a reward for getting through the harsh winter.

Glass of maple wine in hand, I'm enjoying the sepia-tinged folksy moment. Isn't this what it's all about? The folklore, the dizzying whirl of fiddle music in the background and the drip, drip, drip of maple sap into tin buckets?

Not exactly. In this most symbolic of Canadian industries, times are changing fast - today, maple syrup is a multi-billion dollar industry.

Forget the buckets - most farms these days have their trees hooked up to miles of tubing and vacuum pump the sap into tanks.

With today's wireless monitoring systems they can check progress without getting their feet soggy in the bush.

Not Faucher though - he's one of just a few farmers who still produce their syrup the old-fashioned way.

At the first signs of spring, he and his four men trudge through 120 acres of maple forest, waiting for that perfect moment - when night-time freeze and daytime thaw conspire to get the sap moving through the trees. This is when they tap the trunks and hang their buckets.

It's a laborious and time-consuming craft but he isn't tempted to modernise.

"The guy who wakes up in the morning and works from the kitchen table - he doesn't see the ice sparkle, doesn't see the first flower, doesn't smell the ground defrosting," he says. "It's about how much the trees are going to produce, how much money he's going to make."

In 2012, Canadians got a sense of the value of maple syrup when 18 million Canadian dollars ($16.5m; £10m) worth of the stuff - enough to fill 150 tractor trailers - was stolen from warehouses in Quebec.

The Quebec industry, which accounts for about three quarters of the global market, is united in a powerful legal cartel - this is a hard-nosed, competitive industry.

When I speak to the owner of a hi-tech farm north of Montreal, Christian Rail, I find that he only needs to glance at his smartphone to tell how much sap has been pumped.

He can even tell if squirrels - the bane of the maple farmer's life - have been gnawing at the tubing. For him, any farm serious about production has to keep up with the times. "We wouldn't be able to provide the world with maple syrup with buckets," he says.

Quebec's modern farms supply up to 80 per cent of the world's maple syrup

It's a stark contrast to Faucher's sugar shack, where sap is boiled down to syrup on a gigantic wood-burning stove. A young man in a baseball cap, Pierre Rozon, is on duty, ladling the bubbling liquid with a pan to check its consistency.

Only when it has reached a temperature of 104C (219F), its gloopy flow breaking as it falls from the pan, does it become syrup. Occasionally, he drags a length of fatty bacon rind through the mix. "The fat stops it bubbling over," he says.

He's been doing this since he was a little boy, in this very sugar shack.

Faucher has a go at stirring another pan of syrup for taffy - a thicker concoction that is poured directly onto the snow and twirled around a stick to make a sort of lollipop.

"If I had the chance, I'd spend all my time in the shack boiling the sap," he says wistfully.

His farm exists in its own little time warp and there's something of the rugged individualist about him, like the pioneers who first settled the land in the 17th century.

He is one of the last maple farmers in the country to preserve this craft. Somehow, it seems the syrup tastes all the sweeter for it.

How to listen to From Our Own Correspondent, external:

BBC Radio 4: Saturdays at 11:30 and some Thursdays at 11:00

Listen online or download the podcast.

BBC World Service: Short editions Monday-Friday - see World Service programme schedule.

Follow @BBCNewsMagazine, external on Twitter and on Facebook, external