'All Honour to You' - the forgotten letters sent from occupied France

- Published

The remarkable discovery of a box of letters in the archives of the BBC is shedding new light on conditions and attitudes in France during World War Two.

The letters - about 1,000 have survived - were sent to London from just after the French surrender to Germany in June 1940, through to the end of 1943.

They were addressed to the French service of the BBC, otherwise known as Radio Londres, which during the German occupation was a vital source of information and comfort for millions of French men and women.

Extracts from the letters were read out on Friday evenings on a programme called The French Speak to the French, whose aim was to build morale and stiffen civilian resistance to the Germans and Vichy.

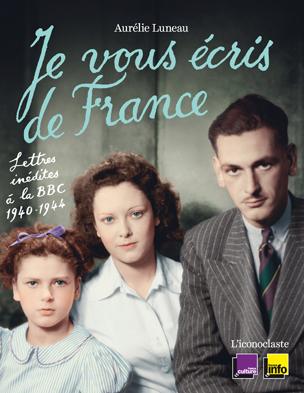

After the war, the letters were put in storage and forgotten. That was until historian Aurelie Luneau stumbled upon them while researching her thesis on Radio Londres.

"I was in this tiny room in the BBC archives in Reading, and they brought me a box marked 'Letters from France'," she says. "One look inside and I knew it was one of those finds that historians normally only dream about."

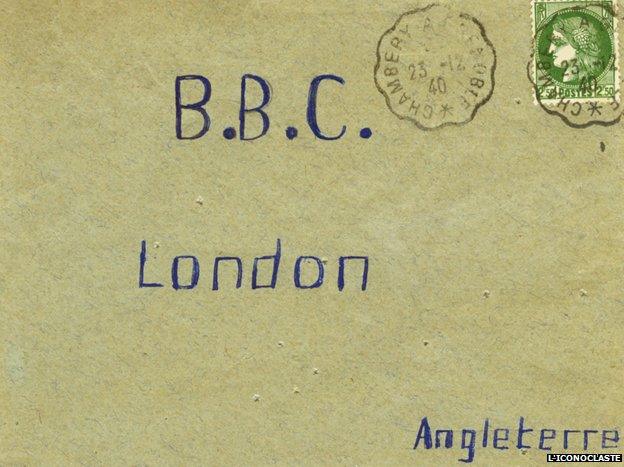

Remarkably, for a good part of the war it was still possible to post mail from France and for it to reach London.

If you lived in the unoccupied Vichy zone - it was not until the end of 1942 that the whole of France was occupied by the Germans - you simply affixed the correct stamp and took it to the post office.

Many of the letters and cards have the most basic of addresses, such as "BBC, London".

The post had to pass through the Vichy censors' office which checked some 360,000 letters every week but evidently there were sympathetic members of staff because during 1941 and 1942 around 100 letters a month got through.

Some letters even had messages appended in the censor's own hand, saying things like "I agree".

Letters from the German zone could easily be smuggled through to the unoccupied zone and then sent on. Others came via friends in Switzerland or Portugal, or the US consulate in Lyon.

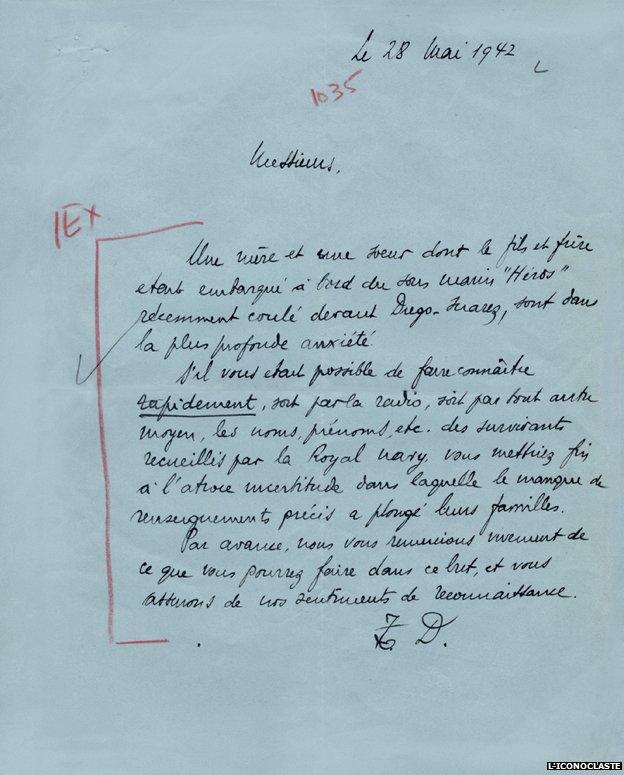

Once in Britain, the letters were first read by military intelligence before being passed on to Radio Londres. Many still bear the annotations of British intelligence officials.

Most of the letters were sent anonymously or signed with pseudonyms or initials - only occasionally is there a full name. The risk was great, if the writers were identified.

"The letters come from people in every walk of life - workers, intellectuals, farmers. And they deal with every kind of subject - the hardships, the shortages, the arrests, denunciations of collaborators, small acts of resistance," says Luneau. "Some even give maps showing the RAF where to bomb."

In March 1941 a correspondent signing himself N.S. writes from Nantes to describe what happened in the local cinema when a newsreel came on showing a meeting between Hitler and Mussolini.

"Oh you should have heard the din! Everyone was whistling and shouting and stamping their feet, cursing these two old cronies with words that I dare not repeat.

"In the next seance, the audience was told that during the newsreel there must be silence… so when the moment came, the whole of the auditorium succumbed to a sudden and noisy cold! Everyone was coughing and sneezing!"

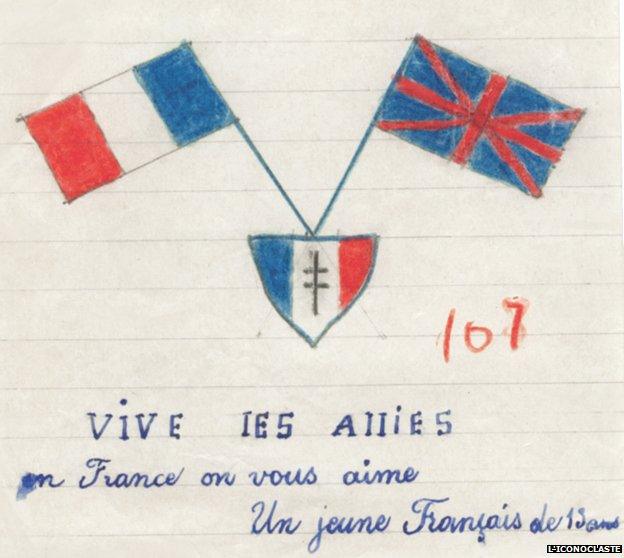

And here is another small act of defiance, sent from Alsace.

"In Saverne a huge Swastika was hoisted above the castle ruins. But it was torn down and replaced by a French tricolour.

"The heroes who did this carried it out to perfection, because they also entwined the flagpole with barbed wire and removed the crampons that were used for climbing up the tower.

"The next day the population enjoyed the ridiculous scene of the Wehrmacht attempting to shoot the flag down with a machine gun!"

The control room at BBC Bush House, 1943

Other letters convey the changing mood in France. At first correspondents are reluctant to criticise Marshal Petain, the World War One hero who ruled from Vichy. But gradually their patience with him is eroded.

In July 1941, a woman signing herself The Stenographer writes: "While continuing to respect the Marechal - because it is impossible to believe him capable of treachery - the French people no longer believe in him. He has become a mere figurehead, a facade."

And in December 1942, a letter signed 22 Mother Hens reads: "You should see the cinemas when the news come on and they show the Marechal. Total silence. Not one person claps."

Many of the letters are published in a new book

From mid-1942 the persecution of Jews in the occupied zone is stepped up, with the compulsory wearing of the yellow star. A regular correspondent calling himself William Tell, who gets his letters out via Switzerland, describes the scene in Paris.

"In Belleville and Menilmontant (working class areas) there are many Jews, small artisans for the most part. They get together in little groups and anxiously discuss the news from the night before. It is very distressing to see the women and the children of six or seven years of age."

Later there are signs of impatience with the Allies, as the French wait helplessly for the long-announced second front. But by 1943, and especially after the German surrender at Stalingrad in February of that year, morale is rising.

Around this time N.S. (again) recounts a scene from the Paris metro.

"There were two German soldiers in our wagon as well as a navy officer. Then an old French wounded veteran from the First War got on, wearing all his medals, and when he saw the Germans, he launched into this diatribe - You Germans, kaput! Your women, your children kaput! Soon you'll see how things are and there won't be one of you left!

"The three Boches didn't say a thing. But the navy officer, who was standing there impassive and slowly nodding his head, had tears running down his cheeks."

Charles de Gaulle broadcasting from the BBC studios in London, 1941

The stories told in the letters were of vital importance to De Gaulle's Free French in London.

They allowed the movement - and indeed British intelligence - to gauge opinion in France and also to judge the impact of their propaganda effort conducted via the BBC.

It is estimated that some 70 per cent of French households with a radio set turned in to the BBC during the war - and even today the reputation of the BBC in France owes much to the collective memory of those days.

Throughout all the letters, the one constant theme is gratitude for keeping alive the cause of freedom.

In December 1944, a teacher called Monsieur Godard - it was after the Liberation so he could use his real name - sent a poem of thanksgiving to the BBC, written by his daughter.

The last couplet reads: "Le Monde entier tournant les yeux vers vous / Crie, Merci, BBC, Honneur a vous!"

The Whole World turns its eyes on you / And shouts, Thank You BBC, All Honour to You!

Follow @BBCNewsMagazine, external on Twitter and on Facebook, external