The invisible killer threatening millions of migrating birds

- Published

Every year, hundreds of millions of birds are killed or injured when they fly into windows. Volunteers who document the collisions are now calling for architects and landlords to make their buildings more bird friendly to reduce the number of deaths.

Sometimes birds see plants or empty spaces beyond the windows - sometimes they just see the reflection of the sky or trees, but not the glass itself.

Most tend to cruise at 20-30mph (32-48kph) - if they hit a window at that speed the impact is usually fatal as their beak is jammed back into the brain.

Although collisions can happen anywhere, they are most common in cities where big glass buildings proliferate.

Local birds seem to learn where they can fly safely but migratory songbirds such as warblers, thrushes and sparrows have a particular problem identifying glass.

They usually fly by night when they are less visible to predators and use the stars to navigate - but they appear to get confused by the illumination of towns and cities below.

Drawn down by the lights, the birds stop to rest and refuel. Some hit windows as they descend but it is more common for them to run into trouble the next day on the way back up, when reflections are stronger - research suggests that the majority of collisions happen on the lowest six storeys of buildings.

The birds are often distracted looking out for predators and food so "what's in front isn't necessarily more important than what's behind them or to the side," says Christine Sheppard, bird collisions campaign manager at the American Bird Conservancy.

Reports of mass collisions date back to the late 1800s when powerful electric lights were introduced, she says. Dead birds were often found at prominent illuminated structures such as the Empire State Building and the Washington Monument.

Today, groups of volunteers patrol nearly 20 North American cities during the spring and autumn migration seasons to document the number of casualties and lobby for the owners of buildings to turn their lights out at night.

The idea began in Toronto in 1993 - since then, the city's Fatal Light Awareness Programme, external (Flap) has recorded more than 66,000 collisions involving 166 species.

.jpg)

Birds collected by volunteers in Washington DC during 2013

Though overlapping migratory pathways stretch across North America, some cities are thought to present particular problems.

"Toronto is one of those urban centres that was built in the worst possible location for this kind of issue," says Michael Mesure, Flap's founder. "It sits on one of the busiest migratory corridors on the planet."

One day, 12 years ago, they stopped counting after picking up 500 bodies in a single place.

Further south in Washington, volunteers cover an four-mile (6km) route every day during the migration season, setting off before dawn and skirting round the edges of buildings thought to be especially problematic to record the number of collisions.

Often they find a handful of birds - occasionally they find none, but they only cover a tiny fraction of the city.

They have to work fast - gulls and rats may find the dead birds first, or street cleaners may sweep them up. Hotel owners sometimes clear away birds in the morning so as not to upset guests, while crows have been seen waiting in trees, then swooping in to catch a bird before it hits the ground.

The documentation of bird collisions is slowly becoming more thorough and Flap has developed a web mapping tool, external that allows people around the world to report cases.

Difficulties involved in conducting accurate surveys over large areas mean there are big margins of error when it comes to the statistics. The best current estimate for the US, made by Scott Loss of Oklahoma State University, is between 365 million and 988 million bird deaths each year.

While there is no proven link between collisions and the decline in some bird populations, "there's a good chance that some species are being affected in some locations," he says.

He suggests some land-bird populations are being eroded by 2-9% each year - a rate that could have a lasting impact on some species.

The collisions are particularly worrying because they are indiscriminate, says Daniel Klem, professor of ornithology and conservation biology at Muhlenberg College.

He pioneered the study of window strikes four decades ago and found the fittest members of the population were just as likely to die in this way as weaker birds.

"You may be killing some very important members of the population that would be instrumental in maintaining its health," he says.

Klem has watched glass proliferate as a building material, even in bird conservation areas.

"We have some of our most prestigious ornithologists working on conservation issues who work in buildings that are palatially covered with glass," he says, frustrated that some architects and developers seem unaware of the issue.

"My suspicion is that this is very unfriendly or uncomplimentary to them - dead and dying, and it's associated with their products."

For those who want to prevent collisions on their buildings, the options, so far, have been limited.

The new US embassy in London will have an "envelope" designed to prevent bird collisions

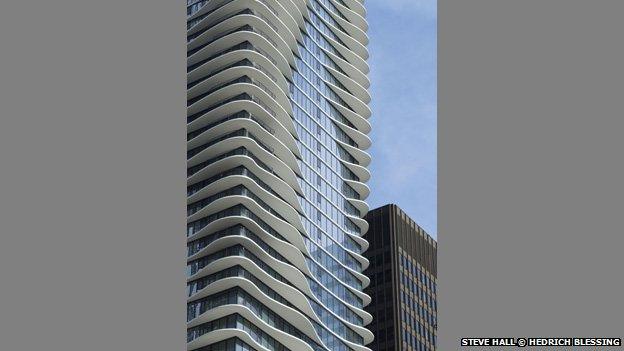

The Aqua Tower in Chicago used several types of glass designed to deter birds

A planned glass facade at the University of Waterloo, Canada, was replaced with murals

Shading at the US census complex in Maryland reduces both solar glare and reflection

Adhesive tape, external that is visible to birds can be stuck on windows but it is not widely available, while blinds and other shades can be expensive to install. New buildings can use a technique called fritting - a ceramic design baked into the glass which can be effective if the spaces between the patterns are the right size.

Until now, this has been applied to the interior surface of windows where it doesn't interfere with cleaning but is less effective at deterring birds than on the outside - that may soon change though as new methods are developed.

An alternative solution could be to use glass that emits UV signals that are more visible to birds than humans - Klem is positive about the only product to do this, Ornilux, but would like to see it developed further.

In some places, the law is adding another incentive - regulations were recently introduced in California and Minnesota requiring buildings in certain areas to be more bird-friendly. There is a similar law in Toronto.

Extra costs can be justified by designs that serve more than one purpose. Just as companies can save on energy bills by turning lights off at night, so they can save on air conditioning costs by using external shading that is visible to birds.

The Philadelphia based architectural firm KieranTimberlake which is building the new US embassy in London is designing an "outer envelope" for the building. This will provide shade, carry photovoltaic panels to generate solar energy, and help prevent bird collisions.

As new technologies are developed Michael Mesure from Flap is hoping designers will see this as an opportunity. "There are infinite things that you can do to the surface of a building that has its envelope made up of glass," he says. "The windows themselves can become an art form."

Videos by Colm O'Molloy, bird images courtesy of Sam Droege / US Geological Survey

Follow @BBCNewsMagazine, external on Twitter and on Facebook, external