Nutella: How the world went nuts for a hazelnut spread

- Published

Nutella, the nutty chocolate spread, is turning 50. Last year some 365 million kilos were consumed - roughly the weight of the Empire State Building - in 160 countries around the world. Half a century ago, in a small town in northern Italy, this would have been unimaginable.

In the hungry months after the end of World War Two, a young confectioner has a vision - of an affordable luxury made of a small amount of cocoa and lots of hazelnuts. His name: Pietro Ferrero.

"My grandfather lived to find this formula. He was completely obsessed by it," says the current boss of the family business, Giovanni Ferrero. "He woke up my grandmother at midnight - she was sleeping - and he made her taste it with spoons, asking, 'How was it?' and 'What do you think?'"

The way the family tells the story, it's a modern fairytale. Pietro was a humble man who lived in an enchanting region famed throughout the land for its delicious and abundant hazelnuts. Times were hard and chocolatey delights were not for the common people. Still, he dreamed of a magic formula that would enable everyone to enjoy his sweet treats.

There's a happy ending, too. Ferrero's tiny business in the picturesque town of Alba goes on to become the fourth most important international group in the chocolate confectionery market, with an annual turnover of more than 8bn euros (£6.5bn; $11bn).

When Pietro had his vision, the Piedmont region of Italy, and its capital Turin, was already famed for its chocolate industry. It was the birthplace of Gianduja, a creamy combination of chocolate and hazelnuts. But only the rich could think of buying it.

"Chocolate was so expensive, it was really high-end, nobody could afford it, at least in Italy," says Giovanni Ferrero.

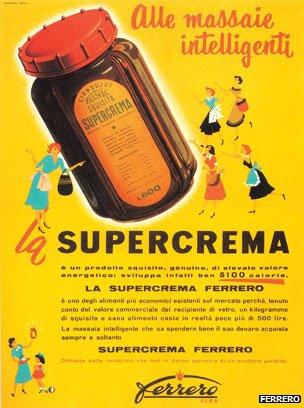

But in 1946 his grandfather launched Giandujot, or Pasta Gianduja. Produced as loaves wrapped in aluminium foil, it was a sort of solidified Nutella that had to be cut with a knife. The first spreadable version - Supercrema - came a few years later.

"This was a big success," says Giovanni. "It was the first brand that allowed people to enjoy confectionery at a very accessible price, even if it was not fully confectionery. This is how everything started."

Spreadability meant that a small amount went a long way, helping to break down the perception that chocolate was, as Giovanni puts it, "only for very special occasions and celebrations like Christmas and Easter".

It could also be eaten with bread, which formed a big part of the diet at the time. People who never ate chocolate got the Supercrema habit.

But it was Pietro's son, Michele Ferrero, who turned it into Nutella, relaunching it with its now famously secret recipe and iconic glass jar. His father was a man obsessed, says Giovanni, just like his grandfather.

"My father said, 'We can push it further, there are new technologies, there are new ways to integrate this winning recipe,'" he says.

"Nutella was born the same year as I was born, 1964, so I have a small brother in the family! And it was not just an Italian success but a European success."

The Italian post office has marked the anniversary with a stamp

The name gave the product instant international appeal. It said nuts. It also said Italy - "-ella" being a common affectionate or diminutive ending in Italian, as in mozzarella (cheese), tagliatella (a form of pasta), or caramella (Italian for a sweet).

Fifty years on, Nutella is a global phenomenon, produced in 11 factories worldwide, and accounting for one fifth of the Ferrero Group's turnover, along with other products such as Kinder and Ferrero Rocher chocolates. The company is the number one user of hazelnuts in the world, buying up 25% of the entire world production.

But how did one brand of hazelnut chocolate spread manage to creep its way into so many kitchen cupboards for a full five decades?

Roberta Sassatelli, associate professor of cultural sociology at Milan University and author of Consumer Culture, says initially Nutella was the epitome of a "pop lux" (popular luxury) for Italians.

"Nutella was something above average, something which was not a necessity," she says.

"It was something very sweet and modern and different from the classic sweets in Italy… So, to Italians it meant both modernity and the possibility of giving yourself a treat."

Both characteristics are embodied in its glass jar, with a "traditional and luxurious" shape, yet a plastic cap that is "modern, cheap and functional".

The marketing of Nutella, Sassatelli says, has been a triumph.

"They never sold it as a surrogate, and this was very clever. They could have played on different universal values like, 'This is cheap, this is affordable, this can substitute chocolate.' No, they played upon,'This is natural, it contains nuts so it's better than those that don't contain them.'"

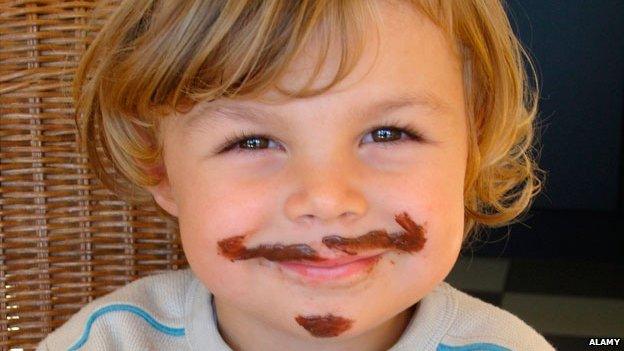

The images used to sell Nutella have tended to relate to children and family, she says - it may be an indulgence, but it's presented as the opposite of dangerous or decadent.

"It allows you little forms of transgression. It's a spread so you can dirty yourself a bit, but it's just for fun. I think that in the course of the history of Nutella, this is something which has been played on a lot - Nutella as a 'polite transgression'."

The company has been particularly good at marketing Nutella as a good ingredient for a nutritious breakfast, Sassatelli says, emphasising the hazelnuts and milk rather than the high content of sugar and saturated fat. It is in fact nearly 57% sugar and 32% fat - and about a third of the fat is saturated.

"We all want our kids to have a balanced breakfast," said an advertisement in the UK in 2008, adding that each 400g jar contained 52 hazelnuts, the equivalent of a glass of skimmed milk and some cocoa. The Advertising Standards Authority (ASA) ruled it exaggerated the spread's nutritional value.

But three years later, the ASA gave a clean bill of health to another ad urging people to "Wake up to Nutella", and continuing: "Each 15g portion contains two whole hazelnuts, some skimmed milk and cocoa."

As a child, Giovanni Ferrero was allowed Nutella for breakfast

Nutella's three-year sponsorship of the national football team, starting in 1998, was a masterstroke, Sassatelli says.

"On the one hand, this links Nutella with the Italian national sentiment. On the other hand, of course, it links it with the idea that, in the right quantities, it is healthy to the point that even athletes use it."

Health issues will be far from the minds of Nutella fans taking part in this weekend's 50th birthday celebrations, which include a street party on Saturday in Ferrero's home town of Alba and a free concert on Sunday featuring pop star Mika in Naples' Piazza del Plebiscito.

Among passionate fans celebrating Nutella's half century (and his own) is, of course, Giovanni Ferrero, although he admits its precise birthday is something of a mystery.

"Legend tells us that the first jar was manufactured out of the factory 50 years ago on 20 April and the first act of consumption was the 18 May," he says. "But there's no scientific evidence!"

He says he loves not only the taste, but also the "sweet memories" of his childhood. His parents allowed him to eat Nutella at breakfast, and he now allows his own two sons to do the same.

The Ferreros, he says, are a family with an "intergenerational sweet tooth".