Halfpenny: The story of how a tiny, 'annoying' coin was abolished

- Published

It's 30 years since the British decimal halfpenny was being phased out. Why did the UK hang on to a tiny coin for so long?

Before everyone gets misty-eyed about the bronze halfpenny, it's worth remembering how annoying Britain's least loved coin, notorious for getting lost in trousers and furniture upholstery, was.

People were commonly said not to bother to bend down in the street to pick it up if they dropped one.

"In terms of the coins in your pocket, it's useless," the National Consumer Council told the Herald Tribune in 1983. News stand workers in the early 1980s couldn't even give the unloved halfpenny away, according to the paper. "We've got a bagful in the till, and although customers give them to us in payments sometimes, we can't hand any out," vendor Danny Curbishley complained.

The coin's pifflingness - or necessity - was regular fodder for the Times' letter pages. "Sir, I can scarcely believe that writers of letters bemoaning the demise of the halfpenny coin, because they would not be able to deal with some small-apertured possession without it, are being serious," wrote Pamela Johnson in February 1984.

"Sir, Some may dispute the 'rounding-up' or down, of the halfpenny coin, but let not its existence be imperilled. It is indispensable for levelling off pendulum clocks," countered Priscilla Glover in December.

The then Chancellor Nigel Lawson announced the coin's demise in a written Commons answer in 1984, saying "most people would be glad to get rid of them". The Royal Mint stopped making them at the end of February, and it ceased to be legal tender in December.

But the curious thing about the coin is not that it was abolished, rather that it lasted a full 13 years after its introduction with decimalisation in 1971.

The Treasury's delay in ending the halfpenny arose from fears that if the coin was abolished, retailers would raise prices to the nearest penny, which would in turn contribute to inflation. By 1984, the government had got to a point where it believed so few transactions would be affected, there would be no measurable impact.

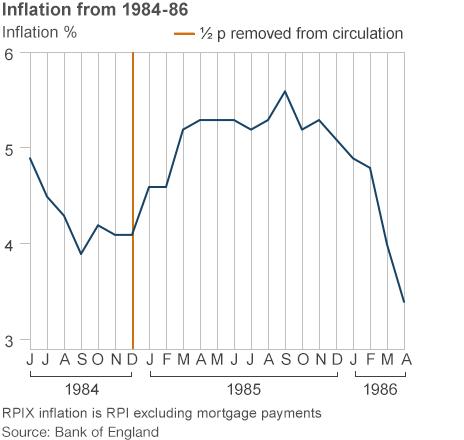

When it came down to it, Bank of England figures show inflation rose by 0.5% in January 1985. But accounts at the Bank in the subsequent months did not make mention of the removal of the halfpenny as a reason. A spokesman today says inflation was more likely to be down to a decline in exchange rates or a rise in commodity prices.

Dr Kevin Clancy, director of the Royal Mint Museum, agrees that it is "profoundly unlikely" that the coin's withdrawal had any impact on inflation. "If you think of how many transactions occurred in 1984, the idea that the lowest denomination in British currency had an impact is extremely unlikely. There were far many bigger economic influences at play. The same questions were raised with decimalisation, and that was a whole system, not one coin. The conclusion was even if retailers did adjust their prices by rounding up, the impact would be negligible in the economy of the nation."

A study - albeit rather unscientific - of the price of a couple of items suggests fears all prices would be rounded up didn't materialise. The second class stamp rose from 12.5p in 1983 to 13p in 1984, then dropped to 12p in 1985. The price of a dog licence went from 37.5p in 1984 to 37p in 1985.

And supermarket chains pledged to round prices down rather than up.

Nigel Lawson: The chancellor who abolished the halfpenny

Apart from annoyance to ordinary people, the reasons for getting rid of the coin were compelling.

"High inflation in the late 1970s had devalued the coin to the point that it was insignificant and costly to produce," says the British Museum's modern money curator Thomas Hockenhull. "By 1984, it had an impractically small value and purchasing power."

At the time, there was speculation the coin had become more expensive to make than its face value. Garrick Hileman, an economic historian at the London School of Economics, says the history of currency is littered with cases of when melted coins may have exceeded their purchasing power.

Size was another sticking point. The halfpenny was tiny - about 17mm diameter compared with the current penny's 20mm - and critics complained many fell out of pockets and got stuck behind sofas.

Research shows the optimum size of a coin is between 19mm-22mm, according to Clancey. "17mm is still fine - anything between 15mm and 28mm is practical - but it's at the lower end. At the other end of the scale the British crown [in 1707] was 38mm and was never popular," he says.

The halfpenny also had an image problem because it wasn't very aesthetically pleasing as well, according to Hockenhull.

"It didn't have the Royal Coat of Arms like the pound coin, an image of Britannia or the ship of the pre-decimal halfpenny. It was a boring looking coin - not one I can't imagine anyone thinking beautiful. It also didn't symbolise a national identity. The halfpenny was always a part of a penny, never its own entity. Back in the 1300s they used to literally cut pennies in half to get halfpennies, or quarters for a farthing," he says.

But having killed the halfpenny, why has the UK never done something about the penny? Hileman says the story of the halfpenny fits into a broader question over "the big problem of small change".

"There's an economic impact to having fewer denominations - it can create friction when the denomination isn't micro enough to accommodate the transactions people want to do. But the halfpenny fits into a historical problem of what happens to currency when it's not as efficient as it could be - in most cases it comes down to the cost it takes to produce versus its economic utility," he says.

The Canadian penny was withdrawn from circulation last year because production costs exceeded its monetary value. There has been a long-running debate in the US over the future of its single cent and the future of the British penny has been questioned.

In 1984, not many people mourned the loss of the halfpenny. "The decimal halfpenny didn't have a long history. It was never top of the bill or had a starring role," says Clancy. But he says to dismiss the coin's value entirely would do it a disservice.

"The halfpenny played an important role in the important transition to a new currency system. It was a point of familiarity. A way of reassuring people things hadn't changed too much," he says.

Follow @BBCNewsMagazine, external on Twitter and on Facebook, external