Punished by axe: Bonded labour in India's brick kilns

- Published

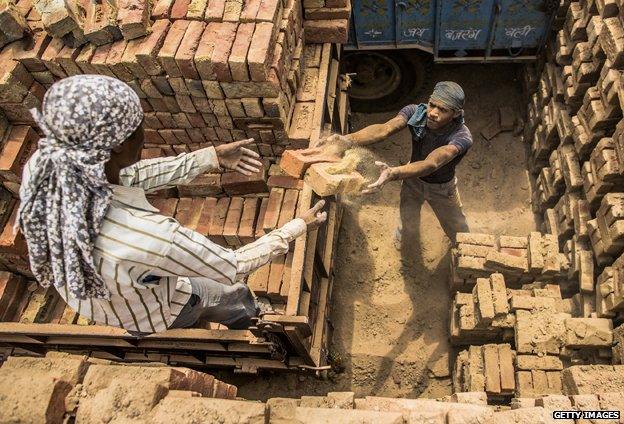

India's economy is the 10th largest in the world, but millions of the country's workers are thought to be held in conditions little better than slavery. One man's story - which some may find disturbing - illustrates the extreme violence that some labourers are subjected to.

Dialu Nial's life changed forever when he was held down by his neck in a forest and one of his kidnappers raised an axe to strike.

He was asked if he wanted to lose his life, a leg or a hand.

Six days earlier, Nial had been among 12 young men being taken against their will to make bricks on the outskirts of one of India's biggest cities, Hyderabad.

During the journey, they got a chance to escape and ran for it - but Nial and a friend were caught and this was their punishment.

Both chose to lose their right hands. Nial had to watch while the other man's hand was cut first.

"They put his arm on a rock. One held his neck and two held his arm. Another brought down the axe and severed his hand just like a chicken's head. Then they cut mine.

"The pain was terrible. I thought I was going to die," says Nial.

Now free, and his injury healing, he is back home deep in the countryside of Orissa. There is no electricity or sanitation. Many of the villagers are illiterate.

"I didn't go to school. When I was a child I tended cattle and harvested rice," Nial says, sitting on the earth outside the cluster of huts which are his family's home.

It is from communities like this that people are liable to be drawn into a system known as bonded labour. Typically a broker finds someone a job and charges a fee that they will repay by working - but their wages are so low that it takes years, or even a whole lifetime. Meanwhile, violence keeps them in line.

Activists and academics estimate that some 10 million bonded labourers are working in India's key industries, indirectly contributing to the profits of global Indian brands and multinationals that operate in the country and have helped to transform India into an economic powerhouse.

Laid out beside Nial are a number of old plastic sacks. His family ekes out a living by unravelling them and turning the individual threads into binding cord. Awkwardly, Nial wedges a wooden spool of thread between his toes, and holds another in his remaining hand. His brother, Rahaso, sits next to him doing the same.

Nial struggles to wind the cord, his brow creasing. His brother works quickly, outpacing him. Then the spool flips out of Nial's hand. Rahaso gives it back him. Disappointment and anger flood through Nial's face.

It was in early December that Nilamber, a friend from a nearby village told Nial about a job in brick kiln for which he would supposedly get 10,000 rupees ($165; £98) up front. It was all being organised by one of Nilamber's neighbours, Bimal, who was trying out working as a broker.

Nial, Nilamber, Bimal, and 10 others travelled by bus to meet the main contractor.

"I knew he was a rich man. He had a motorcycle and wore a tie," says Nial.

The contractor showed them the money, but took it straight back. They would not in fact get it up front, he said, but some time later. Nial nonetheless believed he would still be paid and agreed to work - although illegal, it meant he had technically taken the bond.

The men were taken the next day to the railway station at Raipur, the capital of Chhattisgargh state. Then, instead of being sent on a short journey to a brick kiln as they had been promised, they discovered the train was heading 500 miles (800km) south to Hyderabad, a thriving city and a pillar of India's economic success. But some in the group had already heard stories about forced labour there, and got ready to rebel.

When the train stopped at a station, all except Nial and Nilamber escaped. Instead of continuing to Hyderabad the contractor took them back to Raipur, spending some of the journey on his mobile phone, arranging their reception.

"His henchmen were waiting for us," recalls Nial. "They held us and put their hands over our mouths to stop us shouting."

At this point, Bimal slipped away. Nial and Nilamber were taken back to the contractor's house and held hostage.

"They called our families telling them to pay money for our release," says Nial. "They beat us hard so my brother could hear me crying in pain down the phone."

The contractor demanded that Nial pay him 20,000 rupees (US$330; £196) for his release but his family was unable to raise the money. He and Nilamber were held for five days. During the day they were made to work on the contractor's farm. In the evenings they were beaten.

On the sixth day, his kidnappers were drinking heavily. The contractor and five of his men drove them to remote woodland. First they were held down and beaten. Then, they were made to kneel - and mutilated.

"They threw my hand into the woods," he says. "I wrapped my left hand around my wound and held it tight. I squeezed it to stop the bleeding until the pain became too much and I released it. Then I had to grip it again."

A basic survival instinct took over. They followed a stream to a village, where they were able to bind their wounds and cover them with a plastic bag. Then they took a bus to a nearby town to seek hospital treatment.

Nial stiffens as he tells the story. Often he stops to gather his thoughts.

He has now begun a two-year programme run by a charity, the International Justice Mission (IJM), to help him recover from his ordeal. As part of his rehabilitation, he joins a group of more than 150 people at a counselling session in Orissa - all of whom have been freed from bonded labour in the past few months, mostly in brick kilns.

Among them are dozens of children. Most of the men have been badly beaten. There are women who have been raped, and two who were kicked in the stomach while pregnant - the husband of one was thrown to his death from a train.

Roseann Rajan from International Justice Mission helps free people from bonded labour

In a scene reminiscent of the era of slavery in the US, they sing about their troubles: "We will overcome our pain. We will be free," goes the chorus.

For everyone, the first year of the programme is about re-learning how to express the most basic of human emotions.

"They have been bought and traded as property and that is how they see themselves," explains Roseann Rajan, a counsellor with IJM. "They don't know how to show emotions. They can't smile or frown or express grief."

Activists argue that the Indian government's failure to protect people from forced labour, kidnapping, and other crimes amounts to a serious abuse of citizens' rights.

"There are deep-rooted problems of business-related human rights abuse in India," says Peter Frankental, Economic Relations Programme Director of Amnesty International UK. "Much of that involves the way business is conducted, an unwillingness to enforce laws against companies, and fabricated charges and false imprisonment against activists who try to bring these issues to light."

Each Indian brick kiln moulds a unique logo on to its bricks

The Confederation of Indian Industries instructs companies to follow Indian law, which has banned bonded labour since 1976. But the IJM says the courts do little to punish those who break the law, as it takes about five years to bring a case to court and even then a broker or brick kiln owner often gets away with a $30 (£18) fine.

Under UN guidelines introduced in 2011, multinationals operating in India also bear responsibility for any abuse of workers all the way down their supply chains. Most say they are fully committed to upholding human rights and the UN guidelines. But campaigners say they know of no big company operating in India that guarantees its buildings are constructed from legally-made bricks. Because each brick kiln moulds a unique logo on to its bricks, it would be possible to trace them back to their origins.

Slavery in the supply chain

Britain's biggest trade union, Unite, describes the use of bonded labour in India as a scandal - and says it will start monitoring companies that might be using slavery in their supply chains. "It's been going on for too long and must stop now," says general secretary Len McCluskey.

Britain encourages companies to invest in India - it has launched a record £1bn ($1.7bn) credit line for those involved in Indian infrastructure contracts - but advises them to incorporate human rights protection into their operations.

The International Labour Organisation (ILO) last month introduced a tough, legally-binding protocol against forced labour, saying it was an "an abomination which still afflicts our world of work". Its 185 member states will incorporate the protocol into their national laws.

Many in government, meanwhile, deny that bonded labour exists.

The Labour Commissioner for Andra Pradesh - the state of which Hyderabad is the capital - told me in December he could give me a 100% guarantee that there was no bonded labour on his territory.

"There's no such thing," said Dr A Ashok.

He cited the brick kilns in Ranga Reddy just outside Hyderabad as a model for the industry. But many of those on Nial's rehabilitation programme have just come from there. Each has a government-stamped certificate stating they have been freed from bonded labour.

Unusually, arrests have been made in connection with Nial's kidnapping and the suspects are in custody. Bimal, the villager who first recruited them, was arrested and has been released on bail.

Bimal says he would like to apologise to Nial

We find him walking through flat scrubland, peppered with trees, past broken fences and wooden huts. Married with two children, and six years older than Nial, he carries himself with far more confidence.

It's true he recruited Nial, he says, but he denies any involvement in kidnappings and beatings.

"It wasn't only my mistake - we all made the decision to go. I want to apologise and meet Dialu [Nial] again so we can live together as neighbours," says Bimal.

Nial, though, rejects any idea of reconciliation. "Jail isn't good enough for them. They should be hanged," he says.

His hopes for the future? "I really want to get married and have a family of my own."

But with that, his face darkens again. He glances down and covers his stump with his shirt sleeve. In his culture, with his severed hand, finding a wife and starting a family will be very difficult indeed.

He shakes his head sadly. "Of course, I can never forgive them."

Photographs by Dominic Hurst

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.