Nightmare neighbours: behind the chic facades of French apartment blocks

- Published

Neighbours' Day happens every May across France. It is a time for people to make peace with the people next door. But in the apartment blocks of Paris, bitterness and hostility are thriving.

The people upstairs are having breakfast. I know because there is a particular scraping of chairs and the blunt thud of slippered feet crossing to and fro from kitchen to dining room. He talks, she hums. A pause. They must be pouring the coffee.

Our apartment building, like many in Paris, dates from the late 19th Century. The floors are echoing, antique parquet and there is absolutely no sound insulation.

A sneeze on the fourth floor can be heard on the second.

My neighbour, Madame Joliot, an unabashed television addict, is bemused.

"It is strange," she says. "In all those American soaps, the neighbours are lovely. Helpful, chatty, kind, romantic. But when I watch Nos Chers Voisins - well, that's France!"

The sitcom Nos Chers Voisins, or Our Dear Neighbours, reflects the real-life tensions of apartment living

Madame Joliot and several million other French tune in each evening to watch Our Dear Neighbours, the cult TV comedy series of everyday life in a fictional apartment block.

It gives the perfect "front-door spy hole" view of what goes on amongst the neighbours.

Brief encounters in the hallway, conversations in the lift, little incidents in the courtyard - all the tensions, intrigues, scheming rivalries and absurd pettiness of communal French living are revealed.

Madame Joliot herself is caught in the usual tangled web of inter-neighbour dispute.

There is the woman on the floor below who cannot abide Madame Joliot's flowering terraces because, from time to time, leaves blow onto her balcony.

Complaints ensue - formal letters are sent by registered post, threatening legal action unless Madame Joliot personally vacuums the few leaves, with her own vacuum cleaner, whenever they might fall.

On the second floor, the daughter of the building's owner throws deafening all-night parties with dismaying regularity but no-one dares complain lest there be trouble with the lease.

If, however, Madame Joliot's pet dog barks even once in the courtyard in the middle of a weekday, there is hell to pay.

Just above, there is a lady with stilettos - extraordinarily loud when heard through the ceiling. Madame Joliot complained, fountain pen on elegant visiting card duly slipped under doorway.

The reply, a typed letter, sent by registered post, copied to a solicitor, read: "Madame, I have restored and polished my parquet and I have no intention of ruining the effect with rugs just for your benefit."

Leaves, heels and parties are one thing. Vandalism as revenge is quite another and yet, it is relatively common.

Madame Grelois, 72, has lived in the same building in Saint Germain for the last 50 years and raised her children and now her grandchildren there.

"Pushchairs, prams, there is always a problem," she says. "There are mountains of rules but it makes no difference.

"The number of pushchairs that are vandalised - deliberately ruined - when they are left neatly and correctly in the hallway!

"My first baby's pram was slashed so I had to lug it down the cellar steps each night and up again each morning."

With much of Paris living between 19th century walls and floors, it is clear that disturbances between neighbours cannot be anything new.

The writer, Marcel Proust, had his bedroom lined with cork to deaden the noise but it was not entirely successful as a new volume of letters, just published, reveals.

Letters to His Neighbour is a collection of notes written by Proust to his upstairs neighbour, Madame Williams - an accomplished harpist - and her husband, an American dentist whose consulting room was directly above Proust's bedroom.

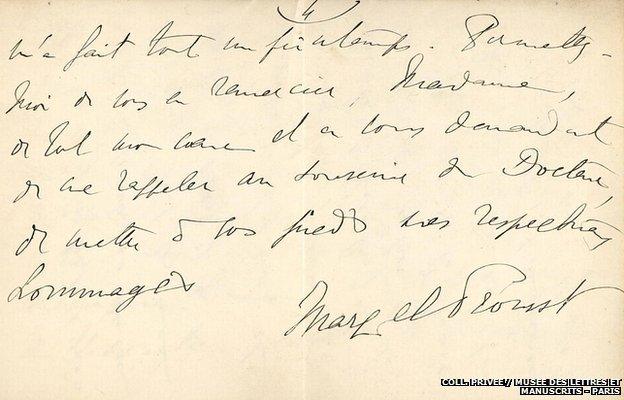

This note from Proust reads: "Allow me to thank you Madame, from the bottom of my heart and ask you to convey my regards to the doctor while laying my respectful homage at your feet"

The dental drill with its rudimentary electric motor sent an unfortunate din through the cork-lined ceiling and into Proust's head - which was trying to concentrate as he composed his complex masterpiece, In Search of Lost Time.

The letters are, of course, exquisitely written and elevate the form of notes-between-neighbours from the depths of the rude and banal to the heights of poetry, wit and grace.

Proust and Madame Williams became intimate friends through their correspondence and Proust's polite requests for silence on certain days and at certain times are put with a delicacy and charm that even the most heartless neighbour could not refuse.

The letters have caused some reflection amongst residents of the more self-consciously intellectual areas of the city and - if the local gossips are to be believed - neighbourly correspondence is once again aspiring to literary art amongst the streets of Montparnasse.

"Veuillez agreer, Madame, ma reconnaissance pour votre charitable souci de mon repos…"

"Madame, with my grateful recognition of your charitable concern for my repose and my greatest respectful gratitude, I am yours, very faithfully, Marcel Proust."

Ah, those were the days.

How to listen to From Our Own Correspondent, external:

BBC Radio 4: Saturdays at 11:30 and some Thursdays at 11:00

Listen online or download the podcast.

BBC World Service: Short editions Monday-Friday - see World Service programme schedule.

Follow @BBCNewsMagazine, external on Twitter and on Facebook, external