The brave new world of DIY faecal transplant

- Published

You would have to be desperate to take a sample of your husband's excrement, liquidise it in a kitchen blender and then insert it into your body with an off-the-shelf enema kit. This article contains images and descriptions which some might find shocking.

In April 2012, Catherine Duff was ready to try anything. She was wasting away with crippling abdominal pains, nausea, vomiting and diarrhoea so severe she was confined to the house. At 56, in the US state of Indiana, she had come down with her sixth Clostridium difficile infection in six years.

"My colorectal surgeon said: 'The easiest thing would be to just take your colon out.' And my question was: 'Easier for whom?'"

Appalled at the idea of losing her large intestine, Duff's family feverishly searched for alternative treatments on the internet. One of them turned up an article about a doctor in Australia, Thomas Borody, who had been treating C. diff with an unusual process known as faecal transplant, or faecal microbiota transplantation (FMT).

Clostridium difficile is an obnoxious microbe, usually kept in check by other bacteria in our guts. Problems arise when antibiotics remove some of these "friendly" bacteria, allowing C. diff to take over. One doctor compares it to the hooligan on the bus who is prevented from doing any harm by the sheer number of people on board. A course of antibiotics is equivalent to some of these people getting off at a stop, allowing the hooligan to run wild. About 50% of a person's faeces is bacteria, and a faecal transplant is like a whole new busload of people - the friendly bacteria - being hustled on board.

John and Catherine Duff

It's an emerging, but not new treatment. Chinese medicine has recommended swallowing small doses of faecal matter for some ailments for 1,500 years. It's also a treatment option in veterinary medicine. In 1958, a Denver surgeon, Ben Eiseman, used faecal transplants to treat an inflammation of the colon. He wrote the procedure up in a journal article, which, years later, inspired Thomas Borody to try the radical treatment on patients with C. diff. Now the head of the Centre for Digestive Diseases in New South Wales, Borody has recorded some striking successes.

Duff showed the article about Borody to her gastroenterologist, her infectious diseases consultant and her colorectal surgeon. But none of them had performed a faecal transplant and none was willing to try. When Duff said that she intended to administer the treatment herself with her husband's faeces, the gastroenterologist agreed to send a sample away to be screened for disease.

After they received the all-clear to use the stool, it was Duff's husband John that donned plastic gloves and assiduously followed the instructions they found online. He was no doctor, but as a retired submarine commander Duff considered him equal to the task.

"He was in the habit of spending months at a time in a metal tube with over 100 men," Duff says. "As a result, nothing grosses him out. So he was the one that made the donation, and then mixed it in a blender with saline, and then he gave it to me in an enema.

"My husband kissed me after I lay down and told me not to worry, that everything was going to be OK, and that it was going to work."

Then he threw away the blender.

Duff lay on her back with her legs in the air, trying to hold the foreign material in her body. She lasted four hours before needing to go to the toilet. They started the process at 16:00 in the afternoon. By 22:00 that night she felt almost completely better. "And I had been literally dying the day before," she says. "I was going into renal failure - I was dying."

Lots of people die from Clostridium difficile. In the US, the figure is estimated by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to be 14,000 per year, while in England and Wales, 1,646 deaths from C. diff were recorded in 2012.

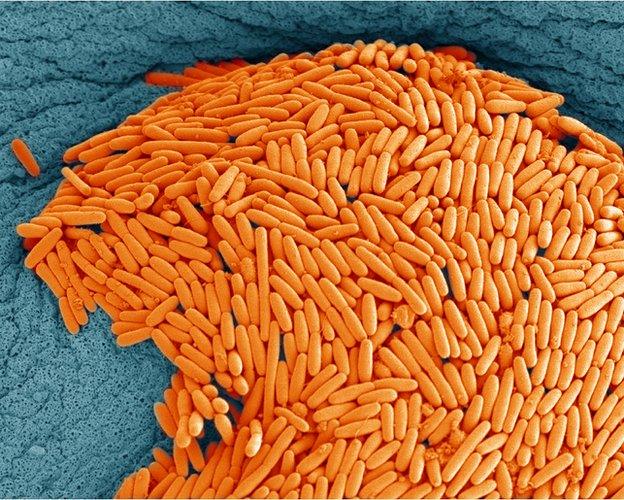

A colony of C. diff grown on an agar plate

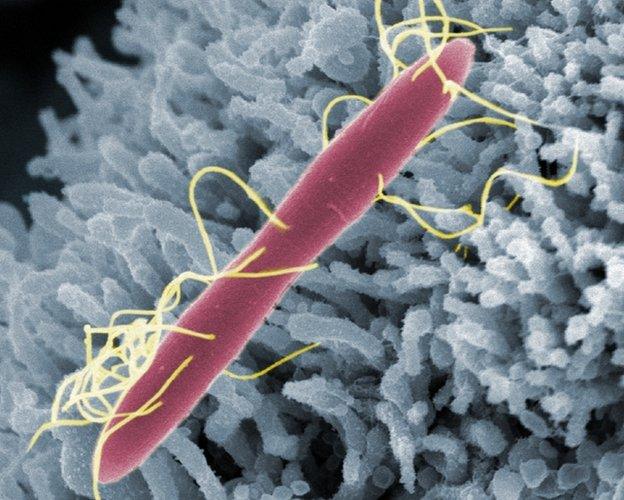

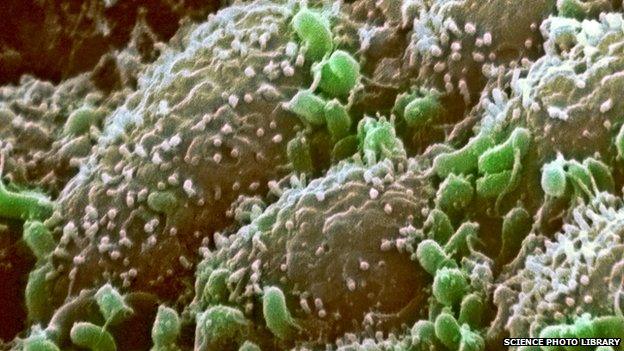

A C. diff cell colonising the microvilli on a mouse's intestinal cell

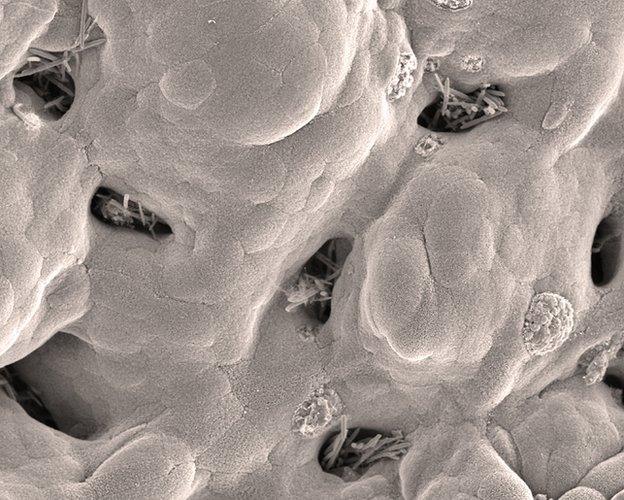

C. diff colonising a mouse's intestine

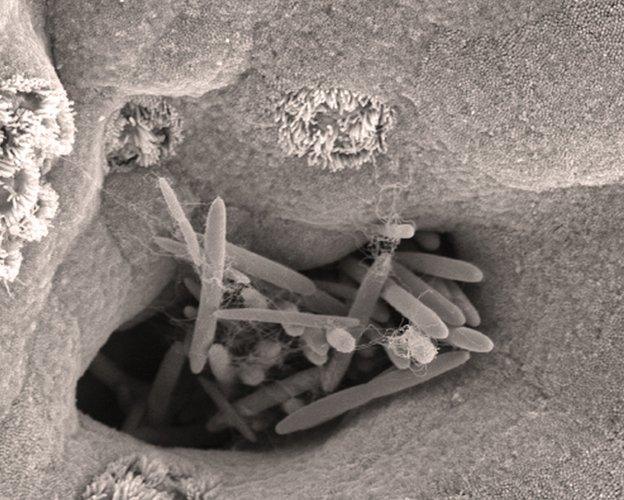

C. diff colonising a crypt in a mouse's intestine

Even though antibiotics cause the disease, most patients are cured by more antibiotics. But for some, the problem returns after every course of drugs, as it did for Catherine Duff.

There is growing recognition that faecal transplant is the best way to treat patients like these. In the first randomised trial of the technique, external published in the New England Journal of Medicine last year, 94% of patients were cured by the treatment, whereas a course of antibiotics cured just 27%. The disparity was so huge that the researchers stopped the trial early, on the grounds that it was unethical to deny the better cure to the cohort assigned antibiotics.

Dozens of other trials involving faecal transplants are either in progress or have recently been completed. Dr Ilan Youngster was one of the authors of a pilot study, published in April in the journal Clinical Infectious Diseases, which found that using frozen faecal samples, administered "top-down" through a tube in the nose, was as effective as using fresh samples in a "bottom-up" procedure.

Youngster admits that even when frozen, faeces have a slight smell. "It's not a very pleasant treatment, especially from a psychological point of view," he says. "But we have yet to encounter a sick person with C. diff who has refused this treatment. It's a horrible disease. We had a patient with cancer that contracted C. diff and he said 'If I could get rid of one of these two diseases, please get rid of the C. diff.'"

Frozen faecal matter in Dr Youngster's trial at Massachusetts General Hospital

In the US, the FDA (Food and Drug Administration) has puzzled over how to regulate faecal transplant, but some doctors do offer the treatment, usually by colonoscopy. Catherine Duff, who set up the patient advocacy group the Fecal Transplant Foundation at the beginning of 2013, originally listed 19 providers on her website. Now there are about 75.

But she says that's nowhere near enough and people are dying because there is no provider close to their home. "Even if those doctors did nothing but faecal transplant, 24 hours a day, seven days a week, they couldn't meet the need," she says.

Dr Alexander Khoruts at the University of Minnesota says clinics are concerned that offering faecal transplant could scare other patients away, as the smell is unmistakeable. "Imagine blending stool in a clinic space - the aesthetic problems with that are not trivial. When you click on the 'blend' button and the surface area of that faecal material increases thousands of folds in a matter of seconds, it is quite potent."

The difficulty of getting to a clinic that offers faecal transplant and abundant availability of free faeces explains why many continue to opt for what Duff and her husband did in 2012 - a self-administered transplant. She estimates that for every procedure that takes place in a clinic, scores more occur in bedrooms and bathrooms around the US.

A website, The Power of Poop, is full of tips and personal stories to help people with their first at-home faecal transplant, and a Facebook group under the name Sally Brown shares advice from patients who have immersed themselves in the science of gut microbiota.

Alongside the science there is humour, and Duff's Fecal Transplant Foundation is planning to bring out a range of merchandise including sweatshirts, beverage holders, baseball caps and bumper stickers with "unique and possibly hysterically funny slogans" alongside the foundation's awareness-raising brown ribbon.

Most DIY faecal transplant patients are, in fact, not suffering from C. diff, but from a range of other diseases that they believe the procedure will help, and which doctors are not willing or allowed to treat with faecal transplant. They include conditions that would appear to have very little to do with gut bacteria - including MS, autism, and diabetes - but the most common ailments treated are the inflammatory bowel diseases Crohn's and ulcerative colitis.

The efficacy of faecal transplant on these diseases - which around 1.5 million people suffer from in the US - is uncertain. Dr Elaine Petrof, an infectious diseases specialist at Kingston General Hospital, Ontario, says that for C. diff sufferers, taking antibiotics is like throwing gasoline on a weed-ridden lawn. "What you've done is you've killed the weeds but you've also killed the grass. So you're now left with a charred, barren, destroyed piece of land and you have to put seeds back on there to get stuff to grow again or the else the weeds will just come back."

She goes on: "With Crohn's disease it's different. Now you're dealing with another garden full of weeds, if you like. So then you're trying to replace a bad ecosystem that's already taken hold with another ecosystem. That's got to be much trickier and more difficult to accomplish."

Gut bacteria - five astonishing facts

90% of cells in our body are bacteria - organically, our bodies are only 10% human

We are less than 1% human in terms of the overall gene activity in our bodies

Babies are born sterile, but 50% become carriers of C. diff in their first year of life - other bacteria hold it in check

One strain of bacteria, marketed as the probiotic Mutaflor, is reportedly from a culture taken from the stomach of a German soldier in WW1 - he was apparently the only one in his barracks not to succumb to food poisoning

Jeremy Nicholson at Imperial College London says that developed nations have probably changed their microbial communities more in the last 50 years than in the previous 10,000, thanks to antibiotics and other lifestyle changes

In 2006, on the very day her husband died from lung cancer, Sky Curtis found herself sitting with her 18-year-old son in a doctor's waiting room in Toronto. He was curled up in a ball in pain, with bloody diarrhoea, a fever, cankers in his mouth, a rash on his face and boils on his legs. He was later diagnosed with ulcerative colitis and informed that his colon would have to be removed.

Like Catherine Duff, Curtis searched for alternative medicines and came across Thomas Borody in Australia. She gave him a call. "He talked to me for hours at a time," she says. "The man is a saint."

Curtis found a local doctor who was willing to prescribe a series of drugs which Borody recommended. Her son went into remission, but later fell sick again, with a new diagnosis of Crohn's. With her son wasting away in front of her eyes, she called Borody again and he suggested a faecal transplant.

"I decided, after hemming and hawing and talking to my son, that yes, he would let me put poo up his bum to see if that would work," she recalls. She had a sample of her own stool screened and they performed their first transplant on Christmas Day, 2008. "I kept thinking, 'I'm giving my kid a bag of [faeces] for Christmas. It wasn't ideal, but he was just so sick and I knew if I waited until after the Christmas holidays he would be dead."

The first few transplants, Curtis says, "sort-of worked". She then toyed with Borody's protocol, and on the basis of personal research into her son's condition, changed the frequency of the transplants and gave him painkillers, anti-inflammatory drugs, sedatives and steroid creams. Bit by bit, he got better.

Curtis was left from this ordeal with material for a memoir and her own protocol, developed through trial-and-error experiments with her son's treatment. This became a handbook that is now one of the key works in the DIY faecal transplant community.

Curtis's story is an inspiration to many, but the impact of faecal transplant on inflammatory bowel diseases is unpredictable, and varies from patient to patient. Unlike Curtis's son, some find they have to continue performing transplants to sustain their health. A team at Mount Sinai Hospital in New York hopes to start a study soon identifying the subgroups of patients that will potentially benefit from the treatment.

"We have to prove the science," says Dr Ashish Atreja from the hospital. "Because if we can't prove the science really works then we are creating an optimism which is not genuine."

Curtis says she has had plenty of people thanking her for her book, and so far, no feedback from disappointed patients, or criticism from doctors. Advocates of faecal transplant insist that it is safe, and point out that there are no published reports of anyone becoming ill as a result of the procedure. "It's about as dangerous as changing a baby's diaper," says Curtis.

Dr Lawrence Brandt at Montefiore Medical Center in New York, one of the first advocates of the procedure in the US, agrees that the administration of stool in an enema is reasonably safe, but he worries that some people may be doing it before other treatment options have been explored, or after a faulty diagnosis.

Ilan Youngster agrees. "We wouldn't want anyone out there getting a stool transplant just because they feel they would benefit from it," he says.

A bigger concern is that they are using untested stool. At Brandt's clinic, donors are screened for a long list of infectious diseases, including HIV and hepatitis, and are subjected to a battery of questions about their lifestyle and habits. Donors with allergies and heart disease are excluded, as well those who have recently taken antibiotics.

"We had one woman who said: 'Can I use my dog's stool?'" says Brandt. "I'm sure that there are some people out there who are saying, 'Well, I have a horse. He's pretty healthy and he has an adequate supply of stool - I'll use his stool." But using animal stool is absolutely not recommended.

Curtis, like all faecal transplant advocates, agrees that it is vital to get stool samples tested, but says that unfortunately only a few per cent of at-home patients do this.

For many patients, the choice of donor is often about more than just choosing someone with healthy stool, she says. "It is important that the donor feels psychologically 'right' because their poo is going into the sick person's body." In the online faecal transplant community, patients occasionally refer to their donors as "poop angels".

In November 2011, Edward Bondurant had a "very strange conversation" with a friend he had known since he was five. "I just said well, you have something that you do every day that might change my life. I knew this person better than my brother but I still felt odd asking - but he immediately said yes."

Edward says he often reads the BBC News website while carrying out a faecal transplant

Bondurant has suffered with ulcerative colitis since 1978, on and off. When it flares up, he says, "you need to be 10 steps from the bathroom - and sometimes that's two steps too many". The drugs he takes for it are expensive - around $11,000 (£6,500) a dose - and have bad side-effects.

Bondurant's first attempt at faecal transplant was a messy disaster but he is now something of a pro, able to do his job as a financial adviser while adopting the best positions needed for the faecal matter to slip into his colon. "I have actually had long conversations, doing large business deals for large sums of money, while hanging upside down," he says.

Although Bondurant still takes drugs when his colitis flares up, he does regular faecal transplants to keep the disease at bay - he has now done more than 100. He can adapt his schedule to his donor's body clock. He only lives five blocks away, so Bondurant either swings by his house, or his donor, letting himself into Bondurant's house with his own key, drops off his droppings, leaving them in Tupperware in his fridge.

Faecal deposits being processed at OpenBiome

But there is no medical reason why you need to be best friends with your faecal donor. At the beginning of 2013, two friends at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology started OpenBiome, a non-profit making stool bank. Deposits from three fully-screened donors are kept in 250ml bottles at -80C, before being shipped to hospitals for $250 (£150) each. A frozen stool bank gets around the logistical problems of handling fresh faeces, and the time delay involved in screening new donors. So far, 370 little bottles have been sent to 39 hospitals.

A recently proposed rule from the FDA, that donors should be known to the patient or the doctor administering the faecal transplant, threatens OpenBiome's business model, but the owners are still feeling upbeat about the future. Their latest venture is in capsules containing faeces. Similar products have been trialled successfully by researchers at the University of Calgary and Ilan Youngster is currently working on a further study. Thomas Borody also uses them - he calls them "crapsules". Taking faecal tablets, although still revolting as a concept, is less invasive than a colonoscopy or enema.

OpenBiome's prototype faecal capsule

A different vision of the future of the treatment is a move away from faeces altogether. Instead, patients would receive a live bacterial culture targeted to fight Clostridium difficile - in effect, a synthetic stool.

Although it would be developed from faecal samples, it would only need to contain a handful of strains of bacteria, not the hundreds present in excrement, which would make its impact on the human gut more reproducible and understandable.

Trevor Lawley at the Sanger Institute in the UK is down to just 18 strains in his synthetic stool. He is in the process of overcoming a series of technical problems, such as how to grow these anaerobic organisms and prevent them from evolving before they can be used. But he says the real challenge in the emerging field of "live biotherapeutics" is how to regulate it.

Meanwhile, in Canada Dr Petrof has already cured C. diff in two patients using a synthetic solution containing 33 strains of bacteria grown inside a "robogut"- an imitation colon.

Faecal transplant, she says, works. "But I'll be the first to admit it's crude. It's essentially like pouring sewage into people." Her synthetic stool, on the other hand, smells a lot less obnoxious and is a sterile-looking milky colour.

"It's still the same concept of using a microbial ecosystem or community of bacteria," says Petrof. "But we're just moving away from taking it out of the toilet."

A miniature Robogut in action - Petrof and her colleagues call their synthetic stool "RePOOPulate"

Ilan Youngster and Thomas Borody appeared on Health Check on the BBC World Service. Listen again on iPlayer or get the Health Check podcast.

Follow @BBCNewsMagazine, external on Twitter and on Facebook, external.