Great miscalculations: The French railway error and 10 others

- Published

The discovery by the French state-owned railway company SNCF that 2,000 new trains are too wide for many station platforms is embarrassing, but far from the first time a small mis-measurement or miscalculation has had serious repercussions.

The French fiasco has been blamed by SNCF on the national rail operator RFF. But sometimes there is no-one else to share responsibility. Here are 10 examples where a little error has proved very expensive, or even fatal.

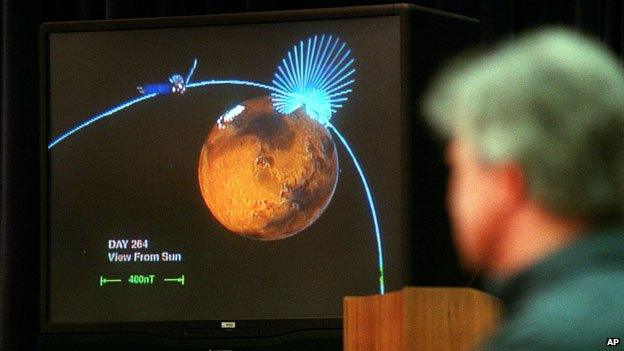

1. The Mars Climate Orbiter

Designed to orbit Mars as the first interplanetary weather satellite, the Mars Orbiter was lost in 1999 because the Nasa team used metric units while a contractor used imperial. The $125m probe came too close to Mars as it tried to manoeuvre into orbit, and is thought to have been destroyed by the planet's atmosphere. An investigation said the "root cause" of the loss was the "failed translation of English units into metric units" in a piece of ground software.

2. The Vasa warship

.jpg)

In 1628, crowds in Sweden watched in horror as a new warship, Vasa, sank less than a mile into her maiden voyage, with the death of 30 people on board. Armed with 64 bronze cannons, it was considered by some to be the most powerful warship in the world. Experts who have studied it since it was raised in 1961 say it is asymmetrical, being thicker on the port side than the starboard side. One reason for this could be that the workmen were using different systems of measurement, external. Archaeologists have found four rulers used by the workmen who built the ship. Two were calibrated in Swedish feet, which had 12 inches, while the other two measured Amsterdam feet, which had 11 inches.

3. The "Gimli Glider"

In 1983, an Air Canada flight ran out of fuel above Gimli, Manitoba. Canada had switched to the metric system in 1970, and the plane is reported to have been Air Canada's first aircraft to use metric measurements. The plane's on-board fuel gauge was not working, so the crew used measuring "dripsticks" to check how much fuel the plane took on during refuelling. Things went wrong when they converted this measurement of volume into one of weight. They got the number right, but the unit wrong - mistaking pounds of fuel for kilograms. As a result the plane was carrying about half as much fuel as they thought. Luckily, the pilot was able to land the plane safely on the Gimli runway, giving the plane the nickname "Gimli Glider".

4. The Hubble Space Telescope

The Hubble telescope is famous for its beautiful space images, and is considered a great success for Nasa. However, it got off to a very rocky start. The first images sent back by the telescope were fuzzy because the telescope's main mirror was too flat. It wasn't out by much - only 2.2 microns, or about 1/50th the thickness of a human hair - but this was enough to put the project in jeopardy. One theory is that a speck of paint on a device used to test the mirror resulted in distorted measurements. Luckily, scientists managed to fix the problem in 1993, using an instrument called the Corrective Optics Space Telescope Axial Replacement (Costar). This cancelled out the error in the main mirror, by matching it in reverse.

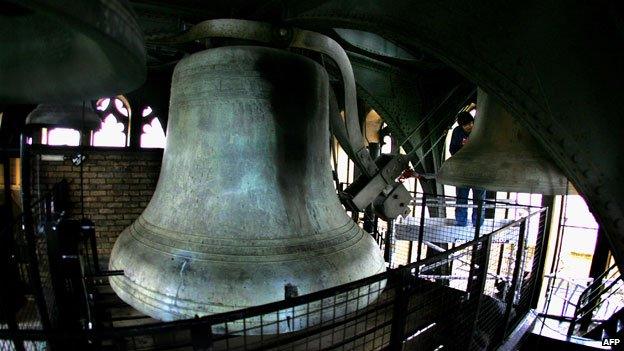

5. Big Ben

The Big Ben bell at the Houses of Parliament in London cracked during testing in 1857 and was melted down to be recast. But the new bell, winched into position over three days in 1859, also quickly cracked. Disputes raged over who was at fault - there was even a libel case. One theory is that the massive hammer, at 6.5 hundredweight, was too heavy - at least for the particular alloy the bell was made from (seven parts tin to 22 of copper). The foundries which cast the bells had always argued this material was too brittle. The second bell was not replaced (it is still cracked), just rotated by an eighth of a turn. The hammer, however, was replaced by a lighter one.

6. Stonehenge model

In the 1984 mockumentary This is Spinal Tap, the members of a fictional rock group order a model of a Stonehenge megalith for their stage show - but the note written on a napkin mistakenly asks for a model 18 inches tall, instead of 18 feet. Curiously, and probably coincidentally, the British rock band Black Sabbath had experienced the opposite problem during its Born Again tour in 1983. Its replica of Stonehenge was so big, it got in the way of the band, and very few of the "stones" would fit on the stage. One version of the story says there was a mix-up between metres and feet.

7. The Laufenburg bridge

What is sea level? It varies from one place to another, and different countries use different benchmarks. "For example, Britain has measured height in relation to mean sea levels in Cornwall, while France measures height in relation to sea levels in Marseille," says Dr Philip Woodworth, of the National Oceanography Centre Liverpool. Germany, for its part, measures height in relation to the North Sea, while Switzerland, like France, opts for the Mediterranean Sea. This caused a problem in Laufenburg, a town that straddles Germany and Switzerland. As two halves of a new bridge grew closer to one another in 2003, it became clear that, instead of being at the same height "above sea level", one side was 54cm higher than the other. Builders knew that there was a 27cm difference between the two versions of sea level - but somehow it was doubled, rather than cancelled out. The German side reportedly had to be lowered before the bridge could be completed.

8. Scott's diet

.jpg)

The polar explorer Robert Falcon Scott made a fatal miscalculation about the amount of food his men would need on their 1910-1912 expedition to the South Pole. They were given rations of 4,500 calories per day, which is now known to be insufficient when hauling sledges, and especially at higher altitudes. According to Dr Mike Stroud, a polar veteran and expert in nutrition, the explorers were getting some 3,000 calories per day less than their bodies needed, and would have lost about 25kg of body weight before they reached their destination and started the return journey. Scott and his companions on the trek to the pole are now assumed to have died of starvation.

9. The Sochi biathlon track

The day before the opening of the Sochi Winter Olympics, it was discovered that the biathlon track - which should be a loop of 2.5km (1.6 miles) - was 40m (130ft) short. Competitors in 7.5km events would have covered less than 7.4km, while those in 12.5km events would have done 12.3km. Some hasty repair work ensured the track was the right length for the first event three days later. Lengthening a biathlon track is clearly easier than lengthening a swimming pool. It's often been reported that 50m swimming pools at Crystal Palace in London and Leeds were made a few centimetres too short - sometimes, it's said, because the designers forgot about the thickness of the tiles. These stories, however, appear to be urban myths. A similar report about Portsmouth's Olympic pool in 2011 also turned out to be incorrect.

10. The Millennium Bridge

To mark the new millennium, London got a new footbridge in June 2000, linking the newly opened Tate Modern art gallery, on the south bank of the Thames, with the north bank near St Paul's cathedral. But people noticed that the 350m-long structure wobbled alarmingly as they walked across. One of the difficulties of designing a footbridge is the "synchronised footfall" effect - as the bridge begins to bounce or sway people adjust their footsteps to the rhythm of the bridge's movements, inadvertently magnifying them. In this case, the designers took account of the up-and-down synchronised footfall, but not the side-to-side effect. The following year, work began to install dampers, like car shock absorbers, to reduce the rocking. It was reopened in February 2002.

Reporting by Helier Cheung and Stephen Mulvey

Follow @BBCNewsMagazine, external on Twitter and on Facebook, external