How a team of students beat the casinos

- Published

When it comes to gambling, everyone knows the casino always comes out on top - right? But in the 1990s a group of students proved the punter didn't have to be the loser. This is the story of the MIT Blackjack Team.

Bill Kaplan laughs, remembering his mother's reaction when he told her he was postponing his entrance to Harvard to make his fortune at gambling. "Oh my God, this is ridiculous! What am I going to tell my friends?" she said.

Kaplan had read a book about card counting and believed he could use a mathematical model to make good money from blackjack. It was certainly not his mother's dream for her straight-A student son.

But Kaplan's stepfather was more open to the idea and threw down a challenge. "Play me every night and prove you can win," he said.

"I crushed him for 2 weeks straight," recalls Kaplan. "He told my mother 'I can't believe this but he can really win at this game - just let him go.' So my mother wasn't wild about it but I went to Vegas and I spent a year there."

That was in 1977 - Kaplan took $1,000 (£600) and within nine months had turned it into about $35,000 (£20,000). He went on to graduate from Harvard and over the years kept playing blackjack around the world.

His life took a dramatic turn when the leader of a small group of students from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) who had dabbled with card counting overheard him discussing his Vegas exploits.

They asked him to train and manage what would later become known as the infamous MIT Blackjack Team.

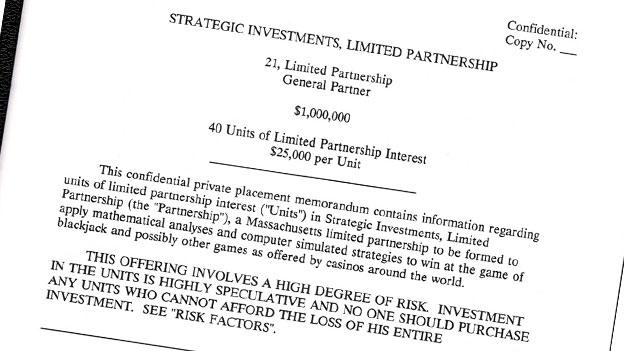

In 1992, with the gambling industry booming and new mega-casinos springing up, Kaplan and his partners saw an opportunity for them to go mega as well.

Friends and partners who had previously seen 100% returns on smaller investments, stumped up a startling $1 million to fund a new company, Strategic Investments, which would train bright students to card count and gamble - and then unleash them on the unsuspecting casinos.

One of these students was Mike Aponte, then a 22-year-old who was unsure what he wanted to do with his life. After perfecting the technique in empty classrooms, he was shocked to be handed $40,000 (£24,000) in cash to gamble on behalf of the team.

He was even more shocked to lose $10,000 (£6,000) of it in his very first ten minutes at a blackjack table in Atlantic City.

"An executive casino host came over right away and greeted me and took me up to a penthouse suite. It had a jacuzzi, pool table - it was amazing. I was in awe of the room but I didn't enjoy it as much as I would normally have, because I was still upset about losing all that money."

It was a lesson in just how volatile blackjack could be - even with a scientifically proven system. But he continued to rely on the team's method that weekend and was, in the end, able to return to college with a net profit of about $25,000 (£15,000).

Casino hosts look after high rollers - clients who gamble big money - and reward them with perks of free food, drinks, tickets and rooms, whether or not they win. So the students, who spent the week going to class, eating in canteens and sharing dorm rooms, soon got used to being treated like VIPs.

But they also had to look the part - something that wasn't easy for many. For Aponte, it was like going undercover. "You just have to pass that initial test where they size you up and think, 'OK, is this someone we're going to make a lot of money from?'"

He says that while skill at maths wasn't a problem for anyone at MIT "what was important was being comfortable, being able to deal with the attention, because money just attracts attention."

As an Asian, Aponte says he had a big advantage. "We really played off that stereotype that Asians are big crazy gamblers. So my standard story was that I came from a rich family and I was the spoiled son."

If the students soon got used to enjoying the perks of casino life, they also grew very relaxed about carrying around a lot of money. Sometimes too relaxed.

One night some members of the team came straight from a gambling trip in Las Vegas to join in a practice session in a MIT classroom. One put a brown paper lunch bag under his chair.

At 06:00 the next morning Kaplan received a phone call. "You won't believe what I've done!" the student said. "You know I came back from Vegas and I had $125,000 (£74,000) in a paper bag? Well I left in the classroom. I totally forgot about it. I ran back and it's not there."

It turned out that a cleaner had put it in his locker. It took six months and investigations by the Drug Enforcement Administration and the FBI before the team eventually got their money back.

Pressure was also growing as more players started being spotted by the casinos and were barred from playing. A private detective had been employed to find them and realised from the Boston addresses of many of those caught that this was a student team from MIT. He even obtained a yearbook including some of their photos.

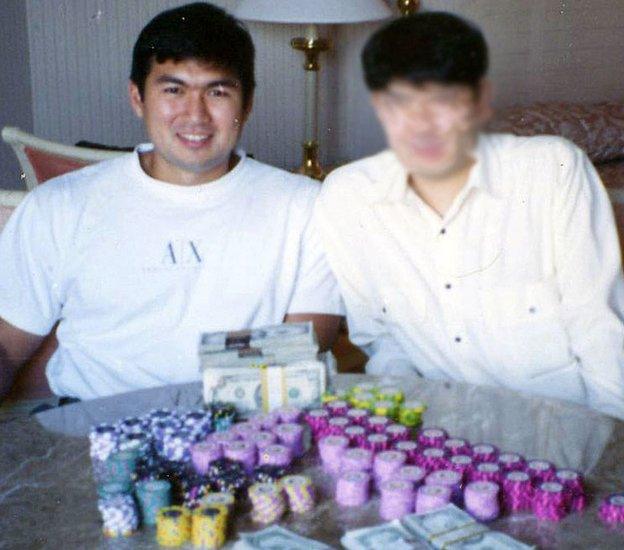

Mike Aponte (left) with one of his biggest wins in later life - some players still remain anonymous

Many worried about being caught, even though Aponte says it was usually quite painless. "You'd get a tap on the back and the security man would say, 'Mike, casino management has decided you're welcome to play any game except blackjack.'"

But he says sometimes security guards could get aggressive and outside of the US it was even more risky.

He remembers the experience of one new team member who had just passed the tests to act as a big player. "Looking back it was a mistake as he didn't have a good look for a big player. He wore glasses, he had a very meek personality, and he just looked really smart. He was really smart - he was a PHD student."

Having just got married, the man thought it would be good to take his new wife, who was also in the team, to the Bahamas and try his luck at the casinos there.

"He was up about $20,000 or $30,000 (£12,000 or £18,000) and the casino figured out he was card counting and they brought the police in.

"They threw them in jail and confiscated not only all the money they'd won but the team money they'd brought with them. That player and his wife - they never played for the team again."

How card counting works

The 2008 film 21 starring Kevin Spacey was inspired by the MIT Blackjack Team's story

In blackjack, or 21, high cards favour the gambler, low cards the casino. So a card counter keeps a running tally in their head, adding 1 for low cards and subtracting 1 for high cards. When their tally increases (meaning more high cards than low ones are left in the deck) they know it's time to start placing higher bets.

Card counters won't win every time - they often lose a lot of money - but statistically, and over time, the odds are in their favour.

It has to be done secretly because although it's not illegal, casinos don't like it and have the right to refuse to let someone play.

It was researched in the 1950s by a mathematics professor from MIT, Edward Thorp, using some of the earliest computers.

In 1962 he published a book about it called Beat the Dealer and forever changed how the gambling public viewed blackjack.

After being caught, many gave up. But some took drastic measures to stay on the team.

Kaplan remembers how one 21-year-old managed to keep playing as a spotter - someone who counts cards and then signals to their partner who places the big bets when the cards were favourable.

"He shaved his head, put on a wig, dressed like a woman and then he played for the longest time. He was a very good looking guy!"

In the end, the increasing pressure meant Strategic Investments was dissolved in December 1993 marking the end of Kaplan's blackjack career.

By then the team had grown to around 80 players and he says it was time to call it quits.

"As a player it's an amazing experience, but as a manager we might have 10, 20, 30 people playing in five different casino locales, some in Las Vegas, some in New Orleans, some in Canada, and we're keeping track of their play, we're trying to make sure no-one's stealing money."

The venture had had mixed success and the money earned wasn't as much as many had hoped, especially as it had to be split between so many players and investors.

Kaplan decided that for the amount he was making, he would be better off investing in property and business.

His wife was relieved people weren't calling at two in the morning saying "I just got kicked out of Caesars what do I do?"

"I was just running a business and it just seemed like so much of the business was more headaches than fun," he says.

After Strategic Investments folded, Aponte went on to form another team, as did other players. Those teams learned from their experiences with Strategic Investments and concentrated more on the personalities of the people they recruited. Mike says the amount of money they won rocketed.

Eventually, Aponte became too well known as a card counter to play but he still makes his living from the game. He became the World Series of Blackjack champion in 2004, he teaches people to play and advises the casinos.

Ironically, he has become friendly with some of the people who used to spend their days hunting for him. But he still looks back at his MIT team days with fondness.

"We pulled off something that very few people have. Everyone knows the golden rule that you can't beat the house over the long run but that's exactly what we were able to pull off."

Bill Kaplan and Mike Aponte spoke to Witness - which airs weekdays on BBC World Service radio.

Follow @BBCNewsMagazine, external on Twitter and on Facebook, external