The elephants’ graveyard: Protecting Kenya’s wildlife

- Published

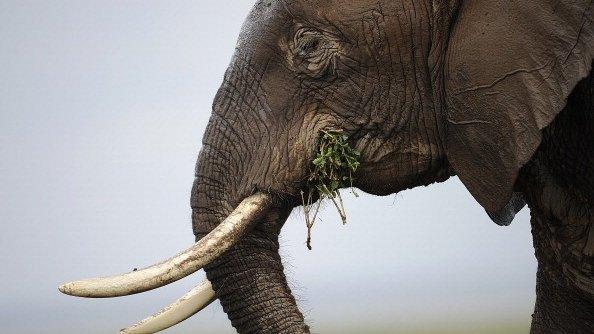

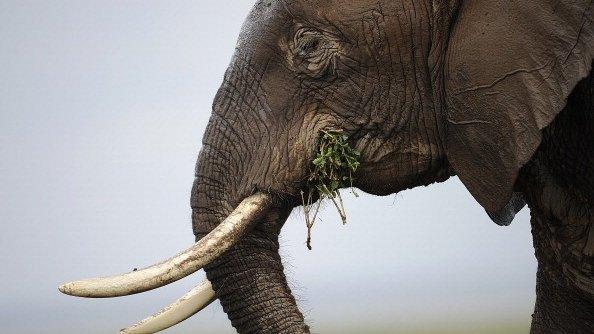

A rise in the demand for ivory has led to poachers illegally killing thousands of elephants every year - and despite the use of GPS tracking systems, rangers are finding it increasingly difficult to protect the animals.

Years ago, while walking with a camel train in northern Kenya, I remember coming across the bleached white dome of an elephant's skull.

Within the smooth hollows of both its eye sockets were bunches of dried grass, fluffy with seed, arranged with evident care. A camel herder told me it was customary, among his people, on passing the skull of an elephant, to pay respect to the fallen giant in this way.

In those days, you rarely saw the skull or bones of an elephant.

There's a legend that elephants have graveyards where they go to die, but science has never proved this.

It's true they will - on finding the skeleton of an elephant - stop and examine it, touch it, sometimes even pick up a bone or a tusk and carry it off.

I once sat and watched with tears in my eyes, as a family of elephants returned to where they'd had to abandon a calf, which had been too weak to stand or follow them.

It had since died, and the tenderness and sorrow that emanated from that desolate little huddle of elephants as they gently explored the lifeless grey body with their sensitive trunks, was one of the most moving scenes I've ever witnessed.

Nowadays, it seems northern Kenya is littered with the carcasses of elephants. Poaching and the relentless ivory trade is laying waste to many of Africa's elephant populations.

Kimeli Maripet is an elephant researcher monitoring their movements across Lewa Wildlife Conservancy, the Ngare Ndare Forest and Mount Kenya, where - for centuries - elephants have followed the same migratory patterns.

A network of conservation organisations working alongside the Kenya Wildlife Service equip foot and vehicle patrols to monitor the vast expanse of northern Kenya.

State of the art GPS telemetry keeps track of certain radio-collared individuals as they follow time-worn routes pioneered by generations of elephants whose own bones have long since turned to dust.

It was Maripet who was detailed to go looking for Mountain Bull.

Mountain Bull was caught on a CCTV camera earlier this year

Mountain Bull wore one of the broad leather collars and satellite transmitters - his daily movements monitored on the researchers' computer screens.

He had earned his name from being one of the most determined elephant bulls in the area, when it came to overcoming obstacles in the way of his chosen path, following his ancestors' footsteps to Mount Kenya. Even electric fences didn't deter these bulls.

They showed great persistence in finding a way up to the forests and moorland, bulldozing the odd farm fence along the way and they crop-raided with impunity as they went. This eventually led to the construction of a purpose-built elephant corridor that crosses beneath a major road with heavy traffic, allowing the elephants to take a safe route, away from farmland, up to their mountain refuge.

But for several days the signal emitted by Mountain Bull's collar hadn't moved. It happens sometimes.

Only a week before, another elephant's signal had remained static for a few days on computer screens, and a search party was mounted.

That collar was found - torn and lying on the ground, still sending its signal up to space and the elephant was soon spotted nearby, unharmed.

That's what you always hope is the case, says Maripet. Collars do sometimes break and drop off, necessitating the elephant being tranquilised again to have a new one fitted.

So, armed with a satellite receiver and coordinates of Mountain Bull's GPS signal, Maripet and a scout from the Mount Kenya Trust set off to look for him.

After two days, they came across the tracks of an elephant which appeared to have stood still for a long while, before heading - falteringly - into a thicket of bamboo.

Mountain Bull was lying on his side with a deep spear wound in his back.

Triggered by his weight on some sort of trip wire, a spear, strategically positioned in an overhead branch, must have dropped and lodged in the elephant's spine. He was dead. And his tusks had been hacked from his face.

It was heartbreaking hearing Maripet's account of how the elephant had met his fate.

No doubt the poachers had waited nearby, and - once the bull toppled onto his side - wasted no time in drawing out their machetes and hacking out his beautiful creamy tusks.

Had the elephant even drawn his last breath, I wondered?

I recall the grasses in the skull of that elephant, years ago, and ask Maripet if he knew of the custom.

"Oh yes," he says. "It's our way of saying, sleep tight, comrade."

How to listen to From Our Own Correspondent, external:

BBC Radio 4: Saturdays at 11:30 and some Thursdays at 11:00

Listen online or download the podcast.

BBC World Service: Short editions Monday-Friday - see World Service programme schedule.

Follow @BBCNewsMagazine, external on Twitter and on Facebook, external

- Published11 April 2014

- Published12 February 2014

- Published19 September 2013