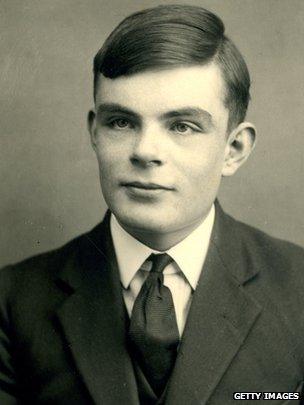

What was Alan Turing really like?

- Published

Alan Turing is commemorated by a statue in Bletchley Park

It's 60 years since Alan Turing killed himself. In his lifetime he was almost unknown to the public yet today he's famous both as a pioneer of computing and as someone lacerated by 1950s attitudes to sexuality. But sisters Barbara Maher and Maria Summerscale can recall him as a family friend.

When Alan Turing died of cyanide poisoning in June 1954 his death was not huge news. The story of how he and colleagues at Bletchley Park had cracked the German Enigma codes was still secret and the Turing name was not yet public property.

In a two-paragraph story reporting his death, the Times described how he had "helped to develop a mechanical brain which he said had solved in a few weeks a problem in higher mathematics that had been a puzzle since the 18th Century". It also noted his work on the Ace "automatic computing machine". A short obituary followed a few days later.

Turing had contributed to a couple of radio programmes on the BBC Third Programme (sadly now lost) but otherwise his wide-ranging work on artificial intelligence and morphology seemed the stuff of specialist journals.

His name emerged from the shadows in 1983 when Andrew Hodges published a well-received biography which inspired the play Breaking the Code. It played in London and on Broadway and was later adapted for TV. The public image of Turing as tortured gay genius was taking shape.

Yet long before the icon, the Greenbaums knew the man. The memories of Barbara and Maria Greenbaum (now Barbara Maher and Maria Summerscale) remain vivid.

Turing came into their lives as a patient of their father Franz Greenbaum in the autumn of 1952. "Our father had trained as a Jungian psychologist," says Barbara. "He was Jewish and got out of Berlin just in time. In 1939 he settled in Manchester where he had a private practice in Palatine Road in Didsbury."

Maria Summerscale (left) and Barbara Maher knew Alan Turing when they were growing up

Her younger sister Maria, born in 1945, was seven when she first met Turing. "It wasn't unheard of for patients to come to the house in Longton Avenue but nor was it common. I was only a little girl but I think I knew that because he was a regular visitor he must be a friend of my father's."

Barbara says a friend of Turing had suggested he should see Dr Greenbaum - someone who would be able to empathise with his problems.

In March 1952 Turing, working at Manchester University, was prosecuted for gross indecency. The police had worked out he was in a relationship with Arnold Murray, twenty years his junior, and Turing fell foul of the draconian anti-gay laws of the period.

To avoid prison he agreed to take a course of the hormone oestrogen which was intended to suppress his libido. In the meantime Arnold Murray drifted out of his life. (He died in 1989.)

Barbara says she knew Turing was homosexual but thought little of it. "Our father was very broad-minded and a liberal person. He thought he could help Alan Turing come to terms with the person he was."

Maria believes that being younger her view was simple. "I just saw Alan as a very warm and friendly person who always took an interest in what I was doing. He would come for dinner and often I'd be sitting on the floor playing the board-game solitaire. He would sit down on the carpet next to me and we would talk. I became quite attached to him."

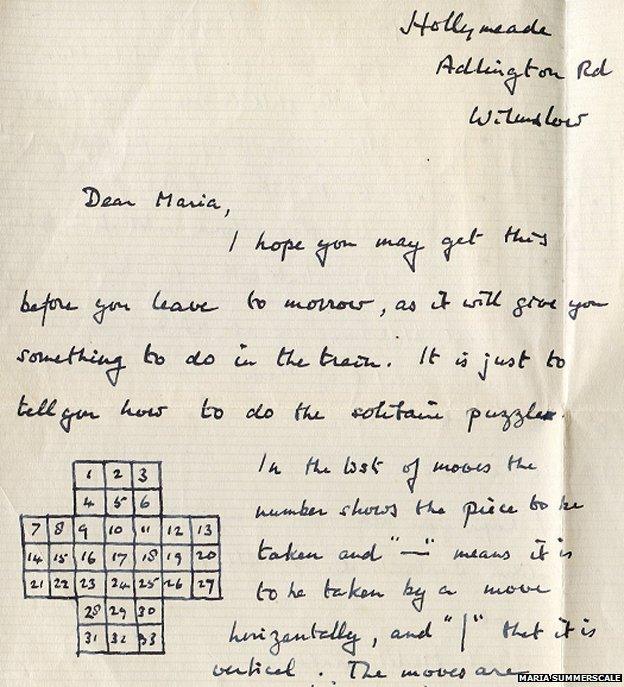

Maria still treasures a letter Alan sent in the summer of 1953, less than a year before his death. He sets out how to tackle the game. "To this day I can't really fathom out what he's telling me. But to an eight-year-old, getting a letter like that from a grown-up was special."

A complete lesson in logic from an acknowledged mathematical genius, written in his own hand, is an extraordinary thing to possess. It's reproduced here, in part, for the first time.

Barbara says to her slightly older eyes Turing was an interesting man. "But he was very gauche. He was embarrassed with himself. He dressed in a very unkempt manner. And he stammered quite heavily, which has been rather missed. He bit his nails too so I think he had issues.

"But he obviously enjoyed coming into the family home and really being part of the family. And I suspect our father liked his scientific brain - there was an empathy between them because of that."

Turing even went with the Greenbaum family on a day trip to the seaside resort of St Annes. But Barbara recalls it ended badly.

"Alan turned up at our house in a very strange outfit, which looked like his school cricket whites. White trousers which came half-way up his ankles and a white shirt which was very creased and crumpled. But it was a lovely sunny day and Alan was in a cheerful mood and off we went.

"Then he thought it would be a good idea to go to the Pleasure Beach at Blackpool. We found a fortune-teller's tent and Alan said he'd like to go in so we waited around for him to come back.

"And this sunny, cheerful visage had shrunk into a pale, shaking, horror-stricken face. Something had happened. We don't know what the fortune-teller said but he obviously was deeply unhappy. I think that was probably the last time we saw him before we heard of his suicide."

Maria remembers hearing about the tragedy. "I was very upset when my mother told me that he had died. That was for me the first experience of the death of someone who was quite close."

The inquest decided that Turing had killed himself using cyanide. A partially eaten apple was by his side in bed but as it was never tested it's impossible to say if it was laced with poison as has been suggested.

Extract from Turing's letter explaining the principles of Solitaire

An alternative interpretation is that he inhaled or ingested cyanide by accident during a chemistry experiment. But Turing's first biographer Andrew Hodges believes the verdict was accurate.

In the 31 years since the publication of his book Alan Turing's status has changed radically. "At the time almost every publisher turned me down. They said nobody would be interested," says Hodges. "Of course I'm proud the book introduced him to so many readers."

But two developments since would have pushed Turing into the public consciousness anyway.

"One is that computers now dominate our lives in a way even Alan could never have foreseen," says Hodges. "So there's been a boom in people wanting to understand how they developed. You can't tell that tale without Alan Turing."

The other shift has been in attitudes towards homosexuality.

"I started my research in 1977 only a decade after homosexual acts became legal in England and Wales," says Hodges. "Some people were still ill-at-ease at that point contemplating Alan's sexuality. Sixty years ago Alan Turing was subjected to chemical castration for the crime of being gay. It's shocking now.

"How he would have loved to see the changes in terms of same-sex equality. He received a royal pardon last year but how terrible he didn't live to see a more civilised nation emerge."

Listen to Witness: The Death of Alan Turing on BBC iPlayer

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.