World Cup: The joyful dearth of World Cup hype

- Published

Pessimism about England's chances has made this the most hype-free World Cup the country has seen for years. For supporters of the non-English parts of the UK, and the football-averse, it makes a welcome change, says one Scotland supporter.

The flags are missing from the cars. British newspapers aren't heralding imminent victory. In pubs from Penrith to Plymouth there's a distinct lack of gaiety, optimism and hope.

I for one couldn't be happier.

As a Scotsman resident in London, I've come to dread the wildly delusional over-confidence that grips my adopted homeland every time an international football tournament is staged.

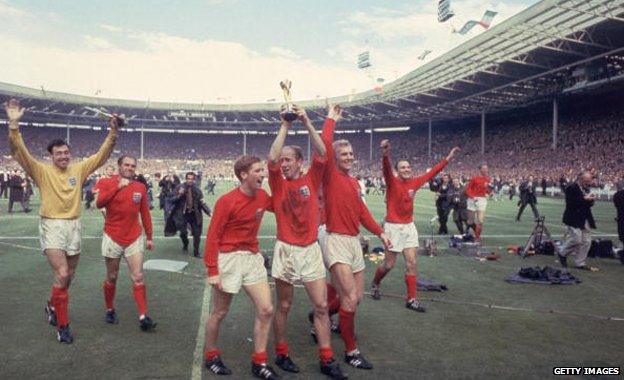

The certainty of victory. The talk of a "golden generation". The interminable references to 1966. And the inevitable splutterings of anguish when it's eventually confirmed on the pitch that, actually, Germany or Argentina or Portugal are superior teams after all.

Now, don't get me wrong. I like all things Anglo very much. While Scotland will always be the national side I support, in spite of our dependable rubbishness, I've always felt the Anyone-But-England tendency among some of my fellow Scots diminishes our status as a self-confident, modern nation.

1966 - it seems like only yesterday to many England fans

But the bellicose hysteria that envelops many in England - not to mention the irritating assumption by certain broadcasters, newspapers and advertisers that their audiences are comprised entirely of England fans - makes the team in white a difficult one for non-English folk to like, never mind cheer on.

And I say all this as someone who takes an interest in football. For those who dislike the game, it must be excruciating.

This year it's different, however. No-one with more than a cursory knowledge of the international game seriously believes England will win.

Manager Roy Hodgson does everything he can to dampen expectations, short of holding up a pink betting slip inscribed with "£50 Brazil 3/1". Pundits are self-consciously measured in their predictions.

Everywhere you go, the cross of St George is far less visible than at any World Cup since 1994, the last occasion England failed to qualify.

At this stage in 2010, Ladbrokes had taken nearly £500,000 on England winning as 6/1 shots. So far this year they have received less than £80,000 at 28/1, according to spokesman Alex Donohue.

"In recent years England's football team have paid for every birthday and Christmas for the bookmakers, but it's not the same anymore," he says.

During a warm-up game at Wembley against Peru, home fans "were far more excited about throwing paper darts on the pitch than cheering the boys off across the Atlantic", says Mark Perryman, author of Ingerland: Travels With a Football Nation. "I can't ever remember such an uninterested crowd."

As a neutral I'm looking forward to watching the World Cup without the hysteria that usually surrounds modern competitions.

Given that Scotland have failed to qualify for any tournament since 1998, English fans might well accuse Celtic naysayers like me of jealousy - and in my case the charge is entirely accurate. But I don't think pointing out the ludicrousness of the manner in which the England side has been habitually puffed up is entirely borne of spite.

What irritates fans of the UK's other nations is that the songs about "30 years of hurt" (now 48 and counting, in case you needed reminding) betray a barely-concealed sense of entitlement - the notion that, since England gave the game to the world, it deserves automatically to be considered a top footballing nation, regardless of the actual quality of its current players.

In fact, as Simon Kuper and Stefan Szymanski argued in their book Why England Lose, the English national side more or less punches its weight, when population size, GDP and experience in international football are all taken into account.

Better make that 48 years of hurt: Wayne Rooney contemplates England's World Cup exit in 2010

It's true that in some years - notably 1990 - England's chances of lifting the trophy have been rather better than fanciful. And at Euro '96, as the host nation, Terry Venables' side were arguably unlucky not to progress beyond the semi-finals.

But enlightened English fans acknowledge the hype that has spiralled around their national team has been self-defeating.

Perryman observes that ahead of Italia 90, England's most successful recent World Cup, it was widely considered improbable that England would qualify from their group. By contrast, the 2010 4-1 humiliation at the hands of Germany in Bloemfontein came as the hysteria reached its apex.

"You don't have to be Steve Peters" - the sports psychiatrist Hodgson is bringing to Brazil - "to see that these expectations put an incredible psychological load on the players' shoulders", adds Perryman.

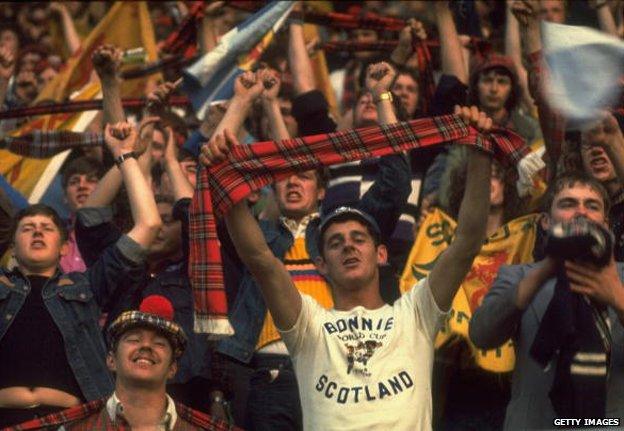

Not that England is the only nation capable of allowing expectations to run out of control. Surely the most dementedly hubristic World Cup campaign in living memory was Scotland's jaunt to Argentina in 1978. Manager Ally MacLeod declared beforehand: "I think a medal of some sort will come" - meaning his side would finish in the top three - "and I pray and hope that it is the gold one".

There was also a prematurely triumphalist send-off at Hampden Park. Inevitably, the squad failed to make it beyond the first round (Archie Gemmill did, of course, score one of the greatest World Cup goals of all time, external along the way).

The Argentine debacle forced Scottish football to undergo a reality check and it's possible Bloemfontein has had a similar effect on England.

"We are pretty au fait with it now, but the English are slowly starting to realise where they stand in the grand scheme of things," says Susan Morrison, co-author of Rose Versus Thistle, a history of the Anglo-Scottish sporting rivalry.

Scotland's Argentina debacle, 1978

Perhaps over time this will lessen the antipathy of fans of other home nations towards the England side. It's hard to really hate someone that, fundamentally, you feel sorry for.

While the current England set-up lacks the obvious stars of previous campaigns, its personnel are far easier for the neutral to warm to. There's Rickie Lambert, with a Roy of the Rovers backstory that took him from a beetroot factory via Macclesfield Town to Brazil. There are young talents like Raheem Sterling, Daniel Sturridge and Luke Shaw. There's Hodgson himself, with his Steptoe and Son accent and fondness for Milan Kundera.

Plenty of England fans agree. "It was hard to get behind John Terry and Ashley Cole and players like that, but this time there's no-one I actively dislike," says writer, publisher and Scunthorpe supporter Scott Pack.

And what about me? While I've never cheered against England during my 12-and-a-half years south of the Border, I've never actively cheered for them, either.

We'll see how this tournament goes. There's plenty of time for commentators to annoy me by, say, comparing Phil Jagielka to Bobby Moore.

But it's not entirely impossible that the next St George's cross you see fluttering from a window will be mine.

Illustration by Gerry Fletcher

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.