How Uruguay broke Brazilian hearts in the 1950 World Cup

- Published

Sixty-four years ago Brazil hosted the World Cup and its team were hot favourites to win, but the final match was to produce one of the greatest upsets in the tournament's history.

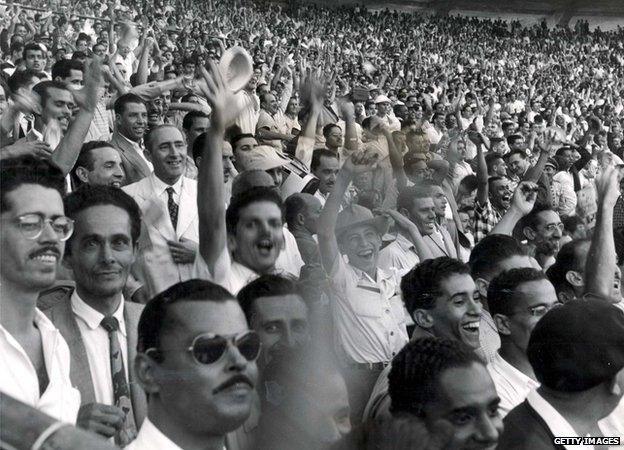

On 16 July 1950, the Uruguayan winger, Alcides Ghiggia, walked out in front of about 200,000 Brazilian fans at the Maracana Stadium in Rio de Janeiro.

"It was a fantastic atmosphere. Their supporters were jumping with joy as if they'd already won the World Cup," he says.

Brazil was so confident of winning the tournament that a samba band stood on the sidelines of the pitch, ready to play a new song called Brazil the Winners. Local newspapers had already printed special editions proclaiming the hosts "Champions of the World".

"Everyone was saying they'd thrash us three or four nil. I tried not to look at the crowd and just to get on with the match," Ghiggia recalls.

For Brazil, winning the 1950 World Cup was a national priority. The government hoped that football would unite the country and mark it out as an emerging international power.

As the centrepiece, Brazil had built the Maracana, a huge new concrete stadium designed to be the biggest in the world.

About a tenth of the population of Rio de Janeiro crammed inside for the final game of the tournament - among them Joao Luiz de Albuquerque, then an 11-year-old schoolboy.

Brazil had scored 13 goals in their previous two matches, so like every other Brazilian, Albuquerque believed despatching tiny Uruguay would be a mere formality.

"Nobody was the slightest bit nervous. Everybody told me we'd win - my family, my friends, even the milkman," he says.

After a shower of confetti had been cleared from the pitch, the Brazilians imposed themselves, creating numerous chances in the first 45 minutes. Two minutes into the second half, they went 1-0 up and Albuquerque and his parents started to celebrate, believing the inevitable walkover had begun.

"Two hundred thousand people in the Maracana were all saying, 'Yes, there it is... What did I tell you?'" he says.

But, paradoxically, that Brazilian goal would turn the match in favour of the underdogs.

"Our captain said, 'Look lads, we've got to go for it,' and so we started to attack, attack, attack," Ghiggia says.

Gradually, Ghiggia got the better of his Brazilian marker and, on 66 minutes, he put in the cross which led to Juan Alberto Schiaffino scoring the equaliser for Uruguay.

Then, with 11 minutes left, the winger got the ball again and bore down on the Brazil goalkeeper, Moacir Barbosa.

Unsure what Ghiggia would do this time, Barbosa hesitated, leaving a tiny gap between himself and the near post.

"I had a split second to decide what to do. I shot, and it went in off the post... It was the best goal I ever scored," Ghiggia says.

But, as he peeled away to celebrate, Ghiggia noticed that the huge stadium had fallen silent.

"Three people have silenced the Maracana - Frank Sinatra, the Pope and me," he says.

Albuquerque was among the shocked Brazilians. "It was like going to the house of a friend whose father or mother had died. That was the moment to cheer our team on, but instead we just went quiet," he remembers.

The funereal atmosphere seemed to sap the will of the Brazilians, who failed to put Uruguay under pressure in the last few minutes of the game.

At the final whistle, many Brazilian fans wept inconsolably, while Albuquerque was completely stunned. "I remember we didn't move for 10 or 15 minutes. I don't remember the World Cup coming out or anything. I just thought the worst thing in the world had happened to me," he says.

On the pitch, there were also tears. While the Brazilian players cried with grief, the Uruguayans wept with a mixture of joy and disbelief as they did a lap of honour of the stadium.

"We went crazy with happiness. I remember feeling a bit sorry for the Brazilians when we looked at the stands, but ultimately I'm a Uruguayan and winning the World Cup was the highlight of my career," Ghiggia says.

After the defeat, many bars and restaurants in Rio de Janeiro closed for the rest of the day because nobody in the city, renowned for its carnival atmosphere, was in the mood to go out. The newspapers quickly changed their headlines to report on what O Mundo Sportivo called in a headline "Drama, Tragedy and Farce".

The match became known as the Maracanazo, which roughly translates as the great Maracana blow, and would haunt Brazilians for decades to come. Brazilian football legend Pele, who listened at home on the radio, always remembers that it was the first time he saw his father cry.

"Football was supposed to be this great expression of Brazilianness," says Alex Bellos, author of Futebol: the Brazilian Way of Life. "The defeat reinforced the sense that actually Brazilians were just doomed to be failures on the edge of the world."

Brazil have gone on to win the World Cup five times, but Ghiggia says that whenever he visits their country, Brazilians remind him that they still feel the pain of the Maracanazo.

"It was a heavy blow for them. The Brazilians had just assumed they'd be world champions, and it went completely wrong," he says.

Ghiggia was invited to the draw for this year's World Cup finals - the first time Brazil has hosted the tournament since 1950. He says he was given a friendly reception, but that Brazilian officials told him the one thing they do not want in 2014 is another final in the Maracana against Uruguay.

Listen to Alcides Ghiggia on Sporting Witness on BBC World Service Service at 1350 GMT on Saturday 14 June and later on BBC iPlayer

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.