No ordinary newspaper

- Published

The News of the World wasn't an ordinary newspaper when Andy Coulson was its editor. It had another team you didn't find in your average tabloid newsroom.

Alongside the news reporters and feature writers, there was a department of criminality - a conspiracy at the heart of his newspaper to get the story at any cost.

The conspiracy reached the parts of people's private lives that the competition couldn't even know about.

The ultimate aim was to ensure that the News of the World remained Britain's biggest-selling Sunday newspaper, bringing in the profits for its parent company, News International.

An Old Bailey jury has now found Coulson, the newspaper's editor between 2003 and 2007, guilty of conspiracy to hack phones. His predecessor and News International's former chief executive, Rebekah Brooks, has been cleared of the same charge - as has the former managing editor Stuart Kuttner.

The jury's verdict at the hacking trial means the conspiracy operated at every level of the News of the World's hierarchy. It involved reporters, the news desk and an editor who rose from local journalist to be Prime Minister David Cameron's communications director.

And that conspiracy brought down a British journalistic institution that was read and loved by more than three million every Sunday. The last edition rolled off the presses on Sunday 10 July 2011. The full-page editorial declared: "Quite simply, we lost our way."

Hacking: Who pleaded guilty? (clockwise from top left):

•Greg Miskiw, former news editor

•Neville Thurlbeck, former news editor and chief reporter

•James Weatherup, former news editor

•Dan Evans, reporter

•Glenn Mulcaire, private investigator - prosecuted on two occasions

•Clive Goodman, in 2006. Prosecuted this time for corrupt payments

This was not the first hacking trial - and it may not be the last.

Taken alongside other guilty pleas before the trial, the verdict puts paid to the idea that former royal editor Clive Goodman and private investigator Glenn Mulcaire, convicted in 2006, were the only people ever involved.

The newspaper insisted that Goodman was one rogue reporter. But subsequent investigations by the Guardian and New York Times newspapers revealed that News International had secretly settled other cases. Strangely, Scotland Yard had seized evidence that showed voicemail interception was widespread - but it had not acted upon it. Officers had not told other potential victims, despite evidence that there could be hundreds of them.

Glenn Mulcaire teaching someone how to listen into voicemails

The revelations led to more hacking victims coming forward - and more damages claims and pay outs.

Ultimately in 2011, the police launched the mammoth Operations Weeting and Elveden and arrests followed. This trial was about what Weeting and Elveden brought to court.

Phone hacking began in the 1990s because a security flaw meant that anybody could access another mobile phone user's voicemail - providing they had a little bit of technical know-how.

Andy Coulson

Mulcaire, a lower-league professional footballer, had a sideline as an investigator selling information to newspapers. He had a network of contacts and an array of techniques to acquire personal information. Hacking was one of the tools in his box. He has admitted being part of the conspiracy to hack phones for the News of the World.

At the heart of the case against him and others were: News International paperwork and emails, almost 700 tapes Mulcaire kept of his voicemail and other recordings, and a vast archive of 8,000 notes detailing the people he had targeted.

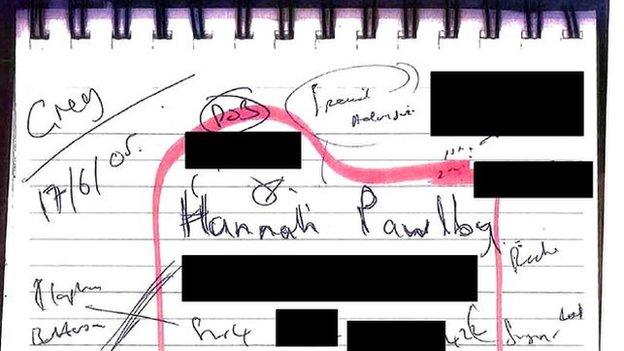

On the top left hand corner of each note, Mulcaire would scribble the name of the journalist who had "tasked" him to acquire personal information.

One of Glenn Mulcaire's note relating to targeting a former ministerial adviser

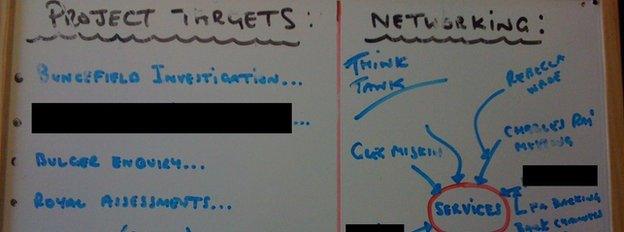

A whiteboard seized from Mulcaire when he was arrested

His notes contained the names of at least 28 News International employees. One whiteboard included the name Rebekah Wade, as she was then known. She told the trial that she had never heard of Mulcaire before the scandal came to light.

Mulcaire's first "tasking" that we know of was on 3 June 1999 and it related to the actor Christopher Guest, also known as Lord Haden-Guest, husband to actress Jamie Lee Curtis. In the corner of the note, Mulcaire had scribbled "Greg".

At the time, Mulcaire worked for the newspaper on a freelance basis under the direction of Greg Miskiw, the then news editor. Miskiw has also pleaded guilty to conspiracy to hack phones.

In late 2000, the News of the World formalised its relationship with Mulcaire by signing the first of a series of contracts for his exclusive services.

According to evidence at the trial, Mulcaire received more than 540 "taskings" from co-conspirators while Rebekah Brooks was editor. Detectives were able to establish 12 incidents of confirmed hacking during her time - although she told the jury she had no knowledge of what had been going on. It was the revelation of one of those that brought the newspaper down.

Milly Dowler went missing from her home in Walton on Thames in 2002. She was abducted and murdered by Levi Bellfield, now serving life for his crimes.

But in April 2002, as the police hunt for her continued, Glenn Mulcaire was tasked to hack her phone, looking for an angle nobody else had.

Mulcaire listened to her messages and he found one that sounded like the teenager was trying to get a job 150 miles away. The message from a Telford recruitment agency had been left completely by accident. It was meant for another woman - the name didn't even sound the same.

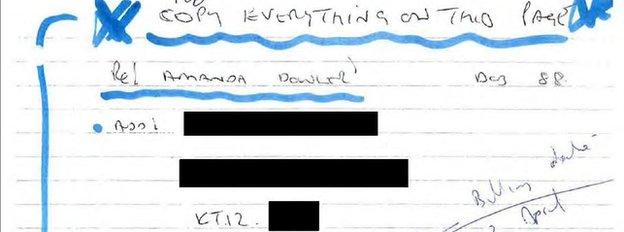

Neville Thurlbeck, who has pleaded guilty to conspiracy to hack, and managing editor Stuart Kuttner shared the information with Surrey Police. Kuttner sent an email to the force explaining that the newspaper had "messages left on Amanda Dowler's mobile phone".

The email that Kuttner sent to the force was the key allegation he faced - but he told the jury he had passed on "all the information that I had been given" - and denied authorising reporters to hack phones.

The Guardian newspaper's revelation in 2011 that the newspaper had hacked a murdered girl's phone turned the News of the World into a toxic brand.

Part of Glenn Mulcaire's notes on hacking Milly Dowler's phone

But Milly Dowler was not the only murder victim who was hacked.

Clare Bernal was a beauty consultant at the Harvey Nichols department store in London who was killed by a stalker in September 2005.

Patricia Bernal, Clare's mother, said the family fell under a media siege. She told the BBC that she received cash through the letterbox from the News of the World as an offer to tell her story. Her partner pushed it back out again.

Years later, Mrs Bernal received a visit from detectives assigned to Operation Weeting, the re-opened investigation into the hacking affair. They had been trawling through Glenn Mulcaire's notes and had found her daughter's name.

"I felt that Clare had been violated," says Mrs Bernal. "It just made me feel physically sick. My daughter was dead but they [the News of the World] would have had access to voice messages. They would have found an awful lot out about my daughter who was a very shy and private person.

"It was like her diary was exposed to the world."

Mrs Bernal has since received an admission from News International that her dead daughter was targeted - but that apology came years after hacking had been integrated into the engines of the newsroom.

Mulcaire's own notes show that during Coulson's editorship, he received at least 1,350 taskings. The news desk would commission Mulcaire to work on a story - or sometimes just a rumour - and his information would be used to assist in landing the exclusive.

Sometimes Mulcaire would tell other News of the World staff how to listen to voicemails themselves.

Clive Goodman, the newspaper's royal editor, made hundreds of his own interceptions. He hacked princes William and Harry - and Kate Middleton 155 times. It was the interception of one royal household message in 2006 that ultimately led to him being caught.

He told the trial that hacking became so important that it was occurring on "an industrial scale". One news editor even began to hack Coulson so that he could hear messages left for the editor by his rivals in other parts of the newspaper. There was evidence at the trial that even Rebekah Brooks was hacked.

Dan Evans, a former Sunday Mirror and News of the World journalist, has also admitted being part of the conspiracy. He told the jury that Coulson recruited him partly because of his interception skills - and that the paper's senior team put him under huge pressure to get results.

Editors in arms: Rebekah Brooks and Andy Coulson at a party in 2004

The jury heard that the newspaper gave him "burner phones" - mobiles that he would regularly throw away. He would sit at his desk and "drop my head and hack there and then".

When in 2005 he targeted actor Daniel Craig and found a message suggesting he was having an affair with fellow actor Sienna Miller, the reporter said that his editor was delighted.

One of Coulson's team allegedly joked that Evans was now "a company man". Coulson vehemently denied Evans's claims.

Politicians were the third group to be targeted, alongside crime victims and celebrities.

For instance, Mulcaire spent a vast amount of time and energy chasing a false rumour that Home Secretary Charles Clarke was having an affair with his adviser Hannah Pawlby in 2005.

The investigator's note revealed that he not only targeted her, but gathered confidential information on her parents, grandparents, family friends - including a senior MI6 officer - and neighbours.

The previous year he had done the same to Mr Clarke's predecessor, David Blunkett. Mulcaire went for Kimberly Quinn, also known as Fortier, who was in a relationship with the cabinet minister.

A draft version of that story, prepared by Neville Thurlbeck - and 300 voicemail recordings harvested from the target's phone - were found in the safe of a News International lawyer.

Bethany Usher was a News of the World reporter during Coulson's time. She grew up in a working-class area of Sunderland and says she believed the newspaper spoke to, and for, people from her community.

Now a journalism lecturer for Teesside University, she says the reality of the newspaper was completely different - it was obsessed by celebrities and scandals, rather than stories that mattered to real people.

In hindsight, she wonders why news editors would demand she hand over contact numbers for interviewees - including families of soldiers killed in action.

"They gave me an interview because they believed I would do justice to their loved one," she says. "The idea [others at the newspaper] would have hacked their phone disgusts me. I don't know whether they did, I hope not."

Whether any of Ms Usher's former colleagues can answer that question didn't matter to this jury.

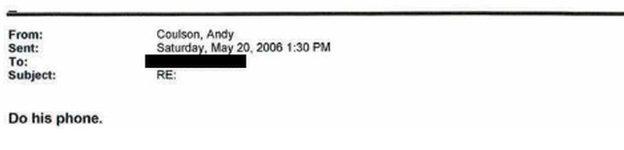

Despite being a prosecution of exceptional complexity, hampered by huge chronological gaps because critical internal emails are missing, the trial came down to three words which appeared in an email from Andy Coulson to one of his news editors: Do His Phone.

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.