Why Icelanders are wary of elves living beneath the rocks

- Published

Plans to build a new road in Iceland ran into trouble recently when campaigners warned that it would disturb elves living in its path. Construction work had to be stopped while a solution was found.

From his desk at the Icelandic highways department in Reykjavik, Petur Matthiasson smiles at me warmly from behind his glasses, but firmly.

"Let's get this straight before we start - I do not believe in elves," he says.

I raise my eyebrows slightly and incline my head towards his computer screen which is displaying the plans for a new road in a neighbouring town. There are two yellow circles marked on the plans, one that reads Elf Church and another that reads Elf Chapel. Petur sighs.

"Ok," he acknowledges wearily. "But it's not every day in Iceland that we divert roads for elves. It's just in this case we were warned that elves were living in some of the rocks in the path of the road - well, we have to respect that belief." He grins shyly and picks up his car keys.

"Come on, I'll show you where the elves live," he says indulgently.

The elf chapel and the highway

Work on the highway to link the Alftanes peninsula to the Reykjavik suburb of Gardabaer was halted when campaigners warned it would disturb elf habitat and a protected area of untouched lava

The chapel (pictured, with Petur) is a 12-foot-high jagged rock

The matter was resolved in part when a local lady who claims to talk to elves, mediated and they agreed to the road so long as their chapel was carefully moved and put elsewhere

The highways authority will not reveal the cost of moving the rock, but says it weighs 70 tonnes and they will have to hire a crane

Surveys suggest that more than half of Icelanders believe in, or at least entertain the possibility of the existence of, the Huldufolk - the hidden people.

Just to be clear, Icelandic elves are not the small, green, pointy-eared variety that help Santa pack the toys at Christmas - they're the same size as you and I, they're just invisible to most of us.

Mainly they're a peaceable breed but if you treat them with disrespect, for example by blasting dynamite through their rock houses and churches, they're not reticent about showing their displeasure.

During our car journey, Petur tells me several stories about how elves are suspected to be behind bulldozer breakdowns and a series of workmen's accidents.

As I step out of the car at the site of the elf church a vicious gust of icy wind punches me full in the face making me stagger backwards on to the black, volcanic rock.

Iceland's rugged landscape is no bucolic idyll - the very ground boils and spits irrationally, the surrounding craggy, black mountains fester menacingly and above, the sky is constantly herniated by the iron-grey clouds it strains to hold up.

It's a visceral, raw and brutal beauty which makes Heathcliff's Wuthering Heights look like a prissy, pastoral watercolour.

"You can't live in this landscape and not believe in a force greater than you," explains Professor of Folklore Adalheidur Gudmundsdottir when I visit her at the university.

She looks at me imploringly. "Please don't portray Icelanders as uneducated peasants who believe in fairies, but look around you and you'll understand why the power of folklore here is so strong," she says. It is of course also strong in the tourism trade.

On the main road into town from the airport, "Elves Live Here" signs try to lure the fanciful into spending a few thousand krona (a few pounds) on a tour of an elf village, a CD of mystical music, or for the less whimsical, perhaps an "I had Sex with an Elf in Iceland" T-shirt.

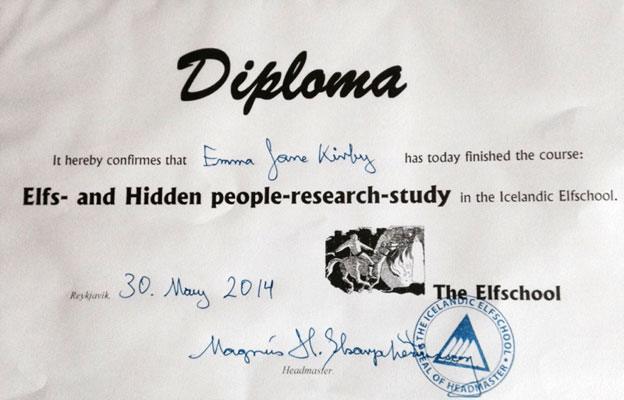

There's even an elf school in the capital at which I dutifully enrolled.

Magnus Skarphedinsson, the headmaster, a rotund, ebullient chap who ate large quantities of breakfast cereal during my one-on-one lesson, had regrettably never seen an elf himself although he did own an old cooking pot that apparently had once made stews in an elf kitchen before the bottom rusted away.

His eyes twinkled so wickedly throughout the class that at the end I asked if he wasn't some kind of malevolent fairy himself.

Petur and I have now reached the 12-foot-high jagged rock that's apparently home to the elf chapel. I scour it closely but apart from an insect or two scuttling to find some shelter in its moss-encrusted crevices, I can see no signs of any life, mythological or other. Petur eyes me suspiciously.

"I could tell you about our family elf," he begins tentatively. I encourage him to tell his tale and learn that Petur's family had a protective elf in the wild north of the country who'd brought them good fortune.

When he'd gone on a camping trip to the isolated area, his father asked him to go and pay his respects to the elf and to thank her.

"But I don't believe in elves so I sort of forgot," he says. The next day, despite the overcast sky and drizzle, he woke up so badly blistered by what appeared to be sunburn that he could barely stand.

As we turn into the blustering wind we catch each other's eye. We both have one hand gripped on to the rock with the desperation of gamblers clinging to a lucky charm. We walk back towards the car in a smug complicity of being almost non-believers.

How to listen to From Our Own Correspondent, external:

BBC Radio 4: Saturdays at 11:30 and some Thursdays at 11:00

Listen online or download the podcast.

BBC World Service: Short editions Monday-Friday - see World Service programme schedule.

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.