A craze for 'loom bands'

- Published

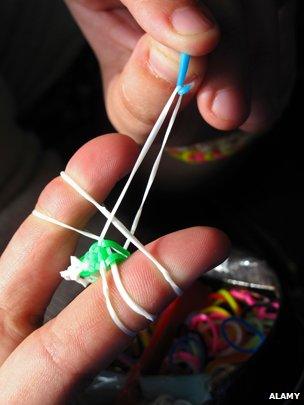

Eight-year-old Mimi explains why she loves loom bands and demonstrates the basics

Why are "loom bands" one of the most popular toys in the world at the moment?

In this era of babies playing with tablets and young teenagers living and breathing social media, it seems curious to find that rubber bands are a big thing.

Playgrounds and living rooms are under invasion from coloured bands. Children are spending hours twisting them into bracelets. Parents are getting tired of picking them up from behind sofas and off the floor. Some schools have even banned them after pupils used them as weapons.

The Rainbow Loom, a plastic device for turning small rubber bands into jewellery, has sold more than three million units worldwide. The sheer scale of the craze can be seen in the stats for Amazon UK. All 30 of the best-selling toys are either looms or loom-related. The products top the sales list for every age group except the under-twos.

The Duchess of Cambridge wore a loom band bracelet on her recent trip to New Zealand, external, and David Beckham, One Direction's Harry Styles and the Duchess of Cornwall have done the same.

A jokey YouTube rant against rubber band bracelets, external, posted by an American girl called Becca, has had more than two million hits.

Children use the looms, or their own fingers, to weave coloured bands into items such as bracelets, necklaces and charms. They use dozens of different designs, recommended on YouTube and by word of mouth, including the "fishtail", the "dragon scale" and the "inverted hexafish". More ambitious projects include skipping ropes, animal shapes and even a suit worn by US TV host Jimmy Kimmel, external.

Multicoloured bands sell for as little as £1.99 for 1,800. Rainbow Looms - frames used for knitting the bands - retail at under £20. In an age when the toy market is dominated by more complicated toys and expensive computer games, backed by marketing campaigns, how did they become so popular?

Rainbow Loom was invented in 2011 by Cheong Choon Ng, a Malaysian-born former seatbelt technology developer from Michigan, who noticed his daughters weaving elastic bands over their fingers to make bracelets. Ng tried it but his own fingers were too big, so he built himself a "loom" - a technology known to the clothing trade since at least the 15th Century - using pins and a wooden slab. His daughters were impressed with the more intricate patterns this allowed.

Ng developed a plastic version and set up a business manufacturing them, investing $10,000. He got a toyshop to stock his product and, after it sold out within a few hours, other stores took an interest. It spread from there and looms and bands can now be seen in schools and homes around the UK and US.

"It wasn't driven by advertising or big companies," says Richard Gottlieb, founder of consultants Global Toy Experts, external. "It's what I call the social network of the playground. It started out in a specific geographical location and just spread from there. You get these phenomena every few years. There's a difference between creating a product that sells and a phenomenon. There's a bit of magic about it."

A school in New York banned loom bands, external after reports they had caused playground fights. The Furness Academy in Cumbria did the same earlier this month, informing parents of the decision by text message. "They felt they wanted to nip it in the bud," says a spokeswoman. "Some of the children were throwing them around inappropriately. There were many tens of them around left around on classroom floors."

"It's part of the charm of these crazes that the kids find something they can do at school until they are banned," says Esther Lutman, assistant curator at the Museum of Childhood. "They keep pushing new stuff, particularly in the summer, when they spend more time in the playground together."

Concern over mess caused by discarded bands is echoed by the mother and blogger Big Fashionista, external, who complains that "these pesky little bands get in more places than they really should, my house is overrun with them". The US writer Hallie Sawyer, external describes Rainbow Loom as "Silly Bandz on crack" which will "someday clog up every landfill in America".

In the Philippines, an animal rights group, external has warned that "cute, but hard to digest rubber bands" can block the intestines of pets who eat eat those left lying on the floor. This does not seem to be a problem in the UK. "We've had no reports about this here," says an RSPCA spokeswoman.

Rainbow Loom is aimed at eight to 14-year-olds, but it has become popular among younger children too. "They are loads of fun and you can make loads of shapes and rainbow colours," says Emmie, seven, from Brighton. "Everyone in the playground is doing it," says Najwa, also seven. "I like doing dragon-scale bracelets."

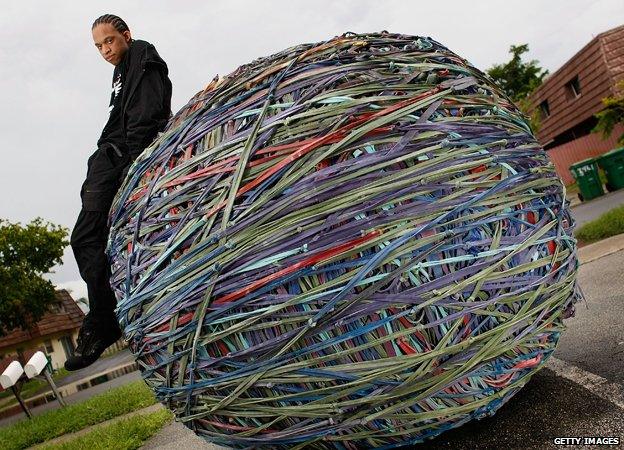

Rubber bands are hardly new. London businessman Stephen Perry took out the first patent in 1845, the stated use being to bind papers and letters. Children have long used them to make catapults and bored office workers sometimes bind them together to make bouncy balls.

Evolution of the rubber band

Vulcanised rubber patented in Britain in late 1843 by Thomas Hancock, with Charles Goodyear doing the same in the US a few weeks later

William Spencer is credited with beginning mass production of rubber bands in Ohio in the 1920s

A five-ton ball, consisting of 730,000 rubber bands, was created by Joel Waul and bought by Edward Meyer for Ripley's Believe It or Not in 2009, external

In 2011 Royal Mail revealed that postal workers in the UK got through two million red rubber bands per day

Similar crazes to Rainbow Loom have developed in recent years. Scoubidous, external - plastic strings twisted together to make jewellery - launched in France in the late 1950s. They returned to prominence in the mid-2000s and spread to other countries including the UK.

During the late 1980s, Slap Wraps, thin pieces of fabric-covered metal which curved into a bracelet when slapped against the wrist, were popular, the New York Times, external describing them as "basically a Venetian blind with attitude".

Rubber wristbands bearing the motto of the multiple Tour de France winner Lance Armstrong - "Live Strong" - were a popular item until his fall from grace over doping. The Eraselet, a similar-looking product which doubles up as an eraser, has sold more than two million units.

In the summer of 2010, Silly Bandz, external became a hit. They are plastic moulded into shapes such as animals, musical instruments and letters, and worn as jewellery, but the emphasis is more on collectability than creativity.

"Loom bands are bigger, "says Lutman "I would bracket them with marbles in the Victorian era, yo-yos in the 1930s and hula-hoops in the 1950s. They are quite cheap, which helps explain their spread around playgrounds. They are at their absolute peak now. Who knows what will be next?"

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.