Bosnia and WW1: The living legacy of Gavrilo Princip

- Published

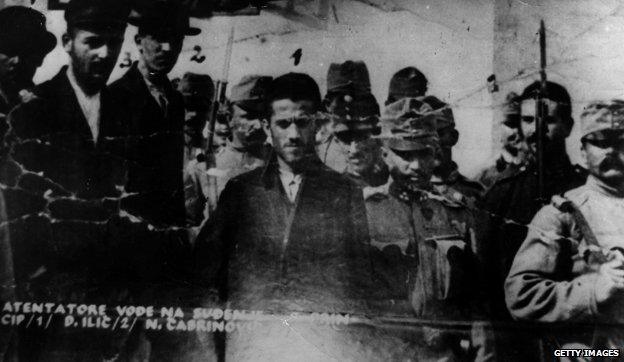

Tourists, historians and diplomats have been arriving in Sarajevo to commemorate the shots fired by a young Bosnian Serb assassin on 28 June 1914 - shots that sparked World War One. But the city and country are uneasy in the historical spotlight, as the tensions behind those events are still alive today.

Gavrilo Princip fired twice at close range into the open-topped car carrying the heir to the throne of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, Franz Ferdinand, and his wife Sophie. He could hardly miss - two of the bullets found their targets and the royal couple were killed.

After 37 days of increasingly paranoid diplomacy, the Great Powers went to war. The Austrians hoped this would solve the problem of Slavic separatism, and it did - but only after four years of war that destroyed their empire.

With such a momentous event to commemorate, you might have thought the city and national authorities would be filling the streets with historical re-enactments and using any available venue to stage cultural events exploring the many human stories and tragedies unleashed by the Sarajevo shooting.

But they are not.

The shot that sparked World War One

Archduke Franz Ferdinand and wife Sophie shot dead in their car by Gavrilo Princip on 28 June 1914 in Sarajevo

Princip one of seven members of Mlada Bosna (Young Bosnia), a Bosnian Serb terrorist organisation who want independence from Austria-Hungary

Austria responds angrily and declares war on Serbia, securing unconditional support from Germany

Russia announces mobilisation of its troops

Germany declares war on Russia, 1 August

Britain declares war on Germany, 4 August

Almost all the historical conferences and pan-European reconciliation concerts have been set up by outsiders, or on private initiatives.

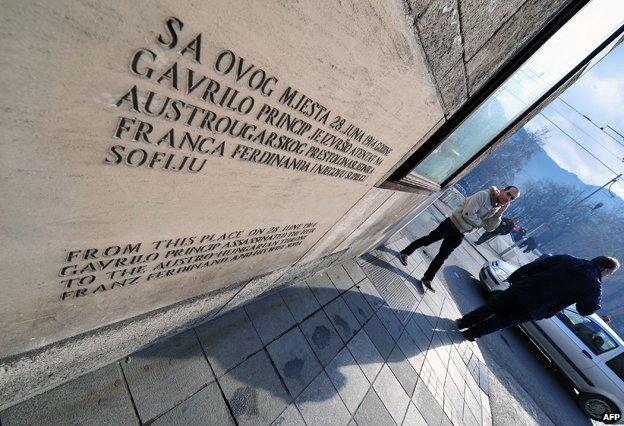

The reason can be guessed at by looking at the sign outside a building by the Miljacka River. This used to be the Muzej Mlada Bosna, the Young Bosnia Museum, set up after WW2 by Tito's Communists to glorify Princip and his co-conspirators as freedom fighters. Now the sign is a lesson in political correctness - Museum of Sarajevo 1878-1918. You need to be more historically aware than most of us to know those dates mark the start and finish of the Austro-Hungarian occupation of Bosnia.

Tour guide Vedran Grebo told me: "It's absolutely political. The different communities here - Bosniak Muslim, Orthodox Serb and Catholic Croat - just don't agree on what to call what Princip did, 'heroism' or 'terrorism'."

Although Princip claimed to be acting on behalf of all southern Slavs, in attempting to liberate Bosnia away from Austro-Hungary, it is principally among Serbs that he is lionised. Bosniaks and Croats had little desire a century ago for unification with Serbia - just as in the 1990s many were keen to break away from Serb-dominated Yugoslavia.

When I was reporting from Sarajevo during the siege that killed more than 11,000 from 1992 to 1995, the Young Bosnia museum was in range of sniper fire from the surrounding hills. But if you took your chance, you could still find a broken paving stone outside with footprints embedded, supposed to mark the spot where Princip took aim. "It was a treat for every young Yugoslav to come here on a school trip and stand in those heroic footprints," says Vedran Grebo. "Now they are gone."

The political arrangement left behind by the Dayton Peace Agreement ended the fighting in 1995. But it has not healed the divisions created by the nationalist ideologies on which that war was started, first in Slovenia and Croatia in 1991, and then most bloodily in Bosnia the following year. Inspired by Serbia's Slobodan Milosevic as he turned from Communism to nationalism, Bosnia's Serbs set about trying to unite Bosnia with Serbia, in an echo of Princip's dream. They failed, but Dayton gave them political control over just under half of the territory and a veto over national policy for Bosnia-Herzegovina.

Bosnian war 1992-1995

Sarajevo residents run from snipers in June 1992

Bosnian Serb nationalists are outvoted as Bosnian Muslims and Croats vote for independence in a 1992 referendum

War breaks out and Bosnian Serbs quickly take control of more than half the republic, laying siege to Sarajevo

UN safe havens for Bosnian Muslim civilians are created in 1993, including Sarajevo, Gorazde and Srebrenica

Bosnian Serb forces overrun Srebrenica in 1995 - Muslim men and boys are massacred

Nato air strikes against Serb positions help Muslim and Croat forces make big territorial gains, expelling thousands of Serb civilians

Dayton peace accord signed in Paris, creating one entity for Bosnian Muslims and Croats, the other for Serbs

That has hampered the development of Bosnia's economy and created space for corruption. Unemployment is 44% and infrastructure is creaky.

The inability to agree on the facts surrounding the events of 1914 is just another symptom of political failure, according to centre-left politician Dennis Gratz from the Nasa Stranka party.

"History creates emotions, and of course politicians here misuse emotional aspects of our history to cover their own incompetence in dealing with the real problems of our country. Parties based on ethnicity say, 'We have to protect ourselves against the others because they want to do bad things.' So they don't sit down together and make policy."

To try to teach history in Bosnia's schools is to wander into a political minefield, according to history teacher Senada Jusic. "As teachers we are supposed to teach facts and recognise that there are different interpretations. I do that when I'm talking about Princip. But I have met teachers from other parts of Bosnia, even other parts of Sarajevo, who say they can't do that. They have to say he was a hero."

Graffiti of Gavrilo Princip in Belgrade, Serbia. Text reads: "Our ghosts will wander through Vienna, stroll around the palaces and scare the masters."

While Bosnia itself, the scene of the shootings, remains trapped - "doomed," says Dennis Gratz - by unresolved history, in Serbia's capital, Belgrade, where Gavrilo Princip received his training and his gun, I found much more willingness to leave history in the past.

Student Marko Jovanovic told me Princip "did not do the smartest thing, when I see all the millions of people - Serbian, Austro-Hungarian, French, German, British, Russian, killed."

The view that Serbia may have been on the side of the victors in 1918 but did not "win the war" - is growing. "With one-fifth of the population killed, could you really call that nation a winner? And people for the first time are asking that question here," historian Slobodan Markovic told me.

In Sarajevo, historical emotions will be stirred up this week. Vedran Grebo took me to the mausoleum on a hillside where the bones of Gavrilo Princip, who died of TB in an Austrian prison, and his co-conspirators are laid. He read me the inscription, a quote from the Montenegrin poet Petrovic-Njegos: "Blessed is he who lives forever, he did not die in vain."

Politicians in Bosnia will keep Princip's memory alive while it suits them. Perhaps they should take note of the other inscription on the Mausoleum - the date of its construction, 1939, at the start of World War Two, which was itself a consequence of World War One.

Little wonder, perhaps, that the people of Sarajevo aren't overjoyed with the 1914 commemorations. They can't be sure Princip's legacy is all spent.

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.

Listen to the first BBC debate on the War that Changed the World on Saturday, broadcast from Sarajevo on the BBC World Service - or catch up afterwards on the BBC iPlayer