How Patio cola changed the world of fizzy drinks

- Published

Fifty years ago Diet Pepsi was first marketed, trying to fix a link in consumers' minds between sugar-free fizzy drinks and weight loss. But today, the very term "diet" on food and drink almost seems a little retro, writes Chris Stokel-Walker.

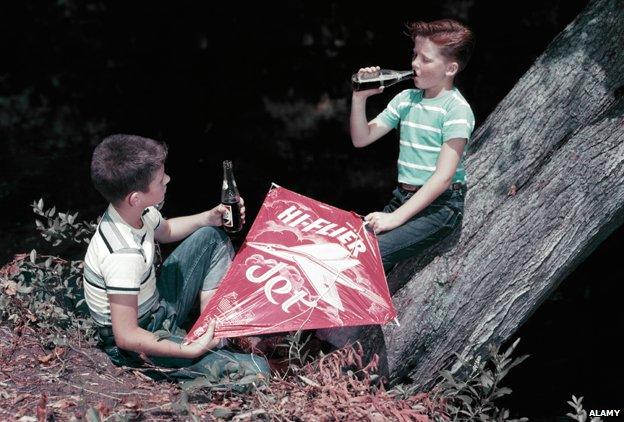

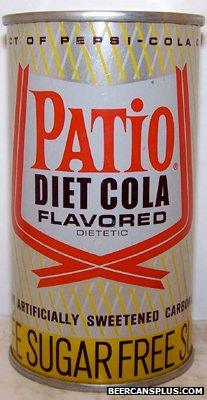

Fans of Mad Men may recognise Patio Diet Cola.

The product featured in the first few episodes of series three of the advertising agency drama, and is a point of dispute between Sterling Cooper staff members when PepsiCo reject a television commercial based on the film Bye Bye Birdie.

Patio was a real product and the year after its introduction in 1963 it was rebranded as Diet Pepsi. But Pepsi's move into diet drinks was inspired by an unusual source.

A soft drink produced for diabetic patients at New York's Jewish Sanitarium for Chronic Disease in the early 1950s called No-Cal ballooned in popularity, far beyond the customer base its maker expected. It turned out more than half the people buying No-Cal weren't diabetic - they were just watching their weight.

This caught the attention of Royal Crown, a cola maker, which introduced Diet Rite Cola in 1962. Their product was marketed towards the calorie-conscious as a dietetic product. The strategy worked - in three years, sales of diet drinks increased fivefold. Pepsi was forced to act.

But PepsiCo was not sure there was a big enough market for their diet drink, or that it would be successful. So they hedged their bets. They released the drink, but avoided connecting it to their main Pepsi brand, worried a potential failure could tarnish the brand they had spent years building. When they recognised the fad for diet food and drink wasn't disappearing, they renamed Patio.

But the creation of Diet Pepsi, and Diet Coke in the early 1980s, have not led to the proliferation of the term "diet" across lower-calorie food and drinks.

Diet foods are plentiful - the industry is worth £1.8bn in the UK, according to analyst Mintel, - but their branding is subtle. Wander a grocery aisle in today's supermarkets and there are plenty of reduced-calorie ready meals, prepared foods and canned and bottled drinks - but almost none of them use the word "diet".

The brand names are fuzzier and warmer than simply slapping "diet" on the label. In the UK, Tesco's reduced calorie and fat products are sold under the "Healthy Living" brand - previously this was called "Light Choices". Marks & Spencer use the "Fuller Longer" and "Count on us" brands to market their reduced calorie and fat foods. Sainsbury's healthier fare is emblazoned with the message "Be good to yourself".

In the US, Wal-Mart has the "Great for you" tag, and both it and Target sell third party products under the "Healthy Choice" banner.

There's a particular reason the supermarkets go down this route, says Marc David, a nutritional psychologist and founder of the Institute for the Psychology of Eating. "Health is a long-term proposition: if I'm eating junk food, I'm not thinking about the long-term. But if I'm sitting down at a meal, I'm thinking about my long-term health. There's a sense of empowerment to that - I can make choices and eat food that will make me feel healthier."

Modern consumers prefer to be inspired rather than chided. "Diet" has negative connotations. "People make decisions, especially in a supermarket environment, you're talking three to seven seconds, and they might only read six words on a weekly shop," says Simon Forster of branding agency Robot Food. Communication has to be very direct, and being aspirational sells.

"In many sectors the word 'diet' has evolved to 'light'," Forster says. "Some people could see 'diet' as off-putting."

David agrees: "Ironically, one might think of the term 'diet' as something heavy."

Pepsi and Coca-Cola have stuck with "diet", having built up brands, but they've experimented with other terms. In 1993, PepsiCo introduced Pepsi MAX, a sugar-free carbonated soft drink that targets a similar audience to those who drink Diet Pepsi. Combined, PepsiCo's sugar-free alternatives account for 68% of the company's total sales in the cola category.

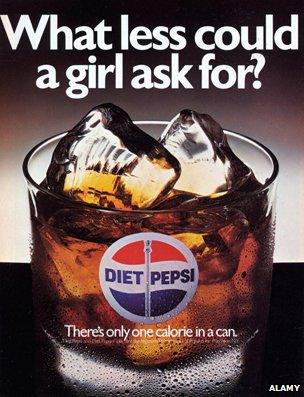

Coca-Cola produces Coke Zero alongside Diet Coke, with the two drinks aimed at different markets - the Coke company found young men were unwilling to buy Diet Coke, feeling the word "diet" was too nagging and feminine.

PepsiCo's advertising for its low- or no-calorie drinks is often geared specifically towards an enviable figure. One of its earliest slogans in the 1960s was "The girls girl-watchers watch, drink Diet Pepsi". The implication was that drinking Diet Pepsi would keep a woman slim and desirable. Even more recent adverts toe this line - a 1996 Brazilian Diet Pepsi billboard accentuates a model's slim waist with the tagline: "You drink and get nothing." A 2004 US advert portrayed a two-litre bottle of Diet Pepsi slinking off its label, so stick-thin is its figure.

The avoidance of the dreaded d-word can "strike a chord with a more demanding 'lifestyle-driven' consumer", believes Forster. PepsiCo introduced Pepsi Next, a drink with fewer calories than its regular cola, in 2012. Coca-Cola this month unveiled Coke Life, a drink that contains sugar and new natural sweetener stevia and has 89 calories per can, compared to 139 in normal Coke. The green cans, aimed at calorie and health-conscious consumers, will be on British shelves this autumn following trials in South America last year.

"Consumers demand additional benefit from products and if the product evokes an active lifestyle, along with the inherent benefit of having no sugar it's a win for sales, leaving 'diet' as a bland and slightly dated alternative," says Forster.

A quarter of the carbonated drink industry's US revenue comes from diet options, according to analysts IBISWorld. The average annual intake of fizzy drinks is dropping, with the average American drinking nearly a fifth less than a decade ago.

And while standard versions of soft drinks have retained roughly the same market share in the past decade, according to data collated by Beverage Digest, an industry magazine, diet drinks have lost ground. Diet Pepsi had a 5.8% market share in 2003, which had dropped to 4.5% 10 years later.

Despite the burgeoning concern over sugar in drinks, few will be pushing diet fizzy drinks as a healthy alternative. They damage your teeth and have even been associated with weight gain, external.

But the two big diet colas will long remain powerful brands.

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.