The women who serve in danger zones

- Published

Jane Marriott in Iran

For decades women were not allowed to join Britain's diplomatic service, but since the rules were changed they have gone on to represent their country in many of the world's conflict zones.

In November 2011, deputy ambassador Jane Marriott had to manage her staff and a crisis when hundreds of protesters stormed the British embassy in Tehran.

They stayed holed up in part of the embassy compound as a "baying mob" ransacked everything in sight, while the Iranian security forces did not initially intervene.

"I kept telling the team that everything would be fine and [concentrated on] setting out a plan of action," says Marriott.

She negotiated by phone with the Iranian authorities for them to get the crowd under control and out of the compound, while she and her staff stayed hidden. "We were calm but conscious that the crowd could turn on us if we were discovered," says Marriott, who is now the UK's ambassador to Yemen.

The demonstration followed the imposition of further British sanctions over Iran's nuclear programme.

Iranian protesters force their way into the British embassy in Tehran, 2011

The deputy ambassador and her staff were finally able to emerge after about eight hours and survey the extensive damage, which included the destruction of Marriott's beloved cello.

Up until just 70 years ago, Marriott would never have found herself making decisions in this kind of crisis.

It was only in 1946 that women were allowed to join the UK's diplomatic service. Historian Helen McCarthy, author of Women of the World: The Rise of the Female Diplomat, says opponents had argued that women could not deal with the rougher side of the job and would not be accepted or taken seriously by some governments.

Marriott, who has also served in Iraq and Afghanistan, believes she and other women diplomats have clearly disproved those arguments.

"I've very much enjoyed doing all these conflict postings. They're hard, they're dangerous, you have to have a constant awareness of risk and threat mitigation, but the secret is that these jobs are also the most fascinating because they are in countries that are in times of transition," says Marriott.

McCarthy says a number of women had served Britain abroad with distinction before women were formally admitted to the diplomatic service.

Gertrude Bell, an archaeologist, linguist and writer who had travelled extensively in the Middle East, was recruited in World War One to Britain's Arab Bureau in Cairo. It co-ordinated British intelligence, political and propaganda work across the region.

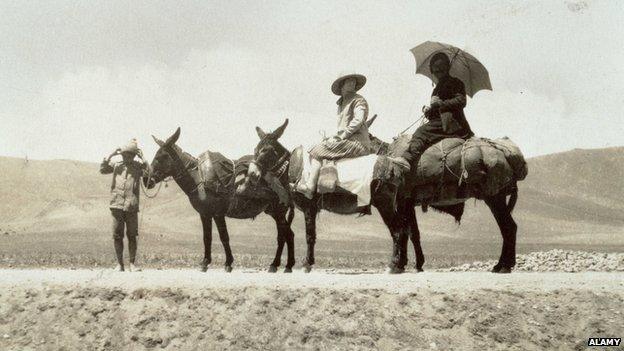

Gertrude Bell 1868-1926

Gertrude Bell with King Faisal of Iraq (second from right) in 1922

Sometimes referred to as the "uncrowned queen of Iraq" following her deep involvement with the country during the critical period of its birth.

Frequent traveller to the Middle East - published her first book about Syria in 1907

During WW1 her knowledge of the region was a vital source of information, and she was employed as an intelligence agent

Became one of Winston Churchill's closest advisers and was asked to help draw up the borders of the new nation of Iraq and help choose its first ruler, Prince Faisal

McCarthy says another woman in particular helped force open the doors of the diplomatic service.

Dame Freya Stark was recruited by the government - thanks to her fluent Arabic and knowledge of the region - to go to Yemen, Egypt and Iraq to drum up support for the UK during World War Two.

"She was very effective in creating a whole network of pro-British Arabs among the tribal leaders, sheikhs and businessmen in the countries she travelled in," says McCarthy.

In 1945 Stark wrote to the Foreign Office committee that was considering the admission of women, arguing in favour.

Freya Stark (centre) in Jabal al-Druze in what is now modern-day Syria

The committee overruled decades of objections - including the argument that if women were admitted it would mean there would be fewer diplomatic wives available to help with things such as embassy functions - and in 1946 the first women were recruited.

"It was a great breakthrough. You had to show that women could do the job," says Dame Margaret Anstee, who was one of a handful of women who joined the diplomatic service in 1948.

"On the one hand you had people who were nice to you, but rather patronising. On the other side there were some diehards who thought the admission of women was the beginning of the end of the world."

One senior official was like a character out of a Dickens novel, she remembers. "He was very tall and thin and elegant and smoked cigarettes with a long holder and was very elitist. He wrote with a quill pen.

"A colleague of mine had to clear a draft with him that she'd written. He looked up at her and said, 'Did you write this?' in some terms of amazement. She said, 'Yes', and he said, 'All of it?'," says Anstee.

She fell foul in 1952 of the "iniquitous" rule which meant that women had to resign if they got married. "It was something we had to accept in those days, but it was a terribly hard decision," says Anstee, who married another diplomat and followed him on a posting to the Philippines.

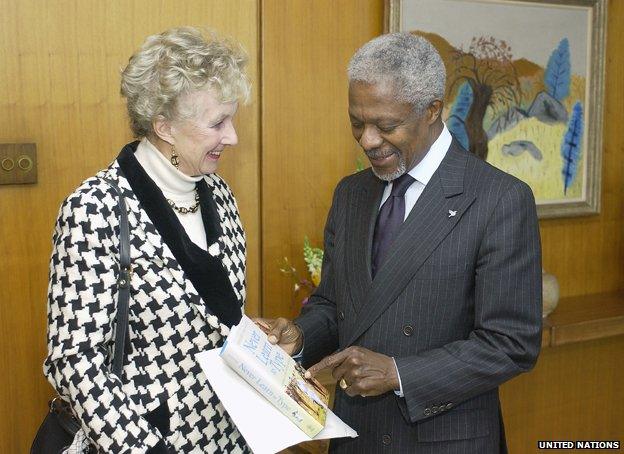

The marriage collapsed and with no income Anstee joined the UN as a local employee in the Philippines. She rose to become the first woman under-secretary general.

Dame Margaret Anstee with former UN secretary general Kofi Annan, 2003

McCarthy says this "marriage bar", which only ended in 1973, was responsible for the slow progress of women.

"The justification was that you couldn't expect a diplomatic husband to follow his wife around from post to post and so [women] would be less mobile and you would have to keep them in London or only post them occasionally to places in western Europe," says McCarthy.

Britain appointed its first female ambassador - Barbara Salt to Israel - in 1962, but she was unable to take up the position because of ill health. It took 14 years before another woman was appointed and Dame Anne Warburton became Britain's ambassador to Denmark.

"In Denmark there were more women in office than we had here," says Warburton.

Frances Guy says that when she joined the Foreign Office in 1985 it was the first year that equal numbers of men and women were recruited into the fast stream for senior management.

Guy was a political officer at the embassy in Sudan when there was an Islamist-led coup in 1989. In 2001, she became Britain's ambassador to Yemen - a country beset by tribal rivalries and home to al-Qaeda linked groups.

On one occasion there was a gun battle outside the embassy when the son of a tribal leader strongly objected to the fact that embassy security personnel had blocked off a road, meaning he would have to take a detour.

"I and one other person were the only people in the building and there were some bullets coming through the window," says Guy. They were not injured.

The families of embassy staff were evacuated twice because of threats from militants to the embassy and Westerners. She was the ambassador to Lebanon in 2008.

Frances Guy in Lebanon

There were barriers in Yemen. "When they see you officially they're seeing you as your position. You don't have a sex. Unofficially, they don't deal with you because you're not a man," says Guy.

"Lebanon has slightly more complicated attitudes towards women. By the time I left [in 2011] we were 12 female ambassadors so the politicians couldn't ignore us, but when I first went they were little bit more patronising," she says.

Despite such experiences, both Guy and Marriott agree that there are some advantages to being a woman diplomat, such as being able to talk to the female population when local custom prevents male diplomats from doing so.

"I remember in Iraq having conversations with male sheikhs about security and then later on going through to the kitchen and talking to the women. When there were tribal battles later on in the year, I knew who was married to whom and so I knew why the tribes were allying as they did," Marriott says.

Total equality has not yet been achieved. McCarthy points out that only one in five heads of British diplomatic missions overseas is a woman, while only 25% of senior managers at the Foreign and Commonwealth Office are women.

Jane Marriott and Helen McCarthy spoke to World Update on the BBC World Service.

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.