India's long, dark and dangerous walk to the toilet

- Published

The danger faced by women going to the toilet outdoors in rural India was made clear last month when two girls were ambushed, gang-raped and hanged from a tree. But defecation outside is normal for most Indian villagers - so how do they manage?

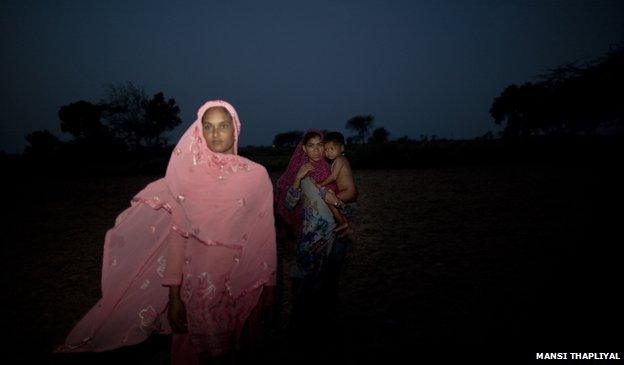

Less than 50 miles from India's capital Delhi, in a village called Kurmaali the women walk out to the fields twice a day - at the crack of dawn and the onset of dusk.

The fields are the only toilet most of them have ever known. Only 30 of the 300 homes in the village have their own private facilities, and none have drainage.

They walk out together, in groups, for safety. It takes about 15 minutes. Then they separate and space out for a little privacy.

Kailash, aged 38, wakes her three daughters up at 04:00 every morning. Each takes a bottle of water, and they set off.

"We always go in groups. I would never let my girls go on their own," Kailash says.

Her youngest daughter, 18-year-old Sonu, adds: "We go straight to the toilet and back. Never deviate. Never go alone. And if we see a boy, we shout at him."

It is important to tread carefully. Once the crops are cut and the fields are bare the whole ground space is open for anyone to use. It's literally like an open toilet.

During sowing and harvesting, the fields are out of bounds. Then one has to walk for another 15 minutes, to an uncultivated area. The exercise that normally takes 45 minutes to an hour stretches to an hour and 15 minutes, or more.

Darkness gives the women cover, and a degree of privacy, which is very important to them, but it in some ways it makes them more vulnerable. They are keen to get the process over as quickly as possible.

The unspoken rule is that the men go to the toilet only at dawn, but boys sometimes break this rule, in order to harass or molest members of the opposite sex. The women tell stories of catcalling, and groping - though will never admit that has happened to them, only to others.

Sonu's advice, if a boy appears? "Always be aggressive."

Her elder sister Seema says she would not shy from giving the boys a slap if they dared touch her sisters.

The group tells a story about one woman from the village who foolishly went to the fields alone, and suddenly found herself illuminated by the lights of a passing lorry. The lorry stopped, and the driver got out. The woman was forced to run for safety.

The mother of one of the girls found hanged in Uttar Pradesh confided to me that she always accompanied her daughter to the fields but this one time she had let them go alone - a decision she said she'd always regret.

No toilet paper is ever used in the village, only water, though after returning from the fields, the women usually have a proper wash with soap.

Then there is a long wait until the next trip to the open-air toilet after darkness falls in the evening, some 14 or 15 hours later.

The women have no choice but to contain any desire to urinate or defecate, if necessary for hours on end.

But last year Sonu fell sick with an upset stomach.

"She needed a toilet urgently, so, I filled water in a bottle and took her to the fields during daytime," says Kailash. "I stayed with her for three hours. I spread a sheet under a tree, so she could rest every few minutes, we had to stay till she felt that she wouldn't need to go to the toilet anymore."

They don't like to talk about it, but the women of Kurmaali eventually admit that in cases of emergency, children or elderly people may use a kind of toilet pan inside the house. It's hard for them to disinfect it though, so after a few days it begins to smell and has to be thrown away. They make clear how disgusting they find this topic.

In fact, many think of open-air toilets as the natural way of defecation.

Seema, Kailash's eldest daughter, spent a few years at a boarding school, which had an enclosed private toilet. She quickly became accustomed to it, but nonetheless regards this kind of toilet as a necessity born out of modern living.

"Our school and hostel were in big buildings, there were no fields around them, so they had to build toilets," she says.

At the only school in Kurmaali itself, for some 300 day pupils, I found two toilets but they were clearly not in use. One had no door, the other was full of bricks and other rubbish.

When I asked one of the school governors why this was, he questioned why anyone would need a toilet. The school was right next to the fields, he pointed out. This infuriated the women accompanying me. The boys might be able to use the fields in daylight, they pointed out, but not the girls.

Deadly cost

In May, two teenage girls in the northern state of Uttar Pradesh were gang-raped and hanged from a tree while going to the toilet outdoors

The crime prompted protests against state government (pictured) and claims that police officers refused to search for victims

A senior police official in Bihar claimed in 2013 that more than 400 rapes in the state would have been avoided if victims had had home sanitation

Most of the men in the village work as daily labourers, or drivers. A few work in the fields. One of the few that has a private toilet is Santraj, a mason, who lives next door to Kailash.

He built it eight years ago, at a cost of 10,000 rupees (£100), double the village's average monthly wage. The toilet sits on top of two 10ft-deep pits, which drain in such a way, he says, that there is no foul smell. The pits will need to be emptied one day, but should last 10 years.

But why have Santraj and a few others got a toilet when the vast majority of the villagers have not?

He says it's because he has only four children, while most families have at least half a dozen to support.

Also, he points out, the lack of a toilet doesn't usually bother men.

"Men can go anywhere, any time," he says. "It is only the women who need protection and cover."

Even in the cities, it is common to see men in India urinating in public against a wall.

In Kurmaali it is interesting to note how the families spend their limited incomes.

The streets are dotted with motorbikes and the occasional car, luxury items mostly acquired as part of a dowry.

Kailash's dowry did not include a motorbike, but her husband has purchased a television set and a satellite dish - even though the electricity comes on for four hours every day at most.

He could probably have afforded a toilet, with the help of a government grant available for this purpose. But while Kailash's husband treats his wife well, doesn't drink alcohol or abuse her physically, a toilet was not his priority.

"Toilets are not so important for men," Kailash says.

"And I can't throw a tantrum about this, women don't do that here."

Divya Arya reported from Kurmaali for the Fifth Floor, on the BBC World Service. Catch up on the BBC iPlayer or download the podcast.

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.