Viewpoint: Should gay men and lesbians be bracketed together?

- Published

Lesbians and gay men have long campaigned alongside each other. But are they wrongly bracketed together, asks Julie Bindel.

"We have absolutely nothing in common with gay men," says Eda, a young lesbian, "so I have no idea why we are lumped in together."

Not everyone agrees. Since the late 1980s, lesbians and gay men have been treated almost as one generic group. In recent years, other sexual minorities and preferences have joined them.

The term LGBT, representing lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender, has been in widespread use since the early 1990s. Recent additions - queer, "questioning" and intersex - have seen the term expand to LGBTQQI in many places. But do lesbians and gay men, let alone the others on the list, share the same issues, values and goals?

Anthony Lorenzo, a young gay journalist, says the list has become so long, "We've had to start using Sanskrit because we've run out of letters."

Bisexuals have argued that they are disliked and mistrusted by both straight and gay people. Trans people say they should be included because they experience hatred and discrimination, and thereby are campaigning along similar lines as the gay community for equality.

But what about those who wish to add asexual to the pot? Are asexual people facing the same category of discrimination. And "polyamorous"? Would it end at LGBTQQIAP?

There is scepticism from some activists. Paul Burston, long-time gay rights campaigner, suggests that one could even take a longer formulation and add NQBHTHOWTB (Not Queer But Happy To Help Out When They're Busy). Or it could be shortened to GLW (Gay, Lesbian or Whatever).

An event in Canada is currently advertising itself as an "annual festival of LGBTTIQQ2SA culture and human rights", with LGBTTIQQ2SA representing "a broad array of identities such as, but not limited to, lesbian, gay, bisexual, transsexual, transgender, intersex, queer, questioning, two-spirited, and allies". Two-spirited is a term used by Native Americans to describe more than one gender identity.

Gay men and lesbians have always faced different challenges.

Until 1967 consenting sex between men, of any age, was criminalised in the UK. Following decriminalisation, prejudice prevailed, with police entrapment operations to seek out men "cottaging" - having sex in public toilets and parks - creating fear and insecurity.

More from the Magazine

Twenty-one-year-old Jenni Goodchild does not experience sexual attraction, but in an increasingly sexualised society what is it like to be asexual?

"For me it basically just means that I don't look at people and think 'hmm yeah I'd have sex with you,' that just doesn't happen," says Jenni.

A student in Oxford, Jenni is one of the estimated 1% of people in the UK who identify themselves as asexual. Asexuality is described as an orientation, unlike celibacy which is a choice.

Lesbianism was never criminalised, but lesbians suffered a different and equally pernicious form of discrimination. When married women fell in love with another woman and their marriages ended, they invariably lost custody of their children, even when the father was known to be violent.

I came out as a lesbian aged 15 in 1977. At that time, neither the law nor the majority of heterosexuals protected or defended us. It was the heyday of the Gay Liberation Front (GLF) and lesbians and gay men worked together to fight for the most basic of rights - an end to discrimination in the workplace, violence in the streets and schools, and the recognition that being lesbian or gay was not an illness.

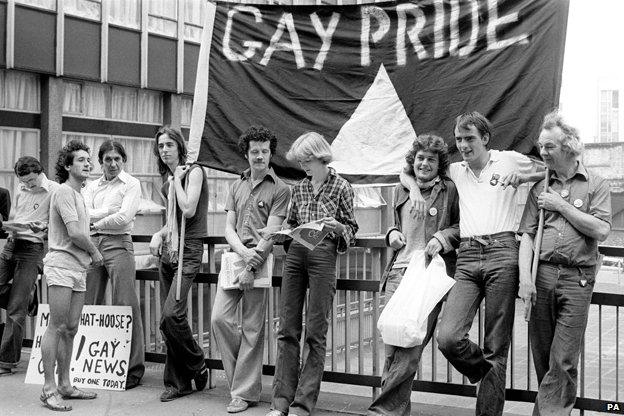

Gay Pride demonstration in London, 1977

There were so few of us able to be out and proud that gay women and men stuck together. But by the end of the 1970s, most of the lesbians had walked out of GLF. One founder member, who asked not to be named, says: "We were fed up with sexism from the very men who should know better."

During the next few years lesbians, including myself, fought for women's liberation as well as lesbian and gay rights. Some gay men drifted away from campaigning, external.

Then, in the mid 1980s came the Aids crisis, and the appalling anti-gay prejudice and hate prompted by the prevailing myth that Aids was a "gay plague". Building on the homophobic climate, the Thatcher government introduced pernicious new legislation known as Section 28 of the Local Government Act 1986. It became law on 24 May 1988. This amendment made it illegal for local authorities to "promote homosexuality" in state schools, perpetuating the idea that homosexuality destroys traditional family values.

When Section 28 became law, for the first time, lesbians and gay men were being targeted by the same legislation.

But do we really experience homophobia in the same way? This was one of the questions I have asked in a series of online surveys, disseminated through the gay and mainstream press, during the research for my book.

The surveys, completed by 9,500 gay men, lesbians and heterosexual people in total, included the question: "Do lesbians and gay men suffer homophobia in the same or different ways?" More than two-thirds of both groups said no, they did not believe that lesbians and gay men have the same experience of bigotry.

Section 28

Section 28 of the Local Government Act 1988 stated that local authorities "shall not intentionally promote homosexuality or publish material with the intention of promoting homosexuality" or "promote the teaching in any maintained school of the acceptability of homosexuality as a pretended family relationship"

Introduced by Conservative MP Jill Knight who said she was concerned for "parents who strongly objected to their children at school being encouraged into homosexuality and being taught that a normal family with mummy and daddy was outdated".

According to gay pressure group Stonewall, which was formed to oppose it, Section 28 made teachers "confused about what they could and could not say and do... Local authorities were unclear as to what legitimate services they could provide for lesbian, gay and bisexual members of their communities".

Section 28 was repealed in Scotland in 2000 and in England and Wales in 2003 - a number of senior Conservatives later said the legislation had been "a mistake", external.

Are gay men and lesbians cut from the same cloth? Yes, says Jane Czyzselska, editor of the lesbian magazine Diva, but only in terms of some experiences of discrimination. When the issue of sexism is factored in, the answer must be no: "Lesbians suffer the double whammy of sexism and homophobia, because we are punished for transgressing traditional gender behaviours and expectations." This type of abuse, which Czyzselska names, "lesbophobia", can lead to a variety of psychological responses, including self-harm, mental health issues, substance misuse and eating disorders.

One significant difference between lesbians and gay men is that of the visibility of the ageing population. Researcher Jane Traies conducted a study entitled The Lives of British Lesbians Over Sixty, external. Traies found that older lesbians are under-represented not only in popular culture and the media, but also in academic research, hidden from view by a particular combination of prejudices that renders them unrepresentable.

Older lesbians: Under-represented in popular culture and the media?

Older gay men are, however, represented. One example of this is the ITV sitcom Vicious, starring Ian McKellen and Derek Jacobi.

It is wrong to assume that gay men are not sexist towards their lesbian sisters. According to Lorenzo, there is a significant problem in the gay community with misogyny. I and other lesbians have experienced this first hand.

Whatever our differences - and there are many - until we are truly free from the reality of bigotry, lesbians and gay men will need to continue to work together.

"We are stronger together than apart," says Lisa Power, co-founder of the gay rights charity Stonewall. "Our homophobic enemies generally don't distinguish between us in their attacks - and while I agree with many feminist arguments and will always call myself a feminist, sexism is not the only form of oppression out there and we have to make alliances."

Now that lesbians and gay men in the UK have full legal equality, only time will tell whether we are truly free from homophobic bigotry, and whether old alliances will need to be reformed, or if we will finally go our separate ways.

One thing, however, seems certain. LGBTQQI will continue to be added to until the only person not represented in the list will be a straight, monogamous man.

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.