Will today's children die earlier than their parents?

- Published

It's often said that today's children will have shorter average life spans than their parents, because so many suffer from obesity. But there is another view that says they will live longer - at the risk of spending their twilight years in poor health.

The idea that children alive today will die younger than their parents has been popularised by Michelle Obama, external and Jamie Oliver, external - but the assertion that they "may on average, live less healthy and possibly even shorter lives than their parents" originates in scholarly research, external.

Not all experts are convinced, however.

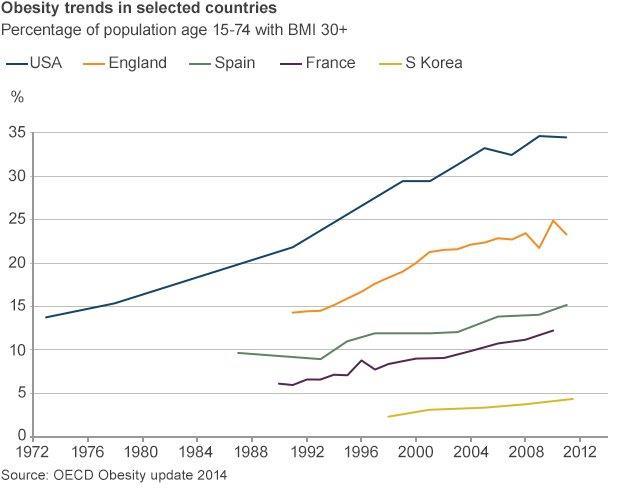

It's true that the number of people who are obese now is higher than in the past. Figures published in the Lancet earlier this year put the figure at 2.1bn worldwide, up from 875 million in 1980.

It's also true that obesity-related illnesses have been on the rise. It was reported this week that the UK is suffering a "national health emergency" because of the numbers being diagnosed with Type 2 diabetes, an illness which is often linked to obesity.

But the risk of dying from heart attacks and strokes, both associated with obesity, is in fact lower than in previous decades, according to a leading expert in the field.

"If you take Britain as an example, the probability of dying from the sorts of things caused by being overweight has gone down by a factor of four," says Sir Richard Peto, professor of medical statistics at Oxford University.

"If you go back 30 years then the chance we would die from a heart attack or stroke and diseases like that in middle age was 16% whereas it was 4% in 2010."

This trend is replicated in most parts of the world, in part because the treatment of heart problems is now much better than it used to be.

But some people think that being fatter may actually lengthen rather than shorten life.

Katherine Flegal, an epidemiologist at the National Centre for Health Statistics in Hyattsville Maryland, and her team analysed 97 studies into causes of death and concluded that people deemed "overweight" by international standards were 6% less likely to die than those of "normal" weight.

People are considered overweight if they have a body mass index (BMI) over 25 and obese with a BMI over 30.

Flegal's paper, published in the American Medical Journal in January last year, says it's possible that overweight people get better medical care - either because they show symptoms of disease earlier or because they're screened more regularly for chronic diseases, such as diabetes or heart disease.

It drew a hostile response from some public health experts, who have been advising people for decades to watch their weight.

A number of other researchers, on the other hand, have embraced Flegal's work and see it as the latest illustration of what is known as the Obesity Paradox - the notion that there is an inverse relationship between body fat and risk of death.

At least one study has suggested that heavier people are more likely to survive certain operations, external.

Fat or not, people around the world are likely to live longer than previous generations, says Peto.

"If you're not in the middle of a war, HIV epidemic or drinking gallons of vodka then overall death rates are going down and they are going down very fast," he says.

"The probability of dying before age 50 worldwide is half what it was 40 years ago."

Of course there are differences between countries. Forty years ago more than 36% of people died before their 50th birthday in Iran, whereas now it's only 6%, Peto points out. On the other hand, in some countries of sub-Saharan Africa there has been very little change.

There are a variety of different reasons for lengthening life expectancy, including better vaccination programmes and drugs, cleaner water, better trained midwives and people stopping smoking.

But though we may live longer our quality of life may be low.

According to research led by Christopher Murray, director of the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation at the University of Washington in Seattle, Americans often have to cope with a range of medical problems during those extra years of life.

They are "not necessarily in good health", he told the Wall Street Journal, external.

Obesity, diabetes, kidney disease and neurological conditions like Alzheimer's are all on the rise, both in the US and in much of the developed world.

So while we can expect extra years, they may not necessarily be golden - which is itself a good reason to stay away from the pies.

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.