The smuggled stone that was once more precious than gold

- Published

Myanmar, also known as Burma, is one of the world's largest Jade producers - but with trade bound by international sanctions, many of the precious gemstones are smuggled out of the country.

At first, I think it's a waterfall. A wave of liquid sound comes towards me over the brackish waters of the Irrawaddy River.

As I get closer, crossing a bridge beside a flock of orange-robed monks, the wash of noise becomes louder, more crystalline. I'm in Mandalay, northern Myanmar, a bustling city of a million people, and the sound is the clack and rattle of hundreds of thousands of precious stones in the world's largest jade market.

I approach the market's entrance past workshops where teenage boys, cigarettes drooping from their lips, carve raw lumps of jade on viciously spinning wheels.

The market itself is a vast and baffling warren, row after row of traders with their iridescent stones laid out on white trays.

At least half the traders are Chinese, and the voices that ring out over the clatter of sorting stones mix Mandarin and Burmese as they vie for business.

Estimates place the value of Myanmar's jade trade at more than $8bn (£4.7bn) a year. Most of the jade goes to China, whose presence in Myanmar has been growing at a precipitous rate since the end of the military dictatorship in 2011.

As I walk along one of the market's narrow alleys, side-stepping a slushy pile of betel nut pith, I see a Chinese trader, a woman in an embroidered skirt and Elton John T-shirt, fix a loupe to her eye to inspect a small pile of luminous green stones.

She's haggling with a young man. We'll call him Breng Mai, a pseudonym for reasons which will become clear. He's from Kachin State, the semi-autonomous region in the far north of the country.

The story of Burmese jade is inextricably tied to the turbulent history of Kachin, a once-lush country of rolling hills and steep ravines that rubs borders with India's Nagaland.

The Kachin Independence Army (KIA) fought a long and bloody war against the Burmese government, with an official ceasefire declared in 1994, but tensions and outbreaks of violence persist, with Myanmar's security services asserting a heavy presence in the area.

While the roadblocks and curfews may help keep the uneasy peace, they also ensure the government maintains control over the jade business.

Later I meet Breng Mai in his aunt's grocery store in downtown Mandalay. He's 23, absurdly handsome with a voguish blonde streak in his spiked hair. He's wearing a KIA T-shirt. The shop is bare and dingy, a single bulb hanging from the roof.

On the dusty counter are eggs, toothpaste, joss sticks and prawn crackers. Breng Mai leads me down a corridor, through a curtained doorway and into a back room, the centre of his smuggling empire.

It's like the planet Krypton, great mounds of jade dimly glowing.

"It is all chinjalu," he tells me, a Kachin word for jade of the highest clarity and quality - known elsewhere as "imperial jade". The shop is a front, run by his aunt as a warehouse for Breng Mai's illicit operations.

Sipping tea by the piles of precious stones, Breng Mai tells me he went into the jade mines aged 15.

"Although some working there were as young as eight," he says, "it was dangerous. There were regular avalanches. In one, our whole camp was swept away. I damaged my legs but my best friend was killed."

To trade legally, jade miners have to pay a tax to the government.

"Smuggling makes my profits much higher," Breng Mai says.

"I drive a beer truck from Hpakan to Mandalay every few weeks. The barrels in the middle of the van are full of jade. The government carries out raids every so often, but so far I've been lucky," he adds.

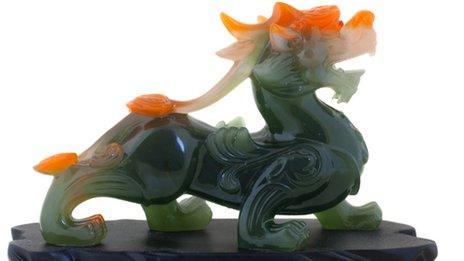

Jade, the royal gem

Jade is found in many colours including green, white, grey, black, yellow, orange and violet

It has been known to Man for 7,000 years but in prehistoric times was used for tools and weapons because it is so tough

Often called the royal gem in China where it was prized by emperors

Mayas and Aztecs in Central America valued it more highly than gold

Jade is a generic term for two different gems, nephrite and jadeite

While the West has largely lifted sanctions against Myanmar in the wake of the tentative steps towards democracy taken by the government of Thein Sein, a ban on jade trading still exists.

Conditions in the mines are abysmal, with the US government stating the jade business "contributes to human rights abuses and undermines Burma's democratic reform process".

While foreigners are not officially allowed to mine jade, Breng Mai tells me most of the major operations are now run by the Chinese.

"The Chinese pay the miners a lot more, but the conditions there are even worse," he says.

Kachin's formerly verdant hills are now scarred and treeless.

"When the Chinese are finished with Kachin State, there will be no jade left. Already mines that were rich 10 years ago are running out," he says.

Until that day, the stalls of Mandalay's labyrinthine jade market will continue to chime with the clatter of precious stones, the call of Chinese and Burmese voices.

As I leave, Breng Mai hands me a small sliver of dark jade. "For luck," he says, "it has worked for me."

How to listen to From Our Own Correspondent, external:

BBC Radio 4: Saturdays at 11:30 and some Thursdays at 11:00

Listen online or download the podcast.

BBC World Service: Short editions Monday-Friday - see World Service programme schedule.

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.

- Published16 November 2012

- Published26 May 2023