The virus detective who discovered Ebola in 1976

- Published

Nearly 40 years ago, a young Belgian scientist travelled to a remote part of the Congolese rainforest - his task was to help find out why so many people were dying from an unknown and terrifying disease.

In September 1976, a package containing a shiny, blue thermos flask arrived at the Institute of Tropical Medicine in Antwerp, Belgium.

Working in the lab that day was Peter Piot, a 27-year-old scientist and medical school graduate training as a clinical microbiologist.

"It was just a normal flask like any other you would use to keep coffee warm," recalls Piot, now Director of the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine.

But this thermos wasn't carrying coffee - inside was an altogether different cargo. Nestled amongst a few melting ice cubes were vials of blood along with a note.

It was from a Belgian doctor based in what was then Zaire, now the Democratic Republic of Congo - his handwritten message explained that the blood was that of a nun, also from Belgium, who had fallen ill with a mysterious illness which he couldn't identify.

Piot (right), at the Institute of Tropical Medicine, Antwerp in 1976

This unusual delivery had travelled all the way from Zaire's capital city Kinshasa, on a commercial flight, in one of the passengers' hand luggage.

"When we opened the thermos, we saw that one of the vials was broken and blood was mixing with the water from the melted ice," says Piot.

He and his colleagues were unaware just how dangerous that was. As the blood leaked into the icy water so too did a deadly unknown virus.

The samples were treated like numerous others the lab had tested before, but when the scientists placed some of the cells under an electron microscope they saw something they didn't expect.

"We saw a gigantic worm like structure - gigantic by viral standards," says Piot. "It's a very unusual shape for a virus, only one other virus looked like that and that was the Marburg virus."

The Marburg virus was first recognised in 1967 when 31 people became ill with haemorrhagic fever in the cities of Marburg and Frankfurt in Germany and in Belgrade, the capital of Yugoslavia. This Marburg outbreak was associated with laboratory staff who were working with infected monkeys imported from Uganda - seven people died.

Piot knew how serious Marburg could be - but after consulting experts around the world he got confirmation that what he was seeing under the microscope wasn't Marburg - this was something else, something never seen before.

"It's hard to describe but the main emotion I had was one of real, incredible excitement," says Piot. "There was a feeling of being very privileged, that this was a moment of discovery."

News had reached Antwerp that the nun, who was under the care of the doctor in Zaire, had died. The team also learnt that many others were falling ill with this mysterious illness in a remote area in the north of the country - their symptoms included fever, diarrhoea and vomiting followed by bleeding and eventually death.

Two weeks later Piot, who had never been to Africa before, was on a flight to Kinshasa. "It was an overnight flight and I couldn't sleep. I was so excited about seeing Africa for the first time, about investigating this new virus and about stopping the epidemic."

The journey didn't end in Kinshasa - the team had to travel to the centre of the outbreak, a village in the equatorial rainforest, about 1,000km (620 miles) further north.

"The personal physician of President Mobutu, the leader of Zaire at that time, arranged a C-130 transport aircraft for us," recalls Piot. They loaded a Landrover, fuel and all the equipment they needed on to the plane.

When the C-130 landed in Bumba, a river port situated on the northernmost point of the Congo River, the fear surrounding the mysterious disease was tangible. Even the pilots didn't want to hang around for long - they kept the airplane's engines running as the team unloaded their kit.

"As they left they shouted 'Adieu,'" says Piot. "In French, people say 'Au Revoir' to say 'See you again', but when they say 'Adieu' - well, that's like saying, 'We'll never see you again.'"

Standing on the tarmac watching the plane leave, facing a deadly unknown virus in an unfamiliar place, some people might have regretted the decision to go there.

"I wasn't scared. The excitement of discovery and wanting to stop the epidemic was driving everything. We heard far more people were dying from the disease than we originally thought and we wanted to get to work," Piot says.

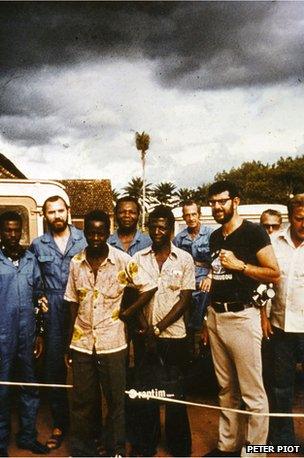

Piot (second from left) and the team in Yambuku in 1976

The curiosity and sense of adventure that brought Piot to this point had been ignited many years earlier when he was a young boy growing up in a small rural village in the Flanders region of Belgium.

A museum near Piot's home was dedicated to a local saint who worked with leprosy patients, and it was here that he got his first glimpse into the world of disease and microbiology.

"I decided one day to cycle to the museum. The old pictures I saw there of those suffering from leprosy fascinated me," he says. "That sparked my interest in medicine - it gave me a thirst for scientific knowledge, a desire to help people and I hoped it would give me a passport to the world."

It did give Piot a passport to the world. The team's final destination was the village of Yambuku - about 120km (75 miles) from Bumba, where the plane had left them.

Yambuku was home to an old Catholic mission - it had a hospital and a school run by a priest and nuns, all of them from Belgium.

"The area was beautiful. The mission was surrounded by lush rainforest and the earth was red - the nature was incredibly rich but the people were so poor," says Piot. "Joseph Conrad called that place 'The Heart of Darkness', but I thought there was a lot of light there."

The beauty of Yambuku belied the horror that was unfolding for the people that lived there.

When Piot arrived, the first people he met were a group of nuns and a priest who had retreated to a guesthouse and established their own cordon sanitaire - a barrier used to prevent the spread of disease.

There was a sign on the cord, written in the local Lingala language that read, "Please stop, anybody who crosses here may die."

"They had already lost four of their colleagues to the disease," says Piot. "They were praying and waiting for death."

Piot jumped over the cordon and told them that the team would help them and stop the epidemic. "When you are 27, you have all this confidence," he says.

The nuns told the newly arrived scientists what had happened, they spoke about their colleagues and those in the village who had died and how they tried to help as best they could.

The priority was to stop the epidemic, but first the team needed to find out how this virus was moving from person to person - by air, in food, by direct contact or spread by insects. "We had to start asking questions. It was really like a detective story," says Piot.

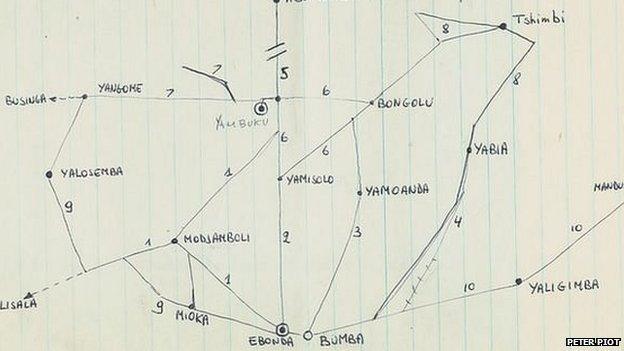

To investigate the spread of the virus the team drew maps and plotted each village they visited

These were the three questions they asked:

•How did the epidemic evolve? Knowing when each person caught the virus gave clues to what kind of infection this was - from here the story of the virus began to emerge.

•Where did the infected people come from? The team visited all the surrounding villages and mapped out the number of infections - it was clear that the outbreak was closely related to areas served by the local hospital.

•Who gets infected? The team found that more women than men caught the disease and particularly women between 18 and 30 years old - it turned out that many of the women in this age group were pregnant and many had attended an antenatal clinic at the hospital.

The mystery of the virus was beginning to unravel.

The team then discovered that the women who attended the antenatal clinic all received a routine injection. Each morning, just five syringes would be distributed, the needles would be reused and so the virus was spread between the patients.

"That's how we began to figure it out," recalls Piot. "You do it by talking, looking at the statistics and using logical deduction."

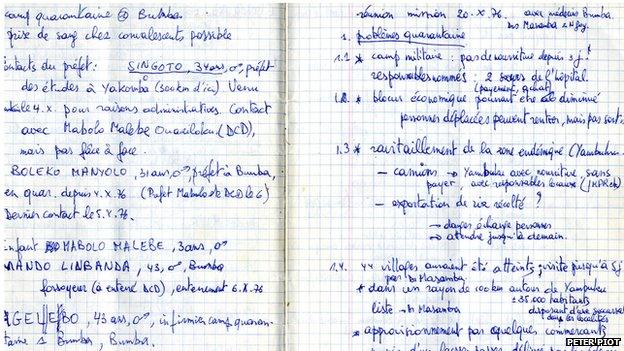

Many people were interviewed and detailed notes were taken during the investigation

The team also noticed that people were getting ill after attending funerals. When someone dies from Ebola, the body is full of the virus - any direct contact, such as washing or preparation of the deceased without protection can be a serious risk.

The next step was to stop the transmission of the virus.

"We systematically went from village to village and if someone was ill they would be put into quarantine," says Piot. "We would also quarantine anyone in direct contact with those infected and we would ensure everyone knew how to correctly bury those who had died from the virus."

The closure of the hospital, the use of quarantine and making sure the community had all the necessary information eventually brought an end to the epidemic - but nearly 300 people died.

Piot and his colleagues had learned a lot about the virus during three months in Yambuku, but it still lacked a name.

"We didn't want to name it after the village, Yambuku, because it's so stigmatising. You don't want to be associated with that," says Piot.

The team decided to name the virus after a river. They had a map of Zaire, although not a very detailed one, and the closest river they could see was the Ebola River. From that point on, the virus that arrived in a flask in Antwerp all those months earlier would be known as the Ebola virus.

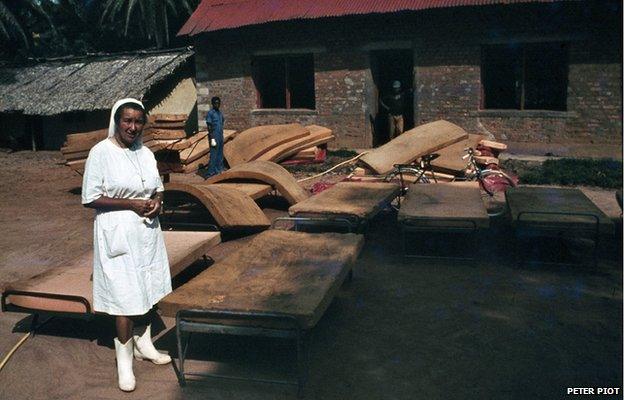

The Ebola River in 1976

In February 2014, Piot returned to Yambuku for only the second time since 1976, to mark his 65th birthday. He met Sukato Mandzomba, one of the few who caught the virus in 1976 and survived. "It was fantastic to meet him again, it was a very moving moment," says Piot.

Back then, Mandzomba was a nurse in the local hospital and could speak French so the pair had managed to build up a rapport. "He's still living in Yambuku and still working in the hospital - he's now running the lab there and it's impeccable. I was really impressed," Piot says.

Piot and Mandzomba in Yambuku, February 2014

It's 38 years since that initial outbreak and the world is now experiencing its worst Ebola epidemic ever. So far more than 600 people have died in the West African countries of Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone. The current situation has been called unprecedented, the spread of the disease across three countries making it more complicated to deal with than ever before.

In the absence of any vaccine or cure, the advice for this outbreak is much the same as it was in the 1970s. "Soap, gloves, isolating patients, not reusing needles and quarantining the contacts of those who are ill - in theory it should be very easy to contain Ebola," says Piot.

In practice though, other factors can make fighting an Ebola outbreak a difficult task. People who become ill and their families may be stigmatised by the community - resulting in a reluctance to come forward for help. Cultural beliefs lead some to think the disease is caused by witchcraft, while others are hostile towards health workers.

"We shouldn't forget that this is a disease of poverty, of dysfunctional health systems - and of distrust," says Piot.

For this reason, information, communication and involvement of community leaders are as important as the classical medical approach, he argues.

Ebola changed Piot's life - following the discovery of the virus, he went on to research the Aids epidemic in Africa and became the founding executive director of the UNAIDS organisation.

"It led me to do things I thought only happened in books. It gave me a mission in life to work on health in developing countries," he says.

"It was not only the discovery of a virus but also of myself."

Peter Piot spoke to World Update on the BBC World Service

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.