Sulphur surplus: Up to our necks in a diabolical element

- Published

Sulphur has many uses, from making acid to stiffening rubber, but right now we have more than we need - a lot more. It's worth hanging on to, though, because one day it may help feed the world.

"A sulphur mine in Sicily is about the nearest thing to a hell that is conceivable in my opinion." So wrote the American author Booker T Washington in 1911, referring to what was at the time the world's main source of this distinctive yellow mineral.

Washington, a former slave, was moved by the plight of the young children forced to work 10-hour shifts underground on the slopes of Mount Etna, carrying heavy loads in unbearable temperatures. But element 16 of the periodic table has a long cultural association with Satan and the underworld.

The most obvious reason for this is its connection with volcanoes and hot springs, where gases - hydrogen sulphide and sulphur dioxide - emerge from the Earth's fiery bowels, and react with one another to form sulphur and water.

But sulphur's association with volcanoes is only one of its demonic properties, as Prof Andrea Sella of University College London demonstrates at a hairdressers' salon in central London.

"This is a dangerous element, which has extraordinary and very evocative smells associated with it," he says, setting fire to a lock of hair. The stench is truly unpleasant. Hair contains sulphur, he explains, as indeed do matchsticks.

While elemental sulphur itself doesn't smell, this odour- of sulphur dioxide - is only one of a panoply of stinks that sulphur compounds can produce.

The presence of hydrogen sulphide yields the distinctive "bad-egg" smell of rotten cabbages, farts, volcanoes - and, of course, bad eggs.

These compounds are often associated with decay, which is perhaps why our noses have evolved to be acutely attuned to them, detecting some at levels as low as a few parts per trillion.

Sulphur is often associated with the smell of rotten eggs

So we have volcanoes and stench. But there's more. Sulphur is a rock that burns - hence its Old English name "brimstone", meaning burning stone. And it melts too, at a mere 115C - just above the boiling point of water - turning an evil-looking dark red colour. But heat it further, and it thickens into a weird toffee-like substance.

What's going on?

Sulphur atoms love to stick to each other. In its familiar yellow solid form, sulphur comprises ring-shaped molecules, each made up of eight atoms. As it melts, those molecular doughnuts crack open, and with greater heat they begin to link up into ever longer chains, giving the molten sulphur its strange plasticity.

By now I hope you agree that sulphur's diabolical reputation is well earned.

But why were people mining it in Sicily a century ago?

It turns out that the readiness of sulphur atoms to link up with each other is very useful. In our bodies, sulphur helps to make hair and nails - long chains of proteins called keratin, which sulphur helps glue together. (When people have their hair curled or straightened, the sulphur atoms are temporarily uncoupled from each other, enabling the hair to be reshaped, before they reset, locking the new shape in place.) And the same gluing and solidifying property is exploited in industry.

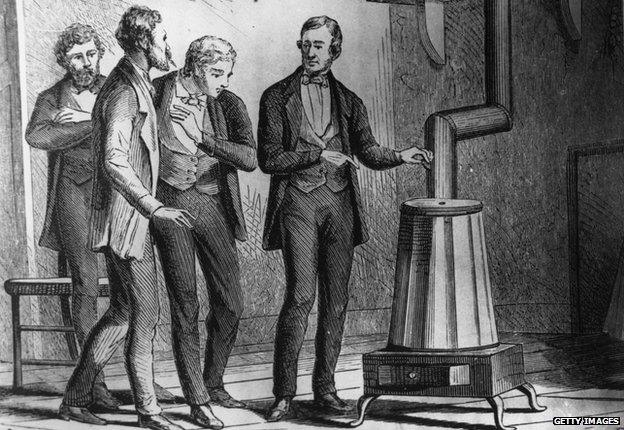

Charles Goodyear, in the 19th Century, found that adding sulphur to latex - the goopy sap of the rubber tree - created a much firmer, more durable material, which he used to produce the first tyres and inner tubes. The process was dubbed "vulcanisation" after Vulcan, the Roman god of fire (and volcanoes), and is still used to make rubber today.

Charles Goodyear demonstrating the Vulcanisation process

Sulphur can also be added to asphalt, to make it more resilient, and more resistant to rutting, and can play a similar role in concrete and the durable plastics used in cars.

But the biggest modern use of sulphur - about 95% by volume - is to make the frighteningly corrosive sulphuric acid, H2SO4.

The first acid works were built as far back as the 18th Century in the pretty English village of Twickenham, of all places. Nearly 300 years later sulphuric acid is the world's biggest industrial chemical by volume. It's used, among other things, to manufacture detergents (sodium sulphates are handily soluble in warm water), and to help process wood cellulose into cellophane and rayon fibre. But its greatest use is in dissolving rocks.

Mining companies pour the acid on to ores in order to extract valuable minerals such as copper, nickel, vanadium, and above all phosphorus. In this fashion, about half of the world's sulphur goes into making the phosphate fertilisers used to boost crop yields and feed the planet.

Dr Robert Ballard discovered that life forms can exist even in total darkness at the bottom of the sea by synthesising the hydrogen sulphide released from vents in ocean floor

Any strong acid will dissolve rocks, but one of sulphuric acid's advantages is that its main constituent is abundant, cheap and surprisingly safe to transport.

Once the acid has done its work, the sulphur ends up in a by-product salt. Much of it finds a use, notably calcium sulphate, or gypsum, which goes into building materials such as plasterboard.

So sulphur, as well as being diabolical, has many uses - which makes the sight greeting motorists on Highway 63, half an hour north of Fort McMurray in the Canadian province of Alberta, rather surprising.

Looming on the horizon appear some enormous and luridly yellow structures, with strangely staggered walls. On closer inspection, they turn out to be not buildings, but humungous blocks of pure sulphur - millions of tons of it. The largest measures 260m by 340m, and is about 20m high - making it approximately the same volume as the Burj Khalifa, the world's tallest skyscraper.

Why is so much of this useful element sitting idle in the wilds of Canada?

Sulphur is still mined from an active volcano in Java

The answer is that we are producing more of it than we can use. Nobody mines sulphur any more (though some Javans do still pick it from an active volcano). Instead we get it as a by-product of the petrochemicals industry.

"Sour" oil, gas and coal contains sulphur. It is called "sour", because when it burns it produces those pungent sulphur dioxide fumes. And they eventually fall back to earth as acid rain.

For those too young to remember, acid rain was - rather like the depletion of the ozone layer - an early environmental crisis, and an early success story. Back in the 1970s it became apparent that these sulphurous plumes were killing trees, dissolving statues and upsetting aquatic eco-systems.

So legislation was passed - including a highly effective pollution permit trading system in the US - that encouraged energy companies to cut back their emissions.

One part of the solution was to stop using the more sulphur-rich fossil fuel sources, which included most of the UK's remaining coal mines. The other part was to extract the sulphur before burning. The sulphur blocks in Alberta come from the Canadian Province's oil-producing tar sands. And they've been accumulating for some years already - the sulphur price has been depressed since the late 1990s.

The quack doctor Joshua Ward

"Joshua Ward was a quack doctor and fraudster. Born in Yorkshire, he came to London and invented a medicine called 'Joshua Ward's drop' that was spuriously supposed to cure people of any illness they had.

"Convicted of fraud, he fled to France, staying there for 15 years before returning to England where he was pardoned by George II.

"He set up his 'great vitriol works' in Twickenham in about 1736. The acid was produced by igniting saltpetre on a large enough scale to allow continuous production. So the price was reduced to about one sixteenth of its former cost.

"It caused a stink - literally a stink. Sulphur makes a very unpleasant smell when it is manufactured, and this permeated the whole neighbourhood.

"The local gentry got so fed up they took an action out in Westminster Hall, so he had to close down the business.

"He was an enormous celebrity, very good at self-publicity. The poet Alexander Pope wrote about him, and he was buried in Westminster Abbey.

"He also had a statue made of himself by Agostino Carlini. It's very good, but was considered too ostentatious to place in the Abbey."

- Anthony Beckles-Willson, trustee of the Twickenham Museum

Mount Etna. "A sulphur mine in Sicily is about the nearest thing to a hell," wrote Booker T Washington

"They can't ship it economically to markets from where they are in northern Alberta," explains Richard Hands, editor of industry tome, Sulphur magazine. "And so it sits there, several million tons, in massive great sulphur blocks."

But it could be that Alberta will soon be joined by other parts of the world. The hydrocarbon industry is rapidly running out of "sweet" low-sulphur oil and gas sources, and so is returning to those previously spurned sour sources, with several projects about to start producing.

"Most of it is coming from the Middle East, particularly Abu Dhabi, also central Asia," says Hands. "We're producing much more sulphur than we can use in the sulphuric acid industry, and over the next few years it is looking like we are going to have a bit of a glut. I imagine we will end up pouring a lot of it to block in the Middle East."

And there it will sit until we need it again - because there is another source of demand for the element which looks set to grow steadily for the foreseeable future, agriculture.

Like the phosphate fertilisers that sulphuric acid helps to produce, the element sulphur is itself a nutrient for plants and animals (0.25% of your body is composed of sulphur, and it's not just in your hair). And the very same environmental restrictions that have created the sulphur glut also mean that farmers now need to buy it.

"Ironically, one of the reasons why we now need to add sulphur to the soil is because, as the legislation has got tighter on air emissions, there is actually less sulphur going into the soil through acid rain," explains Mike Lumley of Shell Sulphur Solutions, a unit of the Anglo-Dutch oil giant.

Today's sulphur glut will not last forever. Eventually either the sour oil and gas will run out, or the world will stop digging the stuff up as it switches over to cleaner (and potentially far cheaper) renewable energy sources.

Meanwhile, with the world's population set to reach 10 billion by mid-century, the need to boost crop yields will intensify - and that means a lot more demand for sulphur, both as a fertiliser itself, and to produce phosphate fertilisers.

So my advice is to hop on a plane to Fort McMurray and enjoy those Canadian wonders while they last.

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.