The tunnels that house Goering's wine collection

- Published

It's not only Ukraine that has been moving towards a closer relationship with the European Union. Moldova too has reached out to Brussels but Russia has responded by targeting its vineyards, which have an intriguing past.

Moldova feels like the corner of Europe that time forgot. Beyond the capital Chisinau the countryside has barely changed in 100 years. The roads are a bone-shaking ordeal. Horses haul carts loaded with produce and people. Geese glare at outsiders. And while the horrors of an ugly conflict have focused world attention on neighbouring Ukraine, Moldova's rural population has more parochial concerns like bringing in the harvest.

I join Vassily Kulyev on his rusting Soviet-era harvester as it wheezes and groans through a field of barley. Two other men as well worn as the machine itself are perched on top of the grain tank. Vassily tells me each member of the crew will get £3 ($5) for working from dawn till dusk. I ask him where the young men are. "Gone abroad," he says flatly.

Moldova's rural economy is built on small farms, hard labour and low returns. Ever since the collapse of the USSR and Moldova's transformation from Soviet Republic to independent nation, it has been the poorest country in Europe.

But there is one fruit of the Moldovan soil that holds out the prospect of something better - the grape. Across much of the country vines stretch out to the shimmering horizon.

Remarkably, this neglected nation of fewer than four million souls has consistently been among the world's top 10 wine exporters. Moldova's wine producers prop up the national economy. At least they did, but in the past year their sales have slumped, their mood has soured and the reason lies not in the weather, nor the soil, but in Moscow.

Russians have long had a liking for Moldovan wine. From the Tsars to the Soviet commissars, Moscow treasured its claim on the country's vineyards. And nowhere is that more obvious than the Cricova Estate. The winery boasts thousands of hectares of beautifully tended vines, but the real splendour of Cricova lies underground.

Half a century ago the Soviet masters of Moldova built one of the world's greatest wine stores in a warren of old mining tunnels deep inside the limestone hills - 70 miles (113km) of subterranean chambers housing more than a million bottles.

Cricova's marketing director Alexandru Alexeev gives me a guided tour. He stops his golf buggy beside an alcove filled with dusty bottles. "This is Herman Goering's private collection, taken by the Red Army from Berlin in 1945," he says.

I grab a bottle of the Mosel white, rub off the dust and hold it to the light wondering if this had been touched by Hitler's henchman. It's murky, bits of cork appear to be floating in the liquid.

"Don't remove the dirt, even the dust is valuable," Alexeev admonishes. "How valuable?" I ask. "Well, each bottle is worth £15,000 and there are 129 of them," he says.

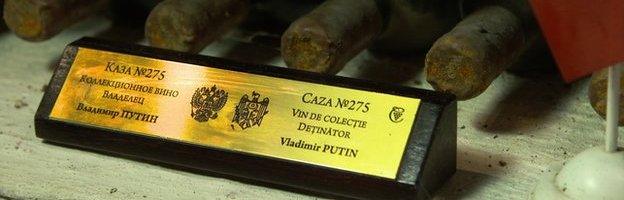

But it's not Herman Goering's wine that is on Alexeev's mind today, it's the collection belonging to a contemporary figure - a certain Vladimir Putin. Mr Putin has his own cave in the Cricova tunnels. Every statesman who visits the winery is accorded the honour of a personal collection, but Mr Putin's stash is noticeably bigger.

"He has been here several times - he likes this place so much he held his 50th birthday party here," Alexeev tells me. Then his face darkens. "Of course things have changed a lot since then."

Russia's love affair with Moldovan wine, fostered during the Soviet supremacy, has come to a bitter end. Mr Putin has been infuriated by the Chisinau government's decision to cosy up to the EU. And as Moldovans know from events in neighbouring Ukraine, Moscow is inclined to exact retribution. To punish the Moldovans for shunning his plan for a "Eurasian Union" spanning the former Soviet empire, Mr Putin ordered a ban on the importation of Moldovan wine.

"It has been like a cold shower on us - we've lost 30% of our exports but we have to learn from this. We need to find new markets in Europe, in the US and in China. We cannot rely on Russia," says Alexeev.

So now Moldova's pro-European government is watching the horrors in Ukraine with a deep sense of foreboding. When Mr Putin talks of restoring Russian greatness, of reasserting Moscow's legitimate interests, he's sending a message to Chishinau as well as Kiev.

As the winemakers of Cricova know to their cost, Russia still has leverage in the lands it once ruled. The wine embargo was the opening salvo, but it may not be where the hostilities end.

How to listen to From Our Own Correspondent, external:

BBC Radio 4: Saturdays at 11:30

Listen online or download the podcast.

BBC World Service: Short editions Monday-Friday - see World Service programme schedule.

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.