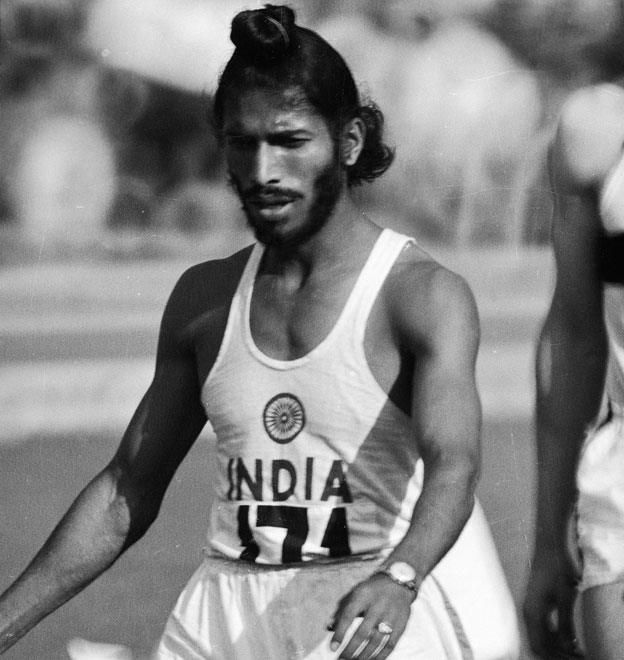

The 'Flying Sikh' who won India's first Commonwealth gold

- Published

When Milkha Singh took to the track at the 1958 Commonwealth Games in Cardiff most people had never heard of him. But he was to make history there and is now hailed as one of India's greatest athletes.

It was the night before the 440 yards final at the British Empire and Commonwealth games in Cardiff and Milkha Singh was having trouble sleeping.

"When a person makes it to the final he is under so much stress that he is unable to sleep," recalls Singh. "It was a very difficult night."

Singh had won two gold medals at the Asian Games in Tokyo just a month before, but the Commonwealth Games were different.

"No-one had heard of Milkha Singh at the Commonwealth Games," he says. "There were competitors from Australia, England and Canada, from Uganda, Kenya and Jamaica - the athletes who took part were world class."

He also had the hopes of the Commonwealth's most populous nation weighing heavy on his shoulders. India had never won a gold medal in the history of the games.

Singh grew up in a small village in what, during his childhood, was still British India. He would walk 10km barefoot to school every day, crossing burning sands, and wading through two canals, his books balanced on his head.

He was a teenager in 1947, when partition created the two sovereign nations of India and Pakistan. Punjab, where Singh lived, was divided between the two countries and some found themselves on the wrong side of this new border.

Many Sikhs and Hindus faced persecution in Pakistan as did many Muslims in India. About half a million people were killed and millions more displaced.

As Sikhs in Pakistan, Singh's family did not escape the violence.

Terrible images of dogs and vultures scavenging on mutilated bodies still haunt Singh's memories of that time. He remembers people were so fearful that they killed their young daughters rather than risk them being kidnapped.

"My village was surrounded," he recalls. "We were told to convert to Islam or prepare to die."

When their village was attacked - by outsiders, he emphasises, not by Muslim neighbours - Singh witnessed the murder of his parents and some of his brothers and sisters.

He escaped to the jungle with a group of other boys, then managed to get on a train bound for Delhi.

The trains were being searched by vigilante groups, but the boys hid under the seats in the ladies' carriage and begged the women not to turn them in. They didn't and the boys survived.

After several difficult years living in Delhi, Singh joined the Indian Army - and it was here that his athletic prowess emerged. His instructor in the army taught him how to run properly and after coming sixth in a cross-country race against 400 other soldiers, he was selected for further training.

"All of this started when I was with the army," he says. "I give credit to them for making me a world famous name."

In 1958, on the day of the big race in Cardiff, the athletes were taking their place on the starting line. Singh knew that the man to beat was South Africa's Malcolm Spence.

"My coach convinced me - drilled it into my head - that I could win the race regardless of whether Spence was a world class, world record holder. He was nothing before me if I ran my race as planned."

copy.jpg)

Singh in army uniform with India's then Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru

The stadium was full but Singh remembers there were just two or three Indians among the spectators - one of those watching was Vijay Lakshmi, the sister of the then Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru.

"I said my prayers, I touched my forehead to the ground and said to God, 'I am going to try my best but India's honour is in your hands,'" Singh says.

The runners took their marks and the race began. Just as his coach instructed, Singh ran the first 350 yards of the race as fast as he could - he delved deep into his reserves and took the lead but Spence followed close behind him.

"While I was running, I stole a glance sideways and saw Spence just behind my shoulder. He almost reached me but couldn't edge past. I won the race by a margin of just half-a-foot."

The stadium erupted as Singh crossed the finish line. "Everyone was shocked at how this boy from rural India, who used to run barefoot and who had never received any training, had won gold in the Commonwealth Games," he says.

Singh had tears in his eyes as he took his place on the medal podium. India's tricolour was hoisted up the flag pole and the anthem rang out around the stadium. "I was crying with joy and thinking to myself, 'Milkha Singh, today you have truly done India proud.'"

After the race, Nehru's sister came to congratulate him and said that her brother, the Prime Minister, wanted to know what he would like as a reward.

"Back in those days we were too simple to know what to ask for and how. I could have asked for 200 acres in Punjab or two to three bungalows in Delhi. But in those times I was very embarrassed to ask for anything. All I asked was that the Prime Minister declare a day's holiday in India - and he did."

Singh returned home to a hero's welcome. Military bands greeted the entire Indian team at the airport and they were invited to meet Prime Minister Nehru. "Our reception was overwhelming. The Indian team was given a lot of respect everywhere," he says.

Singh continued to run for his country - he came fourth in the 1960 Olympic Games in Rome, just beaten to the bronze medal by Spence, his main rival from Cardiff.

That same year, he was invited to take part in the 200m event at an International Athletic competition in Lahore, Pakistan. He hadn't been back to Pakistan since fleeing in 1947 and initially refused to go.

"How can a boy, who has seen his parents murdered before his eyes one night, their throats slashed in front of him, his brothers and sisters hacked to death, ever forget those images?" he says.

But hearing that Singh wasn't going to go to Pakistan, Nehru asked to see him and convinced him to change his mind. "He said to me, 'They are our neighbours. We have to maintain our friendship and love with them. Sport fosters these things, therefore you should go.'"

Singh did go to Pakistan and recalls that when he crossed the border he saw children lining the road holding the flags of India and Pakistan - the welcome was "overwhelming".

.jpg)

Milkha Singh attends the the launch of the film Bhaag Milkha Bhaag in 2013

His main rival in the event was Pakistan's Abdul Khaliq. Newspapers and banners along the street in Lahore were describing it not only as a clash between these two athletes but as "a clash between Pakistan and India".

Despite the huge support for Khaliq in the stadium, Singh went on to win that race while Khaliq took the bronze medal. As Gen Ayub Khan, Pakistan's second president, awarded the competitors their medals, Singh received the nickname that would stick with him for the rest of his life.

"Gen Ayub said to me, 'Milkha, you came to Pakistan and did not run. You actually flew in Pakistan. Pakistan bestows upon you the title of the Flying Sikh.' If Milkha Singh is known as the Flying Sikh in the whole world today, the credit goes to General Ayub and to Pakistan," Singh says.

Now, nearly 55 years on, with more than 77 international race wins to his name and a successful Bollywood film made of his life story, the Flying Sikh still has one outstanding ambition. He wants to live to see an Indian win Olympic gold in a track and field event, adding to the country's current haul of gold medals in hockey and shooting.

"My greatest desire before I die is to see an Indian win the gold medal that I lost in the Olympics," he says.

"My last wish before leaving this world is to see an Indian athlete, male or female, shine and give me the opportunity to see India's tricolour hoisted in the Olympic arena and hear the national anthem played there. This is my last wish."

Milkha Singh spoke to Sporting Witness on the BBC World Service

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.