America's 'inexorably' botched executions

- Published

If there seem to have been a lot of botched executions in the US recently, there have. It turns out that lethal injection - by far the most common method of execution in those states that still practise capital punishment - is also the most likely to go wrong.

Botched executions have been an "inexorable part" of the story of capital punishment in America, according to Prof Austin Sarat of Amherst College.

"If you look over the course of the 20th Century, about 3% of all American executions were botched," says Sarat, who studied all of the nearly 9,000 US executions from 1890 to 2010 for his book Gruesome Spectacles: Botched Executions and America's Death Penalty.

The rate of botched lethal injections, however, was a lot higher, at 7.1%.

By "botched", Sarat means the executioners departed from official legal protocol or standard operating procedure - which can result in a prolonged or painful death.

These botched executions have played a big role in fuelling public revulsion, which has driven many of the changes in US execution methodology over the years, and contributed to the abolition of the practice in 18 states.

"Part of the reason we have lethal injection is because of the botched electrocutions that were occurring in the 1970s," Sarat says. "And part of the reason we had electrocutions is because in… the early 20th Century, people found hanging to be gruesome."

Gas chambers, meanwhile, were widely considered unacceptable after the Holocaust, though three states still allow condemned men and women to choose this form of death.

But all of these systems, according to Sarat's data, had a lower botch-rate than lethal injection.

The point of lethal injection, when it was introduced in the late 1970s, was to look "clean and sterile and pretty", an anaesthesiologist, who asked to remain anonymous, told the BBC.

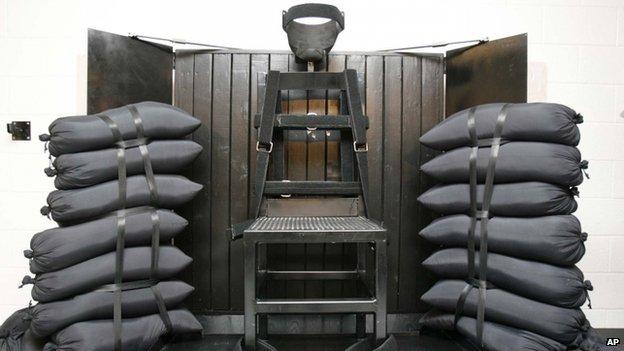

Firing squad execution chambers can still be found, including one in Utah State Prison

Originally proposed by an Oklahoma coroner, the conventional system consists of three drugs - an anaesthetic to relieve consciousness and pain, a paralytic to prevent movement, and a drug to stop the heart, causing death. But it does not always go smoothly. It was after Oklahoma inmate Clayton Lockett took 40 minutes to die in May that President Barack Obama directed the attorney general to review how the death penalty is applied.

Some of the botched cases have arisen from problems with dosing, the difficulty executioners experience getting hold of good quality drugs, and the varying level of training given those administering the fatal injection. Doctors run the risk of losing their medical licence if they take part.

US execution by numbers

Currently, 35 US states use lethal injection as the primary method of execution - this includes three states which have stopped handing down the death penalty but still have prisoners on death row

In some states a person sentenced to death may choose an alternative form of execution

Eight US states allow electrocution, three allow the gas chamber, another three allow hanging, two allow the firing squad

The last time an inmate was executed by a means other than lethal injection was in January 2013, when a 42-year-old man was electrocuted in Virginia

Source: The Death Penalty Information Center

"The enterprise is flawed. Using drugs meant for individuals with medical needs to carry out executions is a misguided effort to mask the brutality of executions by making them look serene and peaceful," US Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals Chief Judge Alex Kozinski wrote on 21 July, external.

He advocated a return to the firing squad - used only 34 times in the period studied by Sarat, but never botched according to his data.

But University of California, Berkeley law professor Franklin Zimring takes a different view.

"It's rather a fantasy to think that some of the tried and true methods, like a firing squad, are going to make things different or better," he says.

"Anything you use to put people to death in a relatively public way is going to look pretty problematic."

Sarat argues there will always be mistakes.

"The question is, 'What is the tolerance of people for error?'" he says. "There is no technology over the horizon and no technology exists that will be foolproof."