Can you die from a broken heart?

- Published

The poignancy is enough to make anyone weep. Just a day after a beloved daughter dies, the mother passes away. It is a tragedy with a hint of sweetness - the two who lived each other's lives, end those lives together.

And it is not uncommon. We do not know the cause of Debbie Reynolds' death but there are more instances of two people who love each other dying in short proximity than you might think. There are medical reasons why it is possible to die of a broken heart.

I once went to the joint funeral in Wales of a couple who died within a week of each other. Then I read a report in the news about a man in California who died hours after his wife. It made me wonder how often this happens - and what could be the reason.

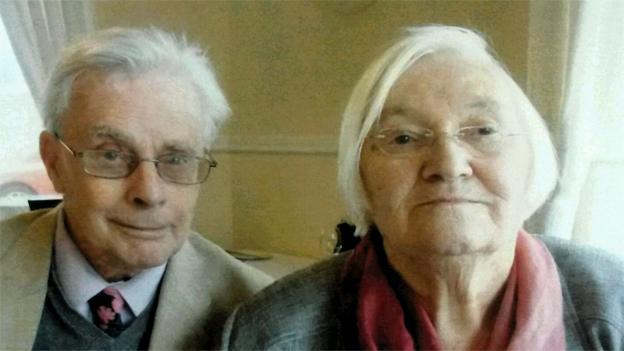

In the first case, the widower selected a poem to be read at his wife's funeral - it talked of "two lovers entwined" and a journey "to the end of time's end". But before that funeral took place, the husband, Edmund Williams, also died. He and his wife, Margaret, had been married for 60 years and their love had endured. In their late 80s, they would still go into their garden holding hands. Parting broke his heart.

Edmund and Margaret Williams died a week apart, after 60 years of marriage

And about the same time Don and Maxine Simpson died in Bakersfield in California. He was 90 and she was 87, and they were as inseparable as they had always been after meeting at a bowling alley in 1952 and marrying that same year. Maxine died first and four hours later, by her side, Don followed.

It looks like a pattern, and perhaps it is.

Research published two years ago in the journal JAMA Internal Medicine, external found that, while it happened rarely, the number of people who had a heart attack or a stroke in the month after a loved-one died was double that of a matched control group who were not grieving (50 out of 30,447 in the bereaved group, or 0.16%, compared with 67 out of 83,588 in the non-bereaved group, or 0.08%).

One of the authors, Dr Sunil Shah of St George's at the University of London, told the BBC: "We often use the term a 'broken heart' to signify the pain of losing a loved-one and our study shows that bereavement can have a direct effect on the health of the heart."

Coloured chest x-ray of patient suffering from cardiomyopathy

Some people talk about "broken heart syndrome", known more formally as stress cardiomyopathy or takotsubo cardiomyopathy. According to the British Heart Foundation, external, it is a "temporary condition where your heart muscle becomes suddenly weakened or stunned. The left ventricle, one of the heart's chambers, changes shape."

It can be brought on by a shock. "About three quarters of people diagnosed with takotsubo cardiomyopathy have experienced significant emotional or physical stress prior to becoming unwell," the charity says. This stress might be bereavement but it could be a shock of another kind.

There are documented cases of people suffering the condition after being frightened by colleagues pulling a prank, or suffering the stress of speaking to a large group of people. It's speculated that the sudden release of hormones - in particular, adrenaline - causes the stunning of the heart muscle.

This is different from a heart attack, which is a stopping of the heart because the blood supply is constricted, perhaps by clogged arteries.

"Most heart attacks occur due to blockages and blood clots forming in the coronary arteries, the arteries that supply the heart with blood," says an FAQ on broken heart syndrome, external published by Johns Hopkins University.

What becomes of the broken-hearted

"Broken heart" is referred to in the 1611 King James Version of the Bible: "The Lord is nigh unto them that are of a broken heart; and saveth such as be of a contrite spirit." (Psalms 34:18)

Shakespeare features several characters who expire for love - King Lear perishes shortly after discovering the murder of his daughter Cordelia, and in Romeo and Juliet, Lady Montague is reported by her husband to have died of a broken heart: "Grief of my son's exile hath stopp'd her breath"

Alfred Lord Tennyson's 1842 poem, The Lady of Shalott, relates how the tragic damsel of Arthurian legend lay down in a boat to die and be discovered by Lancelot, the knight she loved: "For ere she reach'd upon the tide/ The first house by the water-side,/ Singing in her song she died,/ The Lady of Shalott."

By contrast, most patients who suffer from cardiomyopathy "have fairly normal coronary arteries and do not have severe blockages or clots", the website says.

Many people simply recover - the stress goes away and the heart returns to its normal shape. But in some, like the old or those with a heart condition, the change in the shape of the heart can prompt a fatal heart attack.

The scientific name, takotsubo cardiomyopathy comes from the Japanese word for a type of round-bottomed, narrow-necked vessel, external used for catching octopuses. The sudden stress causes the left ventricle of the heart - the one that does the pumping - to balloon out into the shape of the pot.

"What will survive of us is love," wrote Philip Larkin, referring to the Arundel tomb in Chichester Cathedral

There is also evidence of an increased risk of death after the hospitalisation of a partner, according to a study published in 2006 in the New England Journal of Medicine. Other research published in 2011, meanwhile, suggests that the odds of the surviving partner dying are increased for six months, external after their partner's death.

The researchers pointed out that a mutually supportive marriage acts as a buffer against stress. Partners also monitor each other and encourage healthy behaviour - reminding each other to take their daily tablets, for example, and checking they don't drink too much.

Whatever the science behind "broken heart syndrome", the results are bitter-sweet. There is, of course, the grief of a bereaved family who have lost two people they love. But there is also often a relief that a couple deeply in love should have exited life together.

Edmund Williams' poem for his wife Margaret talked about "two lovers entwined" and a journey "to the end of time's end".

If there is a benevolent heart condition, surely takotsubo cardiomyopathy is the one - but "dying of a broken heart" puts it better.

An earlier version of this feature appeared in August 2014.

Additional reporting by Tammy Thueringer.

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.