Silent Darien: The gap in the world's longest road

- Published

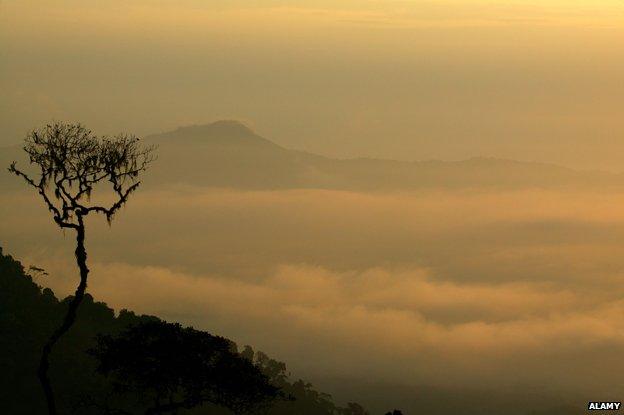

Stretching from Alaska to the pencil tip of Argentina, the 48,000km-long Pan-American Highway holds the record for the world's longest motorable road. But there is a gap - an expanse of wild tropical forest - that has defeated travellers for centuries.

Explorers have always been drawn to the Darien Gap, but the results have mostly been disastrous. The Spanish made their first settlement in the mainland Americas right here in 1510, only to have it torched by indigenous tribes 14 years later - and in many ways the area remains as wild today as it was during the days of the conquest.

"If history had followed its usual course, the Darien should be today one of the most populated regions in the Americas, but it isn't," says Rick Morales, a Panamian and owner of Jungle Treks, one of a few adventure tour companies operating in the region.

"That's remarkable if you consider that we live in the 21st Century, in a country that embraces technology and is notorious for connecting oceans, cultures, and world commerce."

The gap stretches from the north to the south coast of Panama - from the Atlantic to the Pacific. It's between 100km and 160km (60-100 miles) long, and there is no way round, except by sea.

Yaviza, Panama (above) is at one end of the gap... the other is at Turbo, Colombia

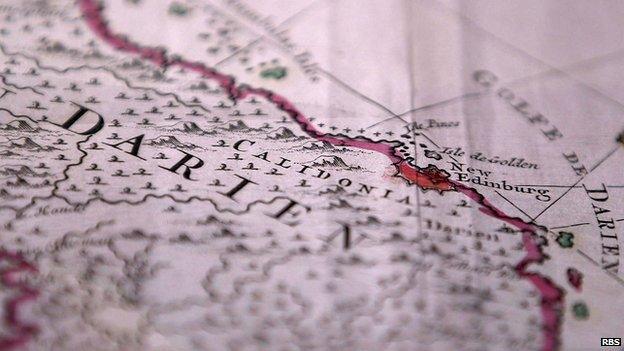

After the conquistadors, the Scots also wagered badly here. Having established a coastal trading colony in 1698, most settlers perished from disease and Spanish attacks. The loss would deplete enough Scottish wealth to compromise their independence less than a decade later, when the country opted to sign the Treaty of Union.

It was only in 1960 that anyone managed to cross the Darien Gap by car - in a Land Rover dubbed The Affectionate Cockroach and a Jeep. It took nearly five months, averaging just 200m per hour.

The team included noted Panamanian anthropologist Reina Torres de Arauz and her cartographer husband, Amado Arauz. Hand-chopping a route through the jungle, they forded hundreds of rivers and streams, improvising bridges from palm trunks that didn't always hold up. Their research later helped establish the Darien National Park, a Unesco World Heritage Site.

Twelve years later, the renowned explorer, Col John Blashford-Snell, led a 60-person crew in Range Rovers on the first complete road trip from Alaska to Cape Horn, via the Darien Gap. This short section of the route, he describes as the toughest challenge of his career.

John Blashford-Snell's 1972 trans-Darien expedition

The seasonal rains came early and locked the vehicles in mud. "Something had to go and it was the back axles," Blashford-Snell recounts. "They exploded like shells with shrapnel coming through the floor."

Redesigned car parts were parachuted in a month later. Later, custom-built inflatable rafts floated the vehicles across the problem area of the vast Atrato swamp. Eventually, they made it, though half the team had succumbed to trench foot, fevers and other ailments.

More from the Magazine

The story of the ill-fated Scots colony at Darien survives in the oral history of the Kuna Indians, who are the only people who have ever settled successfully in this inhospitable place.

In 1698, a fleet of five ships sailed from Leith docks near Edinburgh carrying 1,200 settlers to found a colony in Panama. Few of the Scots who went, made it home.

Alan Little on the colony which brought down Scotland (May 2014)

Half a century on, the number of successful motorised crossings can be counted on two hands. These days armed drug runners are as big a hazard as the region's lethal pit vipers.

Those who wish to enter the interior must register in advance with Senafront (Servicio Nacional de Fronteras), Panama's border police, who control access with multiple checkpoints along the Pan-American Highway. At these stops, documents are checked and rechecked. At any point a traveller may be turned back.

At the run-down frontier town of Yaviza, the road ends but settlements do not. Rivers are the highways of the interior, with small motor boats and dugout canoes providing expensive and infrequent passage, which must often be timed to coincide with ocean tides. The destination, for those intending to continue south by road, is the town of Turbo in Colombia.

Missionaries have disappeared in the interior, and others, including orchid hunters Tom Hart Dyke and Paul Winder, have been kidnapped. Yet travelling into the interior is still worth the effort for conservationists, for whom the Darien is a key site, with some of the world's greatest genetic diversity.

With eight other colleagues and students, Dr Ruediger Krahe of McGill University in Canada recently headed to Pena Bijagual, to study weakly electrical fish - fish that use electrical signals for navigation and communication. The village of thatched huts, a 45-minute trip via motor canoe from Yaviza, was the perfect research base. Their Embera hosts offered security and even served them a culinary speciality the researchers had thus far only studied - the macana, a one-metre-long electric fish.

An Embera man traverses the Mogue river in a traditional boat

"We felt super safe there," says Krahe. "It was an amazing place… our very best field site."

But this year, there was no village to go back to. In March, a group of armed outsiders invaded Pena Bijagual. Senafront then engaged in a shootout which killed one assailant and injured policemen. Five months later, the dispersed villagers have still not returned.

The problem with drug-trafficking has increased as maritime patrols have been stepped up, and the trade has been pushed inland. Commissioner General Frank Abrego, director of Senafront, says the traffickers emerged from the remnants of Colombian drug cartels and demobilised guerrilla groups.

They employ local people, mostly indigenous, as porters or guides - to the distress of Tino Quintana, regional cacique or chief of the Comarca Embera, a semi-autonomous indigenous territory. Part of the issue, he says, is isolation which reduces work opportunities and commerce. "So come the narcotraffickers," he says. "They offer considerable sums to our youth to work."

The Lemur Leaf frog is one of the amphibians under threat as a lethal fungus sweeps through Panama

Every so often, the dream of completing the Pan-American Highway is resurrected. The last push came a decade ago from former Colombian president Alvaro Uribe, who anticipated a boom in commerce as the conflict between the government and guerrillas waned. It's bandits who benefit from keeping the Gap a no-go area.

But Panama, along with the US and local indigenous populations, have a range of objections. A road would pose a threat to indigenous cultures, accelerate deforestation and allow the spread of disease - such as foot and mouth cattle disease, which the Gap has so far effectively prevented from spreading to North America.

Rainforest destruction is already evident en route to Yaviza. In April the sale of rosewood or cocobolo was suspended in Panama after it was found that much of it was flowing from illegal sources, and largely from the Darien. The rare hardwood has been valued at $2,000 per cubic metre.

"The worst thing that could happen to the Darien would be the completion of the highway across the Darien Gap," says Michael J Ryan, a University of Texas biologist who researches the amphibians threatened by chytrid fungus in the Darien National Park.

"The loggers will follow the road, forests will fall, and huge chunks of paradise will be lost forever."

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.