The prisoners of Ruhleben

- Published

A recent Magazine article looked at a World War One internment camp in Germany, in which the civilian inmates created a miniature version of Britain, complete with roads named after London streets, a horticultural association and a cricket club.

Unlike a prisoner of war camp, the 5,000 captives at Ruhleben, near Berlin, were not made to work and the German guards at the camp just patrolled the perimeter.

The article about Ruhleben prompted a number of readers to get in touch with pictures, letters and stories of family members who had passed through the camp.

Here are the stories of seven prisoners of Ruhleben.

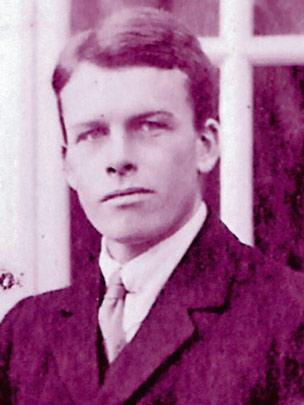

Arthur Smyth

Arthur Smyth

My grandfather, Arthur Smyth, was at Ruhleben. He had been studying medicine at Heidelberg at the outbreak of the war and apparently continued his studies at the camp. He said it offered the best education in Europe because there were so many eminent foreign academics interned at the same time. He made little carvings in his spare time, learned to skate in the winter and played a violin, which we still have (he is pictured at the top of this story amongst a Ruhleben orchestra, third from left on the second row from the back). He did lots of things, but I think he had mixed feelings about it - it was like being at a boarding school and then being made to stay the summer as well.

After the war, he went on to become senior registrar at Addenbrookes hospital in Cambridge, but died from cancer while he was still in his 40s, shortly after World War Two. In March I was in Germany and went and had a look at Ruhleben, but apart from a new sports stadium there was nothing much to see, and I couldn't find a memorial.

Rachael Stainer-Hutchins, Stroud, UK

Two carvings made by Arthur Smyth at Ruhleben

James Chadwick

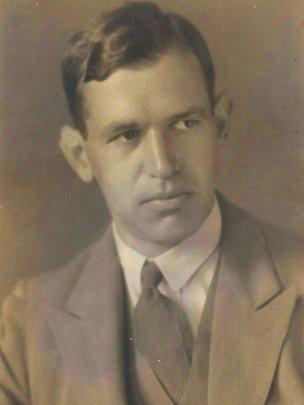

Chadwick in the 1920s

In your article you missed out Ruhleben's most famous inmate - James Chadwick, who later received the 1935 Nobel Prize for Physics, after discovering the neutron. This discovery led directly to the development of the Atom Bomb which ended WW2.

He was in Germany working with Hans Geiger as a young student and was interned at Ruhleben for the duration of WWI.

He had a miserable time, in cramped and cold accommodation, but astonishingly he converted part of his space in the overcrowded loft into a physics lab and performed experiments on ionisation. He improvised a Bunsen burner using melted butter and persuaded his fellow prisoners to operate bellows.

Apparently his captors were quite co-operative and supplied him with scientific equipment.

Luke Davies

William Hohenrein

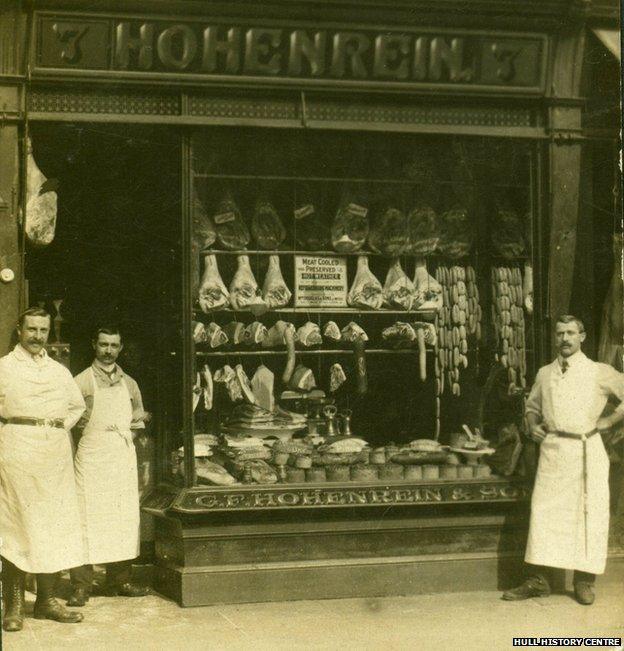

Charles Henry Hohenrein (far left) and George William Hohenrein (far right)

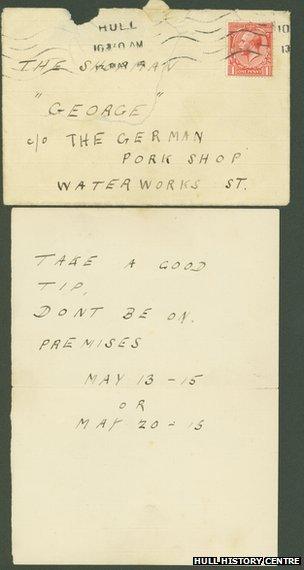

One of the threats sent to Charles Hohenrein

There is a great story, connected with Ruhleben, that highlights how civilians were affected in WWI. I am a local historian from Hull, and I have carried out quite a bit of research on the Ruhleben camp as two brothers from Hull were affected by it. They were the Hohenrein brothers, born in England to German parents. The older brother, George William Hohenrein (but always called William), was in Germany at the outbreak of WWI and was classed as a British citizen, so was interned in Ruhleben with his teenage son, also called William. Both of them wrote letters from Ruhleben to their Hull relatives and these are in the collections of the Hull History Centre. I have read them and they are very moving at times.

Meanwhile, William's younger brother Charles ran two pork butcher's shops in Hull during the war. The shops were repeatedly threatened because although he was a British citizen, he was seen as German. Some of the anonymous letters that he received were almost apologetic in tone. Charles changed the family name to Ross, and closed the shops, but opened one of them again towards the end of the war when the public's attitude began to change.

After the war the Hohenrein family did well on both sides of the North Sea, with Charles Ross getting into the cinema business in Hull, building the Regal, Rex and Regis. But sadly the family was to suffer again due to their location. William's son was working as a doctor in Germany during WW2 and died in an allied bombing raid, while in Hull the butcher's shop was badly damaged by German bombing.

David Smith, Shefford, Bedfordshire

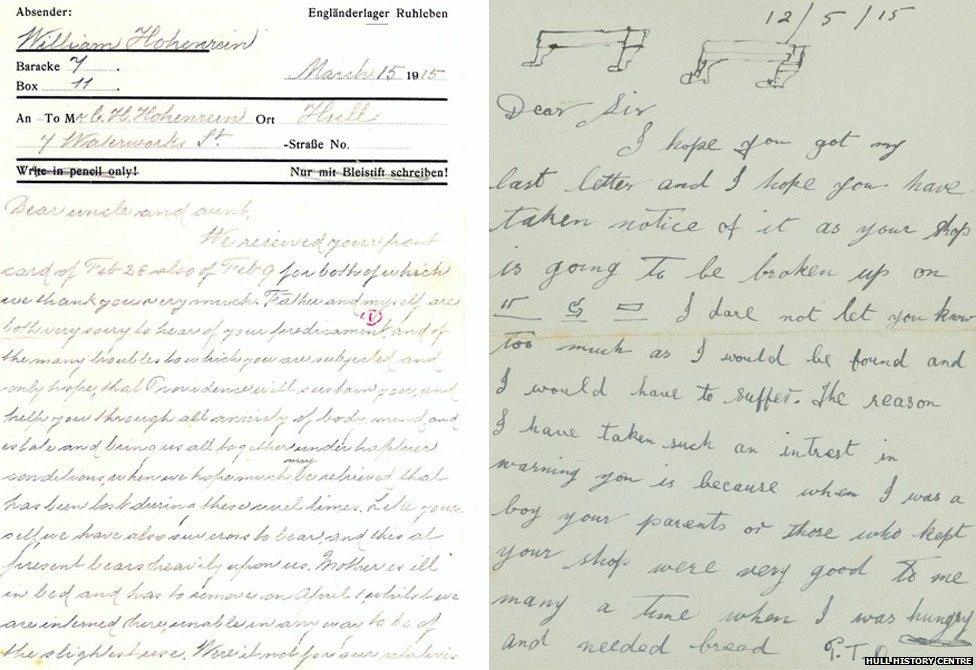

On the left, a letter from William Hohenrein Jr, written from Ruhleben in March 1915. He writes: "Father and myself are both very sorry to hear of your predicament, and the many troubles to which you are subjected… Like yourself we have also our own cross to bear and this at present bears heavily upon us." On the right, another warning letter sent to the shop in May 1915. The writer says: "The reason I have taken such an interest in warning you is because when I was a boy your parents... were very good to me." He goes on to explain the attack will be a revenge for the sinking of the Lusitania that month.

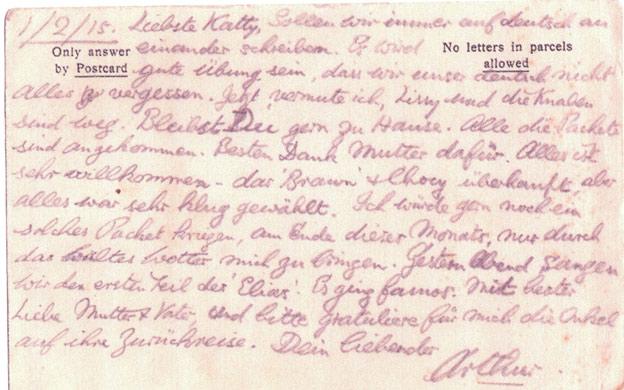

Arthur Gordon Ponsonby

Arthur Gordon Ponsonby in 1919 or 1920

My dad, Arthur G Ponsonby, was at Ruhleben. He graduated from Trinity College Cambridge in the summer of 1914 and was on holiday in Germany visiting relatives when he was taken to the camp. At Ruhleben he worked in the library and devoted himself to learning languages, which equipped him for a subsequent career in the Consular Service.

He didn't harbour any lasting hostility to Germans at all. For some reason he never really talked about the camp, but he used to go to Ruhleben reunion dinners every year.

And he did tell one funny story. Somebody at the camp wrote a postcard home saying "They are keeping our noses to the grindstone," and the German censor took exception to this, saying "We're not such monsters!" The idiom was lost on him.

Dr John Ponsonby, Wilmslow, UK

Written in excellent German, Arthur's postcard from Ruhleben to his sister thanks his mother for a recent parcel, although it says the chocolate and brawn was "a bit over the top". It goes on to request another parcel for the end of the month "in order to get me through the cold weather".

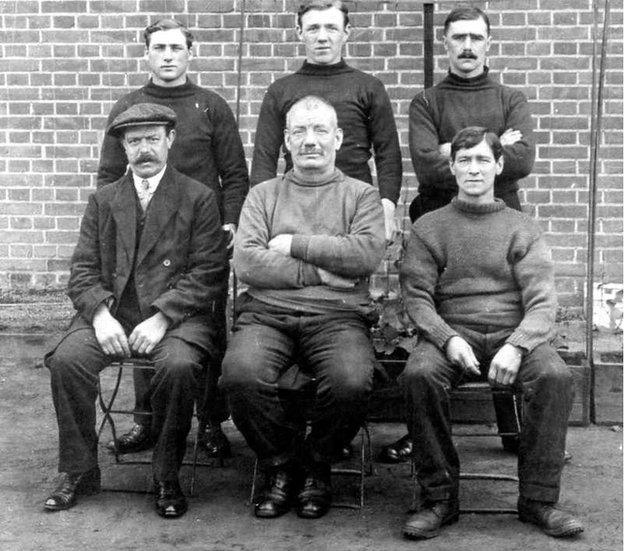

John William Green

Taken at Ruhleben, John Green is seated centre - he had reddish hair, was 6'4" and took size 14 shoes

My great-granddad, who was known as Jack, was the skipper of a steam trawler. He was taken prisoner in the first month of WW1, on 25 August, with his 17-year-old son (my great uncle) and other members of the crew. He recorded a lengthy account of his capture, which begins like this:

"On the 20th August, 1914, we sailed from Grimsby on a fishing voyage, which in ordinary circumstances would have taken eight or nine days, but with fate or the Huns, or both against us, this voyage turned out to be a much longer one, as we did not see Grimsby again until the 28th November, 1918."

His account focuses on the terrible conditions of the prison hulks where he began his incarceration, and the poor treatment of prisoners there.

World War One Centenary

"I have seen the Germans rush in among a crowd of Poles or Coloured men, lashing out right and left for the most trivial offences, and woe betide the poor fellow who was singled out for punishment. He was dragged to some place or other under the bridge, and the groans we heard were terrible, and gave us some idea of what he was going through. He would then be given two or three days in cells and a bread and water diet. The things we heard and saw on board these Hulks made the blood swell in our veins, almost to bursting point - and this was the nation who were going to rule the world."

After some time, they were transferred to Ruhleben, and we know much less about how he and his men got on there. The family back home certainly suffered while he was away, but we've always looked at it fairly positively - that he wasn't sent to France into the trenches.

Margaret Burgess, Holmfirth, UK

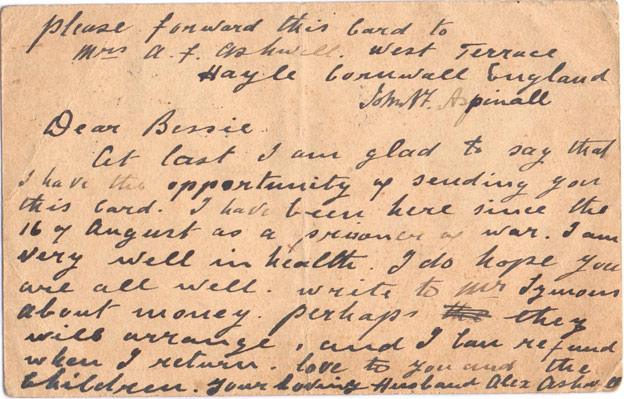

Alexander Ashwell

Alexander Ashwell is on the right in this picture which may well be from the camp

My grandfather, A F Ashwell, was interned for four years until exchanged. He travelled a great deal, managing and installing biscuit factories. He was living in Munchen-Gladbach and the family was about to join him when war broke out. Apparently he was on a boat that had set sail from Germany but was then forced to turn back. My Uncle Arthur always said he should have tried to slip across the Dutch border. Life was very hard for my grandmother and her five children stranded in Cornwall. All their possessions were lost in Munchen-Gladbach.

After the war, my grandfather's wanderlust continued. He went to Japan with his son Frederick and was there during the 1923 earthquake. He earned a fortune but unfortunately for the family spent it all.

My grandfather was opposed to the armistice. He said that granting the Germans an armistice then would lead to another war in twenty years. He did not live to see his prediction come true!

Peter James, Pwllheli, Wales

The postcard that informed Alexander's wife Bessie that he had been taken prisoner

Harry Carter Walsh

Henry Walsh is pictured bottom right with his barrack companions

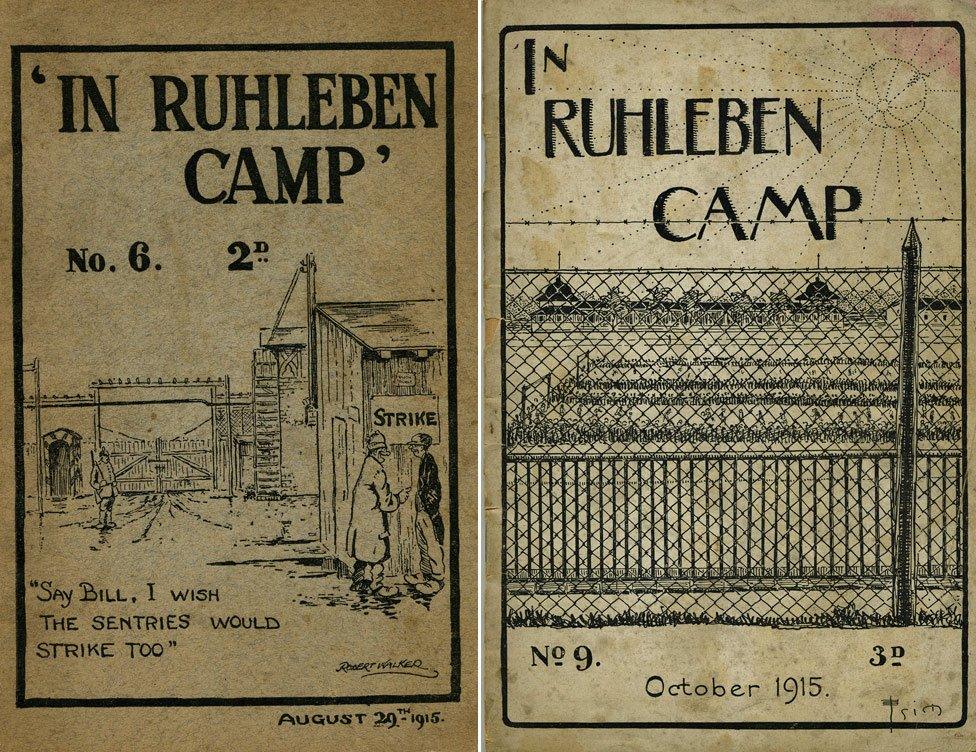

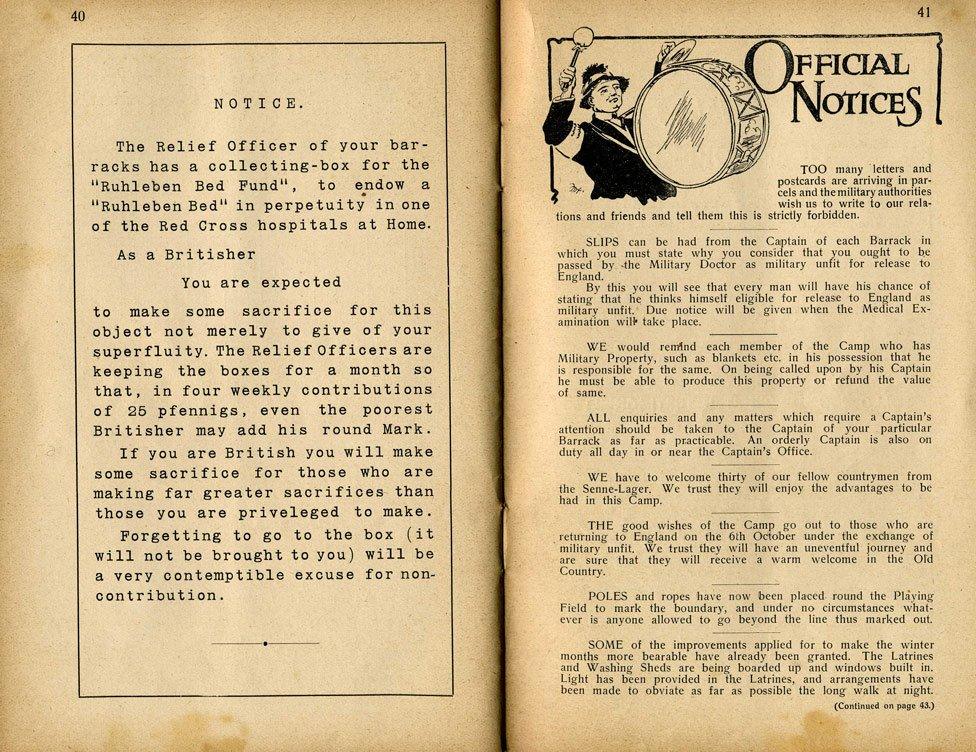

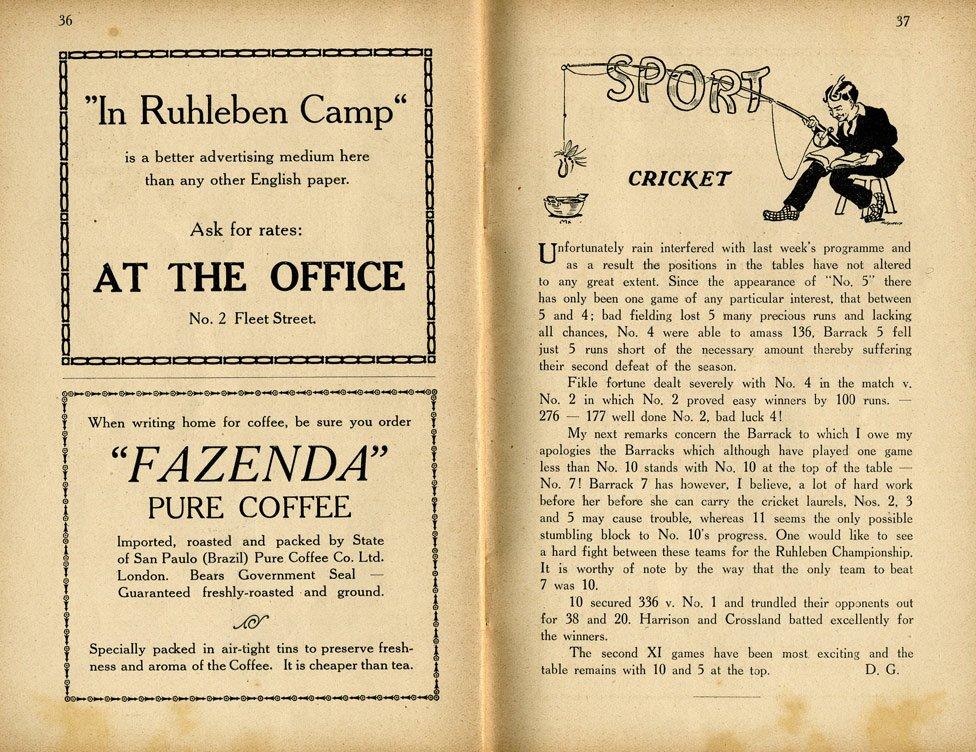

My grandfather was at Ruhleben. Like a lot of the campers, he didn't like to talk about it so we don't know how he came to be there or what it was like. But I understand he made some lifelong friends. Our family has two magazines that were produced by the prisoners at Ruhleben, and looking at them, it's really fascinating how they created a Little Britain at the camp. Trust the Brits!

After the war Harry Walsh became a founding partner of Coopers & Lybrand which became Price Waterhouse Cooper. He became quite wealthy - he and my grandmother had a large house in London. But most of the family fortune was disposed of down the racetrack. He was quite a character, but he died the year before I was born, so I never got to meet him.

Richard Walsh, Eastbourne, UK

Richard Walsh was not permitted to touch the magazines as a little boy

The magazine was one way for the Germans to communicate rules and requests with the prisoners

The magazine is full of adverts for shops and businesses operating inside and outside the camp

The British obsession with class and rank was on display at Ruhleben

The future Nobel laureate James Chadwick is mentioned as a camp science lecturer

The Royal Horticultural Society is planning an exhibition about Ruhleben this autumn and is very keen to hear from people whose relatives were there, particularly if they have diaries and photographs. Please email Fiona Davison at libraryenquirieslondon@rhs.org.uk

Discover more about the World War One Centenary.

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.