World War One: How 250,000 Belgian refugees didn't leave a trace

- Published

The UK was home to 250,000 Belgian refugees during World War One, the largest single influx in the country's history. So why did they vanish with little trace?

Little could have prepared Folkestone for 14 October 1914. The bustling Kent port was used to comings and goings, but not the arrival of 16,000 Belgian refugees in a single day.

Germany had invaded Belgium, forcing them to flee. The exodus had started in August and the refugees continued to arrive almost daily for months, landing at other ports as well, including Tilbury, Margate, Harwich, Dover, Hull and Grimsby.

Official records from the time estimate 250,000 Belgians refugees came to Britain during WW1. In some purpose-built villages they had their own schools, newspapers, shops, hospitals, churches, prisons and police. These areas were considered Belgian territory and run by the Belgian government. They even used the Belgian currency.

Few communities in the UK were unaffected by their arrival, say historians. Most were housed with families across the country and in all four nations.

The 'plucky' Belgians

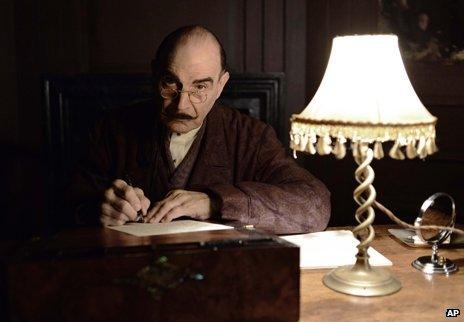

But despite their numbers the only Belgian from the time that people are most likely to know is the fictitious detective Hercule Poirot. Agatha Christie is said to have based the character on a Belgian refugee she met in her home town of Torquay.

There is little else to show they were here apart from a church, some plaques, gravestones, the odd bit of wood carving in public buildings and a few Belgian street names dotted around the country. There is a single monument in London's Victoria Embankment Gardens given in thanks by the Belgian Government.

"It was the largest influx of refugees in British history but it's a story that is almost totally ignored," says Tony Kushner, professor of modern history at the University of Southampton.

This was partly by design. When WW1 finished the British government wanted its soldiers back home and refugees out, he says.

"Britain had an obligation to help refugees during the war but the narrative quickly changed when it ended, the government didn't want foreigners anymore."

Many Belgians had their employment contracts terminated, leaving them with little option but to go home. The government offered free one-way tickets back to Belgium, but only for a limited period. The aim was to get them to leave the country as quickly as possible.

Within 12 months of the war ending more than 90% had returned home, says Kushner. They left as quickly as they came, leaving little time to establish any significant legacy.

"They were pushed out of the country. It wasn't very dignified and the government was happy for the nation to forget. It also suited the Belgium government who needed people to return to rebuild the country."

The few that did stay integrated into British life - many married Britons they had met while in the country.

"They were white and Catholic so they didn't stand out," says Gary Sheffield, professor of war studies at the University of Wolverhampton. "They simply disappeared from view."

The refugees were initially greeted with open arms. The government used their plight to encouraged anti-German sentiment and public support for the war.

"Contact with the Belgian refugees acted as a good reminder of why the First World War was a war worth fighting," says Sheffield.

They were portrayed in the press as "plucky", says Christophe Declercq, who runs the Online Centre for Research on Belgian Refugees and whose great-grandfather was among the arrivals.

"There was a jubilant feeling of going to get 'the Bosche' and the 'plucky little Belgians' fitted into that narrative. It was often the case that if you didn't have a refugee staying with you, you knew someone who did. They were treated rather like pets."

The real Poirot

Poirot is known for his meticulous appearance and brilliant detection skills

First appeared in novel The Mysterious Affair at Styles (1920) and many other subsequent Christie novels until his final appearance in Curtain: Poirot's Last Case (1975)

Poirot novels adapted for the screen have featured well-known actors including Albert Finney, Peter Ustinov and David Suchet

The welcome they received was sometimes overwhelming. One refugee describes in his diary his fright when a scuffle broke out between local people who wanted to carry his luggage for him. There are other stories of thousands of cheering people turning out to greet just a handful of Belgians.

But the goodwill didn't last. Most people expected the war to be over by Christmas but it soon became clear that it wouldn't.

"As Belgians became more permanent guests a lot of individuals and families who enthusiastically housed them ran out of money and/or patience within a few months and returned the refugees to where they had collected them," says Dr Jacqueline Jenkinson, a lecturer in history at the University of Stirling who recently organised a conference on the Belgian refugees.

Housing and jobs became an issue. Belgians in the purpose-built villages had running water and electricity while their British neighbours didn't. More affluent refugees could afford to buy their own properties.

A 'colony' for 6,000 Belgian refugees

Elisabethville was a sovereign Belgian enclave in Birtley, Tyne and Wear

It was named after the Belgian queen

It had its own schools, shops, hospitals, churches and a prison

"Key to the growing resentment was how badly the British were suffering in comparison," says Declercq, who is a lecturer in translation at UCL.

There was also a more personal reason why the refugees slipped from the country's collective memory.

"When British soldiers returned from the war many didn't want to talk about what they'd experienced," says Declercq. "The subject was off limits and as a result their families didn't feel they could talk about what they had experienced at home while the men were fighting, or at least it seemed insignificant. They just didn't have those conversations."

It meant the refugees' story was not remembered at a national level in any significant way or in the homes where they had stayed. WW1 as a whole was a "more complex and problematic" memory for the nation because of issues like the enormous loss of life, says Kushner.

Local exhibitions have looked at the Belgian refugees

Later World War Two broke out and gripped the nation's attention.

"The events of 1939 to 1945 completely overtook the First World War in people's minds," says Sheffield. "There was a new wave of refugees to dominate the memory. So many things about the First World War were forgotten, all the nuances of the subject."

In recent years some local projects have looked into Belgian refugees in certain areas, but the WW1 centenary has also sparked new interest at a national level, as evidenced by last week's academic conference.

"There are the stories out there," says Declercq. "Some families did stay in touch with the Belgians they had looked after and they visited each other for years. We are starting to scratch the surface and find out who these people were."

And his own great-grandfather? After arriving in Britain in August, 1914, he left for the Netherlands at the end of 1915 and settled there.

Discover how wartime Britain coped with the huge number of refugees and more about the World War One Centenary.

You can follow the Magazine on Twitter, external and on Facebook