What goes through a policeman's head before he shoots

- Published

Police in St Louis released a video of their officers shooting a robbery suspect as he held a knife

Police shootings have made headlines in the US this summer. But what really happens before an officer fires his gun?

The circumstances that led to the death of teenager Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, are still unclear. While there is no question that Brown was shot six times by police officer Darren Wilson, there are conflicting stories about circumstance that lead to Wilson pulling the trigger. Was he overzealously shooting at a supplicant Brown, who was unarmed? Or was he defending himself against a violent attack from the 6ft 4in (1.93m) 18 year old?

When it comes to US police officers firing their weapons, the rules - on paper - are very clear.

"Ultimately you come to your firearm as a last resort," says Jim Pasco, executive director of the National Fraternal Order of Police.

"You would only use that weapon in a situation where you felt your life or the lives of civilians in the area were in danger."

A 1982 Supreme Court case found it illegal to shoot at fleeing felons. Now, officers can only justify firing their weapons at civilians if they fear the loss of life or limb.

The advent of Kevlar vests and other protective technologies enable police officers to work with less fear for their lives than in the past.

As a result, the number of killings by police is down 70% in 36 years, says Candace McCoy, a professor of criminal justice at John Jay College in New York. Only a small percentage of the nation's 500,000 police officers are involved in shootings. Most retire without ever firing their gun in the line of duty.

Still, she says, officers are 600 times more likely than a non-officer to kill a citizen, and about 400 people are killed a year by police.

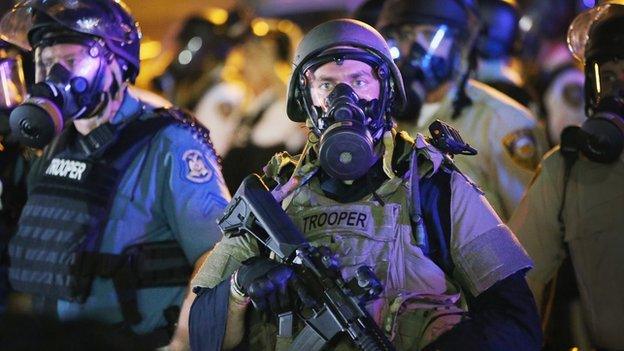

In Ferguson, police have wielded rifles as well as guns that fire rubber bullets and beanbags

While there is no national standard, the state rules and regulations regarding officers' use of deadly force is mostly consistent throughout the country.

Officers are trained on a continuum of force, run through simulations, and are regularly required to recertify in firearms safety,

There are drills and standards and classes. But in the seconds before an officer pulls the trigger, nothing is orderly.

"The officer isn't going through any checklist," says Pasco. "At that point they have to make a split-second decision."

The moment may come after hours of an escalating situation or it might come with little warning.

"You always have to react to a suspect's actions. That's the tough part about it," says Robert Todd Christensen, a use-of-force instructor at Kalamazoo Valley Community College Police Academy in Michigan.

"Cops are always playing the defence, rather than the offense, when it comes to force,"

At that point, the officer has to rely on his training and instincts while trying to control his emotions.

The use-of-force continuum

Officers are trained to escalate force in response to the situation on the ground. Here are examples of that continuum, abridged from guidelines by the National Institute of Justice., external

Officer Presence The mere presence of a law enforcement officer works to deter crime or diffuse a situation. Officers' attitudes are professional and nonthreatening.

Verbalisation Officers issue calm, nonthreatening commands, such as "Let me see your identification." Officers may increase their volume and shorten commands in an attempt to gain compliance.

Empty-Hand Control Officers use bodily force to gain control of a situation, either grabbing and holding a suspect or using punches and kicks..

Less-Lethal Methods Officers use less-lethal technologies to gain control of a situation, such as blunt impact tools like batons or chemicals like tear gas

Lethal Force Officers use lethal weapons to gain control of a situation. Should only be used if a suspect poses a serious threat to the officer or another individual.

"There's an adrenaline that kicks in and there's a split-second syndrome," says McCoy. "Your judgment is not the same as those of us sitting at desks thinking rationally."

Training helps, she says, but it is not perfect.

When law enforcement officials do shoot, they shoot to kill - a measure designed in part to reduce gunplay.

"You hear about 'shoot to wound' by well-meaning people who want to prevent the death of suspects," says Ms McCoy. "That's a very bad idea."

Doing so, she says, would make firing the weapon a less momentous act.

"By saying a police officer must draw the gun only to protect life, you reduce police shootings."

Shooting to wound is also impractical because in the seconds before an officer fires his gun, his or her aim may be anything but true.

"Your heart rate is way up above 200, and you have tunnel vision, you can't even see your sights," says Christensen, referring to the guides on the gun that help locate a target.

"Hit the kneecap? You can't even see a kneecap."

Instead, officers are taught to aim at "centre mass" - the centre of a suspect's chest. That provides a broad target and one most likely to eliminate the threat posed by the suspect. It's also most likely to kill.

Police respond to a shooting in Santa Monica

After a citizen is shot by an officer, that officer becomes the target of an internal inquiry, and can be the investigated by the federal government or other outside agencies.

In the large majority of cases, no charges are brought against the officer.

That is in part because in a case of reality versus perception, the police officer gets the benefit of the doubt.

"Maybe he wasn't in danger, but if he reasonably believes he was, he would be justified in shooting," says McCoy.

That the same benefit of the doubt is not afforded to innocent men shot by the police is the source of much of the tension in Ferguson, even as the actual details of the shooting are still unclear.

But even if charges are never filed, the officer is not totally unburdened.

"Interview a police officer who has shot someone you will get a sad and damaged person," says McCoy.

- Published20 August 2014

- Published20 August 2014

- Published20 August 2014