Arthur Conan Doyle's eerie vision of the future of war

- Published

A century ago Sir Arthur Conan Doyle wrote a short story about the threat of starvation in Britain - caused by enemy submarines - and the need for a Channel Tunnel. Was his bleak vision justified?

He's best remembered for Sherlock Holmes, but 100 years ago Sir Arthur Conan Doyle published a very different kind of story.

"Danger! Being the log of Captain John Sirius" appeared in the July 1914 issue of The Strand magazine. It envisaged Britain being starved into submission by eight enemy submarines. The underwater menace came from the fictional country of Norland but was a thinly veiled reference to Germany's naval power.

The story is told from the point of view of Captain Sirius, a cunning submarine commander in Norland's navy. Britain and Norland are at loggerheads. By rights, tiny Norland should capitulate to British demands. But Sirius convinces his nation's king that there is another way. While British forces occupy Norland's ports, Sirius's eight submarines hunt down merchant shipping heading for Britain. It is a new tactic and one the Royal Navy is powerless to combat. Soon Britain is close to starvation. While Norland, linked to mainland Europe, is still well supplied.

"In the great towns starving crowds clamoured for bread before the municipal offices, and public officials everywhere were attacked and often murdered by frantic mobs, composed largely of desperate women who had seen their infants perish before their eyes," Sirius narrates. In a matter of weeks, the British have agreed to an armistice. Sirius has won, the submarine has arrived.

Other predictive war fiction

1903 novel The Riddle of the Sands, by Robert Erskine Childers, predicted war with Germany in the shape of an imaginary German raid on England, external

The Invasion of 1910, written in 1906 by William Le Queux, was critical of the British government's lack of preparation for a German invasion

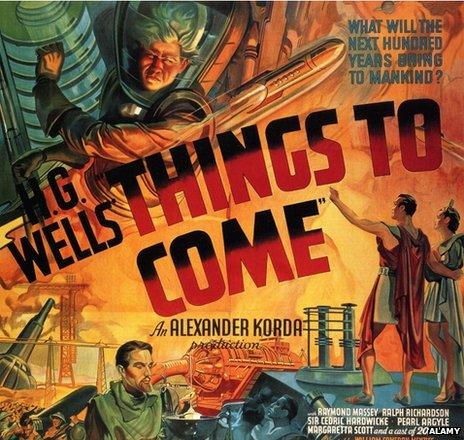

HG Wells' The Shape of Things to Come, published in 1933, predicted a global conflict within a decade, sparked by a conflict between Germany and Poland in January 1940, as well as the use of carpet bombing from the air

The text was designed to shock and alarm readers, and force them to demand action from their leaders. Conan Doyle, through Sirius, apportions blame for Britain's collapse. "The true culprits were those, be they politicians or journalists, who had not the foresight to understand that unless Britain grew her own supplies, or unless by means of a tunnel she had some way of conveying them into the island, all her mighty expenditure upon her army and her fleet was a mere waste of money so long as her antagonists had a few submarines and men who could use them."

The story is long on military detail and short on psychological drama. It is basically propaganda. So did it work?

The Strand published an accompanying piece with a response by naval experts. According to Daniel Stashower's Conan Doyle biography, Teller of Tales, they praised the story's vision. "Sir Arthur Conan Doyle has placed his finger on the neuralgic nerve-centre of the British Empire - ie the precarious arrival of our food supply," wrote Arnold White, a naval historian.

World War One at sea

But there was scepticism to the prediction of outright submarine war. Admiral CC Penrose Fitzgerald wrote: "I do not myself think that any civilized nation will torpedo unarmed and defenceless merchant ships."

Admiral William Hannam Henderson added: "I do not think that territorial waters will be violated, or neutral vessels sunk. Such will be absolutely prohibited, and will only recoil on the heads of the perpetrators."

Another admiral, Sir William Kennedy, attacked Conan Doyle's call for a Channel Tunnel. "God made us an island, by all means let us remain so."

And yet, Conan Doyle, not the admirals was proved right by events, says Duncan Redford, author of Submarine - A Cultural History from the Great War to Nuclear Combat. "As a piece of propaganda it didn't work. The British didn't believe that the enemy would attack non-combatants. But that doesn't mean Conan Doyle wasn't spot on."

Conan Doyle's story predicted that submarines would unleash a new, indiscriminate form of warfare. Merchant ships would be fair game, including those from neutral countries.

Up until then the Prize Rules (also known as Cruiser Rules), meant that warships could stop but not sink merchant shipping. They would check the vessel's cargo. And if they were carrying munitions or supplies for the enemy's war effort they would be taken to port and confiscated.

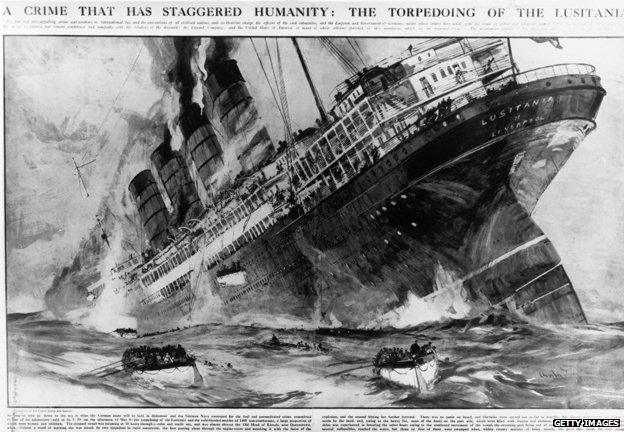

Captain Sirius's strategy proved prophetic. On 18 February 1915 Germany announced that every British merchant ship entering British water would be destroyed. That approach widened to take in neutral ships. In May 1915, the transatlantic liner Lusitania was torpedoed on its way to Britain. Almost 1,200 people died, 128 of them American, causing outrage.

The Germans pointed out that it was carrying munitions for the war but soon modified their policy to attack only British ships. But in February 1917 Germany once again began attacking all merchant ships headed for Britain. "People were extremely worried in April 1917 that Britain would be forced out of the war," says Redford. "There were estimates of only a few weeks' worth of food left."

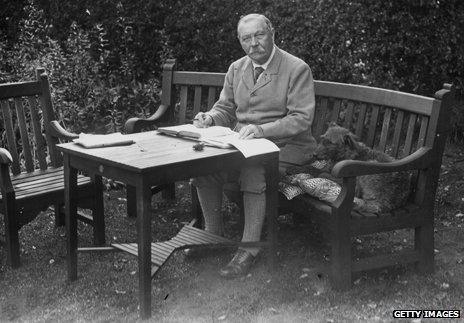

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (1859 - 1930)

Writer, journalist and public figure best remembered as the creator of detective Sherlock Holmes

Born in Edinburgh, he first trained and worked as doctor

Sherlock Holmes made his first appearance in A Study of Scarlet, published in Beeton's Christmas Annual in 1887

Doyle wrote histories of the Boer War and World War One, in which his son, brother and two of his nephews were killed

Twice ran unsuccessfully for parliament - in 1900 and 1906 - and in later life became interested in spiritualism

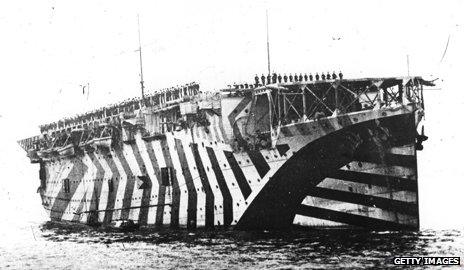

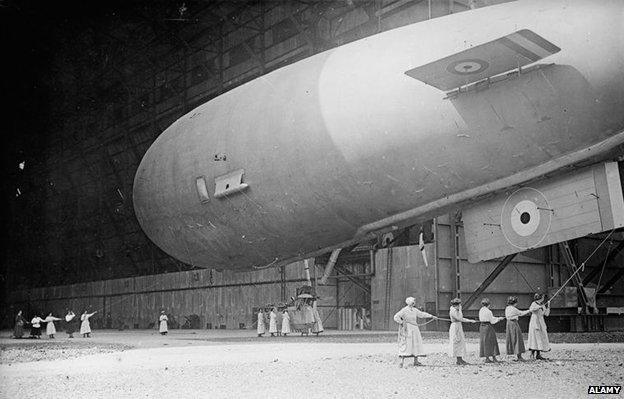

Britain survived by bringing in convoys watched over by airships. But it was a close-run thing.

But far from being applauded, Conan Doyle's far-sightedness rebounded on him. On 18 February 1915, the Times reported that German newspapers were crediting the naval blockade of England to Conan Doyle's story. "We had the idea ready-made for us in England," one source was reported to have said. "Conan Doyle suggested the outlines of a plan which every German has hoped would be used. His story, 'Danger,' will tell you far better than I can what we intend to do."

It is unlikely Conan Doyle really did give the enemy an advantage, Stashower's biography argued. But "as an exercise in demoralising propaganda, however, the episode made perfect sense," he wrote. "If Conan Doyle, one of Britain's most beloved public figures, could be seen to have aided the enemy, it would seem as if Sherlock Holmes himself had betrayed his country."

The point was reiterated in the German parliament in 1917 when the German secretary of the navy said: "The only prophet of the present economic war was the novelist Conan Doyle."

Early in the war Conan Doyle felt he had to make a statement addressing the German propaganda. "I need hardly say that it is very painful for me to think that anything I have written should be turned against my own country," he said.

In the end it was a blockade that helped win World War One. But it was the Royal Navy's blockade of Germany - using mainly warships rather than submarines - that strangled Germany.

At the end of Conan Doyle's story, the narrator quotes from a fictional Times leader, calling for possible remedies. Firstly, Britain, as an island, should become more self-sufficient in food. "The second lesson is the immediate construction of not one but two double-lined railways under the Channel."

In fact, a few weeks after the story's publication, the House of Commons was set to debate the idea of a tunnel. But the day before it was due to take place Archduke Francis Ferdinand of Austria was assassinated in Sarajevo. The debate never took place.

It wasn't until 1994 - 80 years after Conan Doyle's story - that today's Channel Tunnel finally opened.

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.