Should we build just like the Victorians did?

- Published

The Victorians famously built wildly ambitious infrastructure projects, like roads, railways, sewers and tunnels. But should we copy their example, asks David Wighton.

When politicians are trying to persuade the public that Britain should spend billions on a new airport or rail line they often come up with the same argument. "The Victorians would have done it," they declare confidently.

The British must rediscover the boldness and ambition of their Victorian forebears, say the politicians.

But wait a minute. The Victorians certainly built some splendid infrastructure, some of which we are still using today, but when you take a closer look, their record is mixed to say the least. The lessons to be learned from their experience may not be the ones politicians think they are.

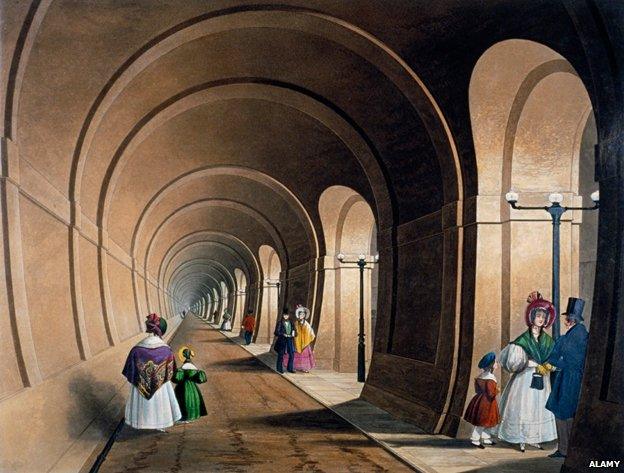

Take Marc Brunel's tunnel under the Thames in London's docklands. The first underwater tunnel anywhere in the world, this was a milestone in civil engineering. It was bold and ambitious - and in many ways a disaster.

It was certainly a disaster for six workers who drowned in one of the many floods that dogged its construction. It was almost a disaster for Marc Brunel's more famous son Isambard Kingdom, who narrowly escaped with his life.

And it was a financial disaster for the investors who backed the project, including the Duke of Wellington, because it ran out of money before the tunnel was completed.

Like many ambitious schemes before and since, it had to be bailed out by the taxpayer. But the government only provided enough money to finish the tunnel itself, not to build the ramps needed for cargo in horse-drawn carts. That left it open only to pedestrians and, instead of becoming a vital new transport artery for the world's biggest port, the desperate promoters had to turn the tunnel into a visitor attraction.

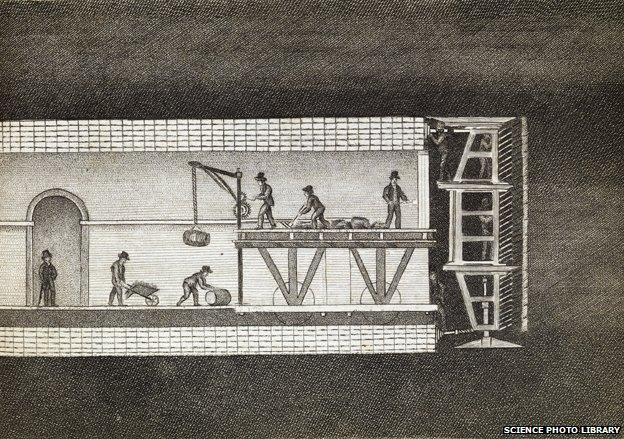

Construction on the Thames tunnel had to stop for eight years because of accidents

"In 1852, they launched the world's first underground fairground. In the tunnels there were sword swallowers, fire-eaters, magicians, tightrope walkers and Mr Green, the celebrated "bottle pantomimic equilibrist".

"A whole section of the tunnel was decorated as a ballroom and they had a steam-powered musical organ. This was the best party in London," says Robert Hulse, director of the Brunel Museum, which is based at the entrance to the tunnel in Rotherhithe.

Eventually, the tunnel became part of the London rail network. But it must go down as both an engineering triumph and as one of the forgotten failures of Victorian infrastructure.

According to some academics, the Victorians have gained an undeserved reputation because only their more successful projects have survived.

One of the lessons often drawn from the Victorian record is that as much as possible should be left to the private companies, which have greater incentive to control costs than the public sector.

Yet there was certainly huge waste during the Victorian era when most projects were carried out by entrepreneurs looking to make a profit.

The railway network is often seen as one of the crowning glories of Victorian infrastructure, but it was deeply flawed, according to Mark Casson, an economics professor at Reading University, and author of the book The World's First Railway System.

Competition between developers and their star engineers, such as Brunel and the Stephensons [Robert and George] led to spiralling costs.

"There was competition… as to who could do the most prestigious and glamorous project," says Prof Casson.

Brunel famously built the entire Great Western Railway on a different gauge from the rest of the system.

"One consequence of this was huge inconveniences, particularly at places like Gloucester, where people had to get off the train accompanied by their luggage and get on to another train merely to complete their journey," says Casson.

Victorian train travel could be slow, especially if you were travelling via Gloucester station

By the 1890s, the costs of the network had pushed fares and freight charges so high that the railway system had become a handicap for the economy, and other countries in Europe, where the state had a greater role, were becoming much more competitive, Casson says.

Similar cost problems were encountered in building the early road network according to Jo Guldi, of Brown University in America, author of Roads to Power.

"When Thomas Telford built the Menai Straits Bridge it was the first suspension bridge in the world and it had to be rebuilt three times."

The Menai Strait bridge - if at first you don't succeed, try, try again

Dieter Helm, an economics professor at Oxford University, believes that the most impressive achievements of the Victorian era were not those projects done by private companies, but the public water and sewage schemes funded by local authorities in cities such as London, Manchester and Birmingham.

But he believes the critics of the railway system are missing the point.

"It is undoubtedly true that, with hindsight, we could have constructed a better railway system. But you always have to have in mind what would have happened if you hadn't done it at all."

The private sector got the railways built quickly, giving Britain a key competitive advantage over its rivals, even if they subsequently caught up.

Bent Flyberg, a professor at Oxford's Said Business School, says it is wrong to assume that if the UK is still using Victorian infrastructure today that proves it must have been a good investment.

He cites a more modern project, the Channel Tunnel, which has been a financial disaster not just for the original investors. "Even for the overall economy it is a loser because it cost more than the benefits that it actually generates for the economy," says Flyberg. He estimates the loss to the UK economy has been $17bn (£10.5bn).

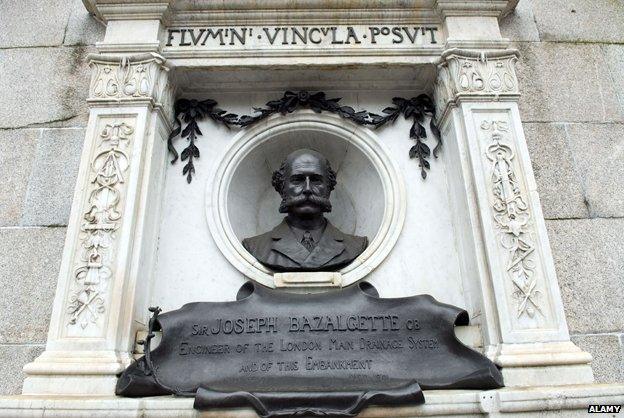

Sir Joseph Bazalgette (1819-1891)

Began career as railway engineer and was appointed chief engineer to London's metropolitan board of works in 1856

At that time London lacked adequate sewage system to cope with increasing population and new flush-toilets. After the hot summer of 1858 created the Great Stink of London, MPs passed legislation to enable new sewage system, overseen by Bazalgette

More than 80 miles of underground brick main sewers and 1,100 miles of street sewers built. Outflows were diverted downstream where they were dumped into the Thames

Scheme involved major pumping stations at Deptford, Crossness, Abbey Mills and Chelsea Embankment

New system was opened by Edward, Prince of Wales in 1865, although the whole project was not actually completed for another 10 years

One of the Victorian schemes that few would dare to criticise is the London sewer network, built by Joseph Bazalgette in the 1860s after growing volumes of sewage in the Thames resulted in the Great Stink. But Andrew Tyrie MP, chairman of the Commons Treasury committee and a former adviser to two chancellors, suggests this is an example of overspending by the Victorians.

"It may be that even some of the apparently most successful Victorian projects from which we are still benefiting were over-specified," he says. "More money was spent on them than needed, and there were a good number of projects which didn't get built because that money was absorbed in over-specified public sector contracts."

Tyrie says that when assessing a potential project it is critical to compare the predicted benefits with other possible uses of resources. Too often this was not done in the Victorian era.

Crossness pumping station - part of Joseph Bazalgette's London sewage network

According to Casson, one of the key problems with the development of the Victorian railways and with many other infrastructure projects was the role of the politicians.

"There is a conflict between politicians seeking popularity and prioritising schemes because that is what the people want, rather than the rational calm and calculated approach to railway construction of the civil servants. I think today we see something of the same."

For Helm, it is clear that society needs to take bold decisions on infrastructure, "while recognising upfront that there are going to be mistakes and there are going to be costs".

But the idea that the Victorian record can be used to justify big schemes today rests on rather shaky foundations.

Build and Be Damned will be broadcast on Tuesday 9 September at 16:00 BST on BBC Radio 4 - or catch up on BBC iPlayer.

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.