My family and other ibex

- Published

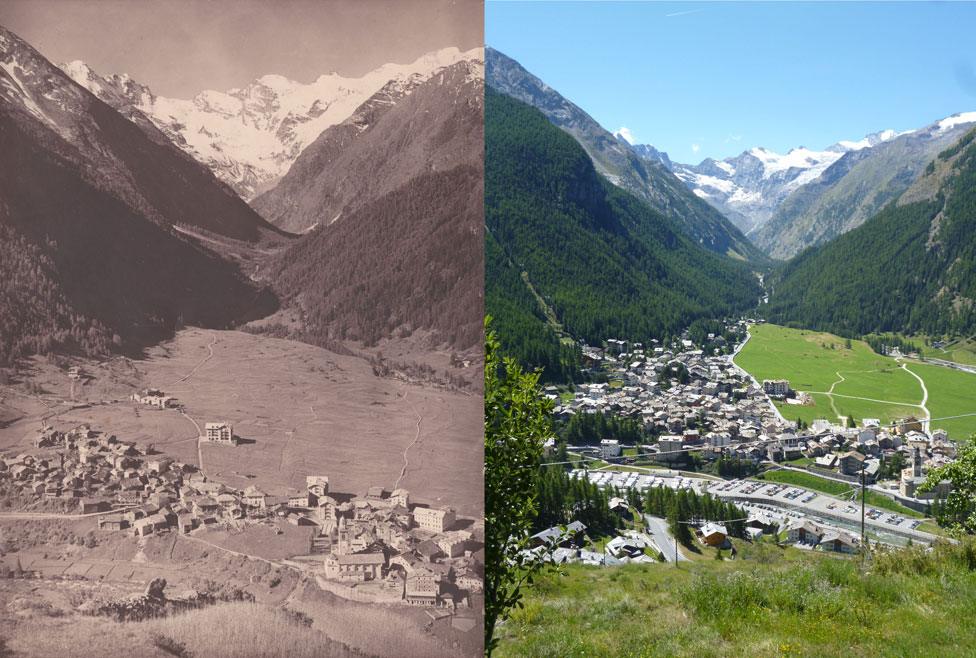

My father's photograph of Cogne, and another taken in 2012

The mountain goats of the Italian Alps used to be encountered by any hiker who ventured high enough. Nowadays you have to work a bit harder. Prof Andrea Sella returned to the area of his childhood holidays to find out why.

It was not far from the treeline that we saw him - a magnificent large male ibex, dark beige and shaggy as he shed his winter coat, sporting a pair of huge curving horns.

Forty years ago, my father took me up this valley in north-west Italy's Gran Paradiso National Park to see these iconic goats. It's a valley where he too spent his summer as a child with his grandmother back in the 1930s and which, judging from an old photograph that sits in his study, has changed remarkably little since. It has none of the hideous towering hotels and the scarred forests of so many Alpine resorts. Instead, the village of Cogne still curls round one side of the huge meadow, the Prato di Sant'Orso, that provides hay for local cows through the winter.

The ibex (Capra ibex) had once been hunted almost to extinction in the Alps, but were saved by a keen hunter, the King of Italy, Victor Emanuel II. In 1856, he set aside a vast hunting reserve where he could unwind from the stresses of political life down in the plains. In 1919, his nephew Victor Emanuel III donated the reserve to the nation, creating the first and largest of Italy's national parks. It was animals from this park that ibex were reintroduced across Europe from Switzerland to Slovenia.

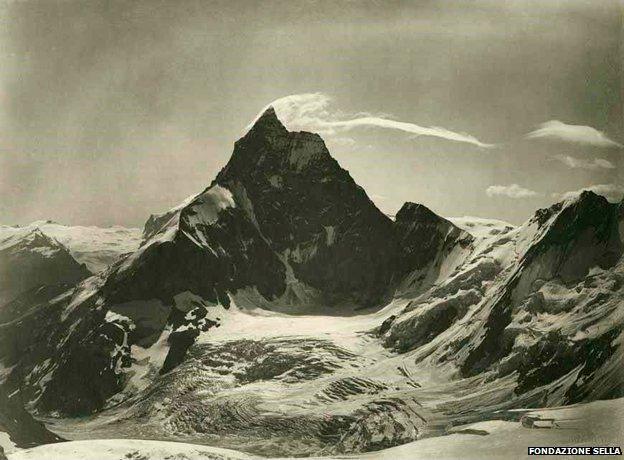

I returned this summer to see how much the valley had changed, not simply since I came as a boy, but since the valley was photographed at the end of the 19th Century by one of the greatest of all mountain photographers, Vittorio Sella. Vittorio, who my family has always assumed to be a distant relation, hiked and climbed across the Alps documenting the mountains in exquisite, luminous detail.

With Dr Achaz von Hardenberg, a park biologist who is an authority on the ibex, I hiked up one of the mule tracks that the king had built 150 years ago. It took us some time to see our first ibex nibbling grass quietly to one side of the path, near the ruins of an abandoned shepherd's hut.

Achaz looked through his binoculars to read the multi-coloured tag hanging from the right ear of the animal. After making a call to park headquarters, he established that this was a 14-year-old male nicknamed "Archimedes", who had been seen a week before in the neighbouring valley and had made the trek over a snow-covered pass well over 3,000m high - thinking perhaps that the grass might be greener on the other side.

Keeping track of animals in the park is a central part of the work done by the park rangers and biologists, who have built up detailed records of the numbers of wild animals in the park going back almost 60 years. These records show something very peculiar.

"The population of ibex rose through the 1980s and 90s, reaching a maximum population in 1993 of almost 5,000 individuals," says Achaz. Through this period the ibex population tracked snowfall very closely - as winters got milder, more animals survived and the population rose.

"After that the population declined steadily until 2009, when we counted only 2,321 individuals -which is lower than we have ever recorded since 1956."

Achaz and his colleagues began looking more closely at the population data. What they found was surprising. While milder winters helped the adult ibex to survive and live longer, things looked very different for newborns. For young kids they found a precipitous decline in the first-year survival rate from 60% in the 1980s to 35% now.

Achaz and his colleagues realised that in addition to getting less snow in winter, the thaw was coming earlier. The melting of snow is accompanied by the sudden growth of tender new grass, the spring "green-up", that should provide ibex mothers and their newborn kids with rich fodder.

"Since the 1980s spring has been coming three weeks earlier," Achaz told me. "Our hypothesis is, external that because we are having the earlier spring, there is a mismatch between the timing of the birth of the kids and the optimum moment when we have the highest quality of the grass." In other words, by the time the female ibex give birth, the grass is already dry and tufty, and much less nutritious.

This effect is not restricted to the Alps, but has also been seen in the Rocky Mountains, where bighorn sheep and mountain goats have suffered similarly complex changes.

Park ranger Marco Grosa, a trim and athletic man in his early 50s, poured us big cups of sweet tea as he talked about other changes he's seen in the park in the 30 years he has worked here - not just the goats, the snow and ice and the timing of the green-up.

From his bookshelf he picked out a guide to the flora of the Alps, and opened it to the entry for Androsace septentrionalis, the pigmy rock jasmine. The description reads "found up to 1,900m (exceptionally to 2,200m)". Moments later we were outside looking at a patch of tiny flowers nestling by the side of the building.

"The altitude here is 2,700m. I don't know how these guys got here," he said.

The next morning, he took us on a quick walk round the area identifying birds by their calls and pointing out dozens of flowers, some well above their normal range. "The valley has changed. I don't know where this is going." he said.

Back in Cogne, I phoned an old family friend who arranged a meeting for me with a couple of elderly mountain guides, Alfredo Abram and Antonio Guichardaz, both now in their 80s. Alfredo had taken me climbing when I was a boy, and to my surprise, he still remembered our time together.

I asked him about the Grivola, a perfect pyramidal peak photographed memorably by Vittorio Sella.

"I first climbed the North face of the Grivola in 1956. We put on our [ice-climbing] crampons when we left the bivouac hut and we didn't take them off until we reached the summit," said Abram.

"When I did it for the last time in 1985 there was no ice, let alone snow. We didn't need crampons at all."

Antonio Guichardaz also talked about enormous changes.

"We grew up with the glaciers on our doorstep. Now it's all loose rock. It's very strange." For both Alfredo and Antonio, the retreat of the glaciers is something both puzzling and worrying, especially as once reliable springs and streams have begun to dry up.

Before I came on this trip, in my mind's eye the Cogne valley had been a bit like one of those little snow globes that you buy in a tourist shop, an isolated world suspended in time, rather like the mountains in Vittorio Sella's photographs. But hearing the guides' and the ranger's incomprehension at the speed and scale of the changes they have seen over their working lives brought home powerfully how even this remote valley is not disconnected from the rest of the world.

They told a story that no visitor on holiday will be even dimly aware of. It is true, of course, the glaciers have been retreating gradually since the last ice age. But the little white flowers that Marco Grosa spotted living so high above their normal range, speak to us of the almost imperceptible warming of our world - and they thrive on the very same slopes where baby ibex go hungry in the spring.

Follow @BBCNewsMagazine, external on Twitter and on Facebook, external