Understanding black America and the spanking debate

- Published

Stacey Patton says her childhood punishments left physical and emotional scars

The NFL football star Adrian Peterson's child abuse scandal has sparked a national debate, external in America about spanking children and the growing illegality of certain kinds of "abusive" corporal punishments. In a personal piece, author Stacey Patton describes the complex legacy of corporal punishment in black America.

As a young child, my adoptive mother stripped me naked and whipped me with switches, belts, hangers, shoes, and extension cords.

She left physical and emotional scars and called her parenting techniques "spankings" or "good butt whoopings."

Her reasons? Because the Bible said it was right, she loved me, she wanted to protect me from the mean streets, drugs, early pregnancy, and white people who she said wanted to beat me up, lock me in a jail or leave me for dead in the streets.

I heard this message everywhere - at family gatherings, in black churches, hair salons and barbershops, on radio stations, and in the performances of countless black comedians.

I ran away at age 12 and bounced around in foster care before landing a scholarship to boarding school.

Driven to understand why my adoptive mother and most black people believed so strongly in physical discipline, I earned a PhD in African American history and wrote a memoir about the historical roots of corporal punishment in black families and the intersections of race and parenting in modern times.

.jpg)

Peterson has been indefinitely suspended by the Vikings for child endangerment

The Peterson controversy spotlights the struggle between the black community's deeply rooted attachment to spanking and laws that criminalise a disproportionate number, external of black parents for that behaviour.

Corporal punishment is deeply embedded in Christianity and Western culture, and in African-American culture it is related to slavery and Jim Crow segregation. Slavery and post-emancipation racial terrorism may be part of our story, but it is not the whole story.

Too often discussions on race and harsh parenting techniques are essentialised as pathologically black or black poor, even though the practise is more variegated by class and religion.

America is a nation where 90% of all parents across racial and ethnic groups use corporal punishment at some point, but there's a prickly cultural divide, external between blacks and whites on what is deemed appropriate.

Many blacks are defending, external Peterson with arguments that "a good whooping" is love and not abuse, and that it keeps children in line and hopefully safe from the wrath of the police or the prison system.

Studies show that black parents are more likely, external to use corporal punishment than any other group. Why?

Historically the black body has been subject to racial control, through centuries of slavery, lynching, sexual violence, reproductive legislation, surveillance, segregation, mass incarceration, police practices, and popular entertainment.

Black parents have responded to this systemic violence by debasing their children through harsh physical punishment. But few parents view spanking through this lens. It has simply been considered by most to be a core feature of black identity, quality parenting and responsible citizenship.

Underlying black parents' attachment to spanking is a very real fear, based on black suffering and random violence at the hands of white people.

Blacks are quick to defend the need to spank and feel misunderstood when criticised in a society where the consequences for stepping out of line are much harsher for black children than white ones.

When former professional basketball player Charles Barkley, external said that "I'm from the South. Whipping - we do that all the time. Every black parent in the South is going to be in jail under those circumstances," he accurately represented the historical black perspective on parenting throughout the US.

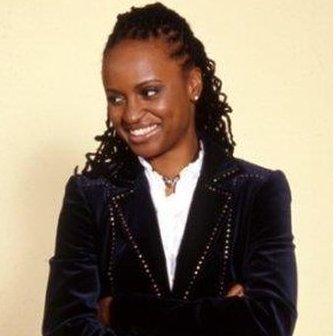

Stacey Patton is the author of a book on the historical roots of corporal punishment in black culture

In fact, whipping children has long been a badge of cultural superiority and morality in black communities.

Many black parents identify the refusal to spank as "white," viewing white parents as too permissive and not in proper control of their children, especially in public spaces.

The Peterson controversy exemplifies how this tradition of harsh discipline is clashing with growing anti-child-abuse laws that punish parents.

Though corporal punishment is still legal in public schools, external in 19 American states, sentiment is shifting in favour of non-physical methods of discipline. This sentiment is informed by 50 years of scientific research on the negative impact, external that hitting has on children's developing bodies, external and brains.

One question is whether these anti-spanking laws and white people's righteous indignation over harsh black parenting expose an agenda beyond a genuine effort to protect children.

Since black parents are most likely to spank, these laws put them at greater risk for arrest, thus feeding the incarceration pipeline. And since most black families are headed by single parents, a parent's arrest often sends their children into foster care, which also feeds the juvenile justice and adult prison pipeline.

What is striking to me is that white America seems very comfortable with teachers, principals, police officers, prison guards and neighbourhood watchman brutalising black bodies, but criminalises black parents for doing the same.

One would hope that we can repel and denounce all efforts to portray violence as a means to discipline and punish.

The controversy and cultural clashes around the Peterson case are signs of a society in the process of reconsidering long-accepted traditions and practises.

Whatever happens to Adrian Peterson, this issue is a sleeping giant that has awakened and can no longer be ignored.

Stacey Patton is a senior enterprise reporter for the Chronicle of Higher Education and the author of the book That Mean Old Yesterday.