The companies vying to turn asteroids into filling stations

- Published

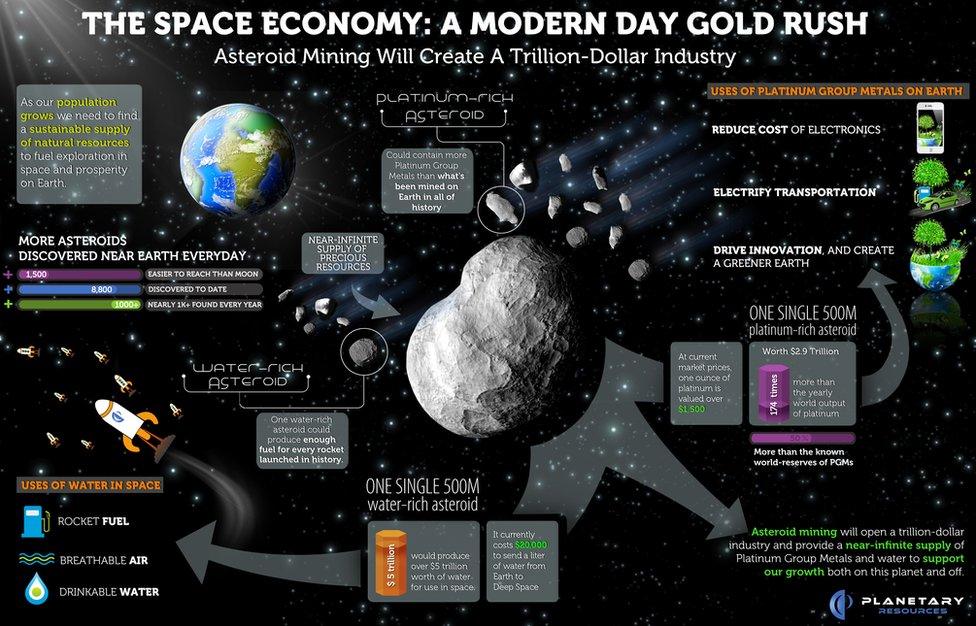

Private companies want to mine asteroids for fuel, and build filling stations in space. A bill now in front of the US Congress would help by allowing them to own what they discover - but it might, if passed, meet stiff international opposition.

Chris Lewicki is trying to get water from a stone. A really big stone thousands of miles from Earth.

The president of space mining firm Planetary Resources used to oversee robotic Mars missions at Nasa, but today he's betting big on asteroids.

The chunks of matter hurtling through the cosmos are rich in valuable minerals, he says, but finding water could be like striking liquid gold.

"We can tell from telescopes that look out from mountaintops here on Earth that certain types of asteroids can be relatively abundant in water and water-bearing minerals," he says.

But why is water, which covers much of our planet, so valuable in space?

According to Lewicki, it currently costs nearly $2bn (£1.2bn) per year to launch enough water - six tons per person - to sustain the six astronauts aboard the International Space Station.

But, in addition to providing drinking water, H20 can also be converted into breathable air, and into fuel - liquid hydrogen and oxygen form the most efficient rocket fuel known to man.

Currently, spacecraft must carry all the fuel they require, adding significant weight and driving up the cost of getting beyond Earth's gravity. Once in space, expensive equipment may be abandoned because it's too costly to take back to Earth.

But, says Lewicki, "Imagine being able to get into space and refuel your spaceship [there]."

Asteroids have little gravity, he adds, so landing on and taking off from them does not require too much energy. Their prevalence and proximity to Earth make them valuable potential way stations for refuelling on longer missions into space.

Michael Lopez-Alegria, former Nasa astronaut and current president of the Commercial Spaceflight Federation, says industry is definitely interested in the "very lucrative" idea of space mining, and not just on asteroids.

"There's an amazing amount of frozen water at the polar regions of the moon," Lopez-Alegria adds. "The moon is easier to get to than an asteroid, it's right next door and it's much easier to communicate with a robot or people [there]."

Unfortunately, strict legislation in the form of the 1966 United Nations' Outer Space Treaty, external already prohibits national appropriation of space resources. Basically, mining the moon is legally off limits.

But, experts say mining asteroids - particularly for resources which could remain in space - falls into a legal grey area unconceived of by legislators four decades ago.

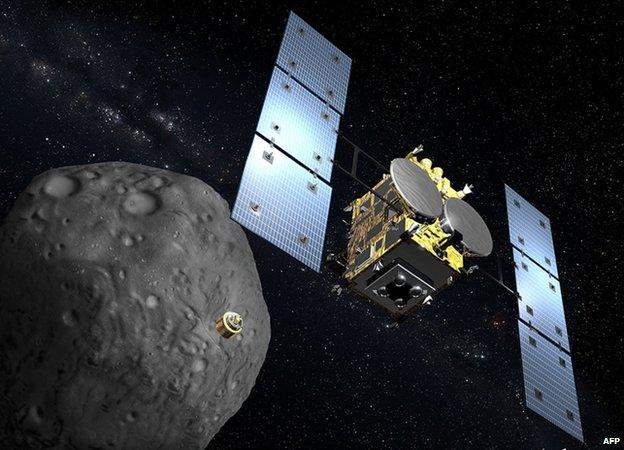

A graphic shows Japan's planned launch of Hayabusa-2 to retrieve samples from asteroid 1999 JU3

As the commercial space industry grows, with billions of dollars already invested, entrepreneurs argue they should be able to own what they find. The costs are simply too great to risk having their discoveries taken from them by governments or competitors.

Lewicki says the lack of legal certainty over ownership is already giving potential investors pause and hurting his company's growth.

Other private companies aren't the only competition, either. Lewicki says China has launched unmanned exploratory missions to asteroids as well as the moon, and Nasa is working on a manned mission to collect samples from a near-Earth asteroid in the 2020s.

If the US wants its private space industry to jump into the fray, argues Lopez-Alegria, legislators must create a more "predictable environment" in which companies can "enjoy the rights of their extraction or to extract without interference" in space.

Cue the American Space Technology for Exploring Resource Opportunities in Deep Space (ASTEROIDS) Act, external, introduced by Republican Congressman Bill Posey in July.

The slim five-page document proposes allowing US commercial entities ownership over "any resources obtained in outer space from an asteroid".

Lewicki gave Posey advice on the bill, and though some people say it is overly vague, he argues it provides a broad outline for a new and burgeoning industry.

Democratic Congresswoman Donna Edwards, the ranking member of the US House Subcommittee on Space, disagrees.

In her view, it's perilous to rush into such long-lasting and far-reaching legislation.

"Our job is not to do things, enact legislation, for particular business interests," she says. "Our job is to figure out a plan and a protocol for the United States space program and for the way that we interact internationally."

In a recent Congressional hearing on the matter, space law professor Joanne Gabrynowicz warned the Asteroids Act's potential political impact on international treaties "is likely to be sizeable".

"If made into law, it should be expected that there would be both legal and political challenges to its terms," she added.

The business view of asteroids

Edwards says international partners - including the European Space Agency and Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency - as well as China and Russia, need to be involved from the beginning in conversations over space ownership rights.

"We have to [recognise] that we're not the only game in town," she says. "We have an obligation... to figure out what the lay of the land is going to look like and all of us then playing by the same rules."

Ultimately, Edwards adds, "we're not going to be mining asteroids tomorrow, so we have time to figure out what the framework should be".

But, Lewicki says Planetary Resources will be launching its first spacecraft by the beginning of next year and already has plans for several more.

"If Congress finds a way to... bring [space mining] into law, that allows us really to potentially accelerate our efforts and pursue this even more aggressively than we are today," he says.

It's "going to happen much sooner than I think a lot of people realise," Lewicki insists.

"We're not decades away... there's companies ready to do this now."

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.